If you were to define the relationship between Turkey and NATO with a Facebook status, argues analyst Bruno Lété, you would have to opt for "It's complicated."

The worsening in recent years of the links between the Eurasian country and the rest of the members of the Atlantic Alliance is due to an increase in mistrust on both sides.

On the one hand, the support of the United States and several European countries for groups considered by Ankara as terrorists or what Turkey sees as an alignment in favor of Greece in the eastern Mediterranean weighs heavily.

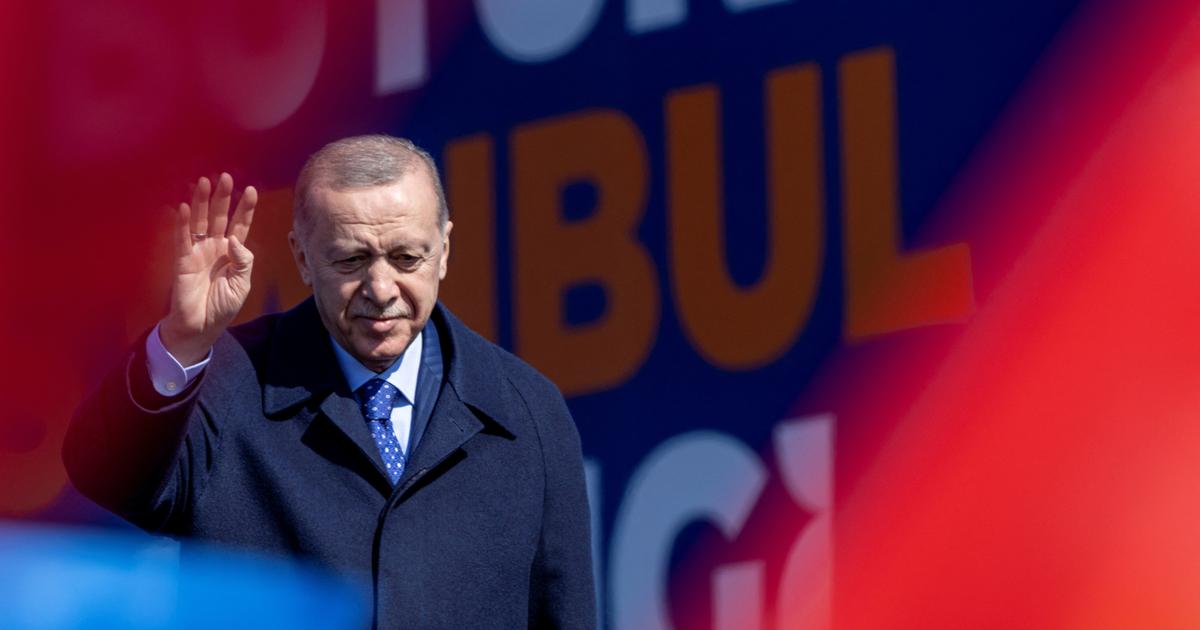

On the other, a Turkish position regarding Russia perceived as ambiguous or the invectives of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan against rulers of allied countries.

In Brussels, headquarters of NATO, debates have resurfaced as a result of the Turkish veto of the accession of Sweden and Finland, explains this security and defense expert from the

German Marshall Fund

think tank .

“Turkey has been a great ally in the conflict in Ukraine.

It has been very active in its support for Ukraine and shares the Alliance's interest that the Black Sea not become a Russian lake.

However, on the question of the entry of Finland and Sweden into NATO, Turkey stands alone, because it is something that the rest of the allies have welcomed”, he affirms.

"And this has revived debates that are not new, but have gained strength again: Is Turkey a bridge or a wall for the Alliance?" he adds.

More information

Last minute of the war in Ukraine, live

There have even been congressmen, retired senior public officials and columnists - mainly in the United States - who have called repeatedly since 2016 to kick Turkey out of NATO, although the Alliance's treaties do not include any clause that provides for the expulsion of its members. or how to do it.

When EL PAÍS asked Ibrahim Kalin, senior adviser to the Turkish president, about this debate, he let out a weary laugh, while lamenting the "misrepresentation" of the situation and the double standards applied to his country.

