Manuel Patrocinio stops, little by little, the recitation of one of his poems.

His voice is like an earth tremor.

The heavy breathing, the livid skin, the rictus of terror.

Everything turns around.

His heart beats faster.

He leans his body on the table, puts a hand to his head and narrows his eyes.

—I feel… —he stammers, falls silent and continues—: I have dizziness.

—Juan, run, run… It's my dad!

He gave her something,” María del Socorro, her eldest daughter, shouts nervously.

"Breathe, take a breath," asks Carmen Alicia, another of her daughters.

It's half past eleven in the morning and the air is suffocating.

In the corridor, little birds twitter locked in small cages.

There are flower pots hanging from the fiber cement ceiling.

In the patio there are more plants, bushes and flowers.

The leaves do not move and the sun is reverberant, implacable.

An intense summer that never ends.

Juan Manuel, his doctor son, takes his blood pressure.

She's low, she exclaims, and orders that they buy her a physiological saline immediately.

When she tries to come to, Manuel Patrocinio tries to sing the Baranoa anthem, composed by him.

In 1992, the municipal symbols contest was won with the lyrics of the anthem;

two of the twelve stanzas were dedicated to Juan José Nieto Gil, the only Afro-descendant president of Colombia who, in an act of racism and exclusion, was erased from history.

Nieto Gil, president in 1861, was a native of this town.

His son Juan Manuel explains that the emotion of reciting caused him to faint.

Some time ago, they had detected a cardiac arrhythmia that it was better not to operate on.

Putting him through surgery at his age was very risky.

When he hears it, with that now dull voice, without verve, he says: "He's ranting."

Then the children take it to the room.

Shortly after, Manuel Patrocinio is lucid again: “Where is the girl?” he asks.

It has survived the wars in Colombia and the pandemic.

He was hospitalized for Covid, but he got over it.

He doesn't take pills, he walks without a cane and he knows dozens of poems by heart.