"We have not been the ones who have questioned the validity of NATO, as other leaders have done [referring to the Frenchman Emmanuel Macron]," Kalin complained, immediately mentioning the case of Greece: "It blocked entry for 11 years from North Macedonia to NATO, not because of a territorial dispute or because of a terrorism problem, but because of a problem with the name of the country.

Did someone say that Greece is not a loyal member of the Alliance or that it was weakening NATO?” Erdogan's right-hand man asked.

Turkey sincerely believes that its partners are failing it.

Brussels believes, also sincerely, that Turkey is consciously playing with ambiguity.

Both sides have every reason to maintain their positions, and it is difficult to purge what is factual from what are mere subjective impressions.

Building bridges with Putin

In the case of Russia, many European governments are concerned that President Erdogan appears to feel much more comfortable dealing with President Vladimir Putin than with the leaders of allied countries, whom he routinely attacks verbally.

They are also suspicious that he has bought a Russian S-400 missile system — and is insisting on acquiring a second — despite warnings of incompatibility with the Alliance's defensive mechanisms.

And that it refuses to apply sanctions to Russia, something that the rest of NATO members have done, and has welcomed Russian money.

Ankara claims that it cannot break the bridges with Moscow to keep open the possibility of negotiating.

Ukrainian diplomatic sources claim to understand Turkey's position.

On the other hand, the support given by the United States to the Kurdish-Syrian YPG militias, closely linked to the Kurdish armed group PKK, which attacks Turkey and which Washington considers a terrorist group, is especially stinging.

Despite the fact that the European Union shares this definition, demonstrations in support of the PKK are seen in various capitals of the continent and its militants raise funds: according to German espionage, between 13 and 25 million euros a year in Germany alone.

But it is equally true that Turkey uses the label of terrorist lightly and that among the individuals whose extradition has been requested there are writers, politicians and journalists who in no European court could be convicted of the crimes they are accused of in their country.

In Turkish society itself, there is a growing mistrust of NATO and the United States, which is linked —as in other parts of southern Europe— with historical roots (such as Washington's support for the coups of the last century), but also with the development of conflicts in the region during the last two decades.

More serious, perhaps, is that this distrust has been igniting for some time with some force in the military establishment, which was Turkey's Atlanticist bastion, and among whose officers ideas favorable to Eurasianism (which seeks alliances with China and Russia) have germinated.

"Turkey and NATO need each other and have common interests, but in several aspects, especially in the Middle East, their interests differ," maintains analyst Lété.

Reconciliation must necessarily happen, argues Turkish defense analyst Ömer Özkizilcik, through a change in US policy in northern Syria: "Working with Kurdish-Syrians who are not affiliated with the PKK and with Arab tribes, actors who could be acceptable to Turkey and to NATO members.”

The issue, he exemplifies, is that “if there is a debate on Turkish television between a pro-NATO analyst and another Eurasianist, and the latter mentions US support for [the Syrian-Kurdish militias of the] YPG, the debate is over.

The Eurasianist wins it.

And this influences public opinion.”

There are those who do not consider it possible to adjust the interests of both sides.

Analyst Aaron Stein warns that even if the Sweden-Finland issue is resolved, "differences between Turkey and NATO will persist."

"The best path for the United States and Europe is to admit that relations with Ankara are transactional and driven by the interests of each one and that they require a constant management effort," he writes on the specialized website

War on the Rocks.

On the other hand, others, such as the former Turkish ambassador Namik Tan, criticize that this way of negotiating by the Erdogan government, even though it is right in its demands, undermines Turkey's credibility.

“Being part of the political, economic and social infrastructure of the West strengthens Turkey substantially.

And for this reason it is of great importance for our national interests to act in harmony with the allies and continue to contribute to the Alliance, ”he writes in the Yetkin Report

digital medium

.

“If we forget this, we cannot be considered a predictable, responsible and reliable ally”, concludes the diplomat.

Follow all the international information on

and

, or in

our weekly newsletter

.

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/KP44QIARGNGUAB7LXEFNMTVFF4.jpg)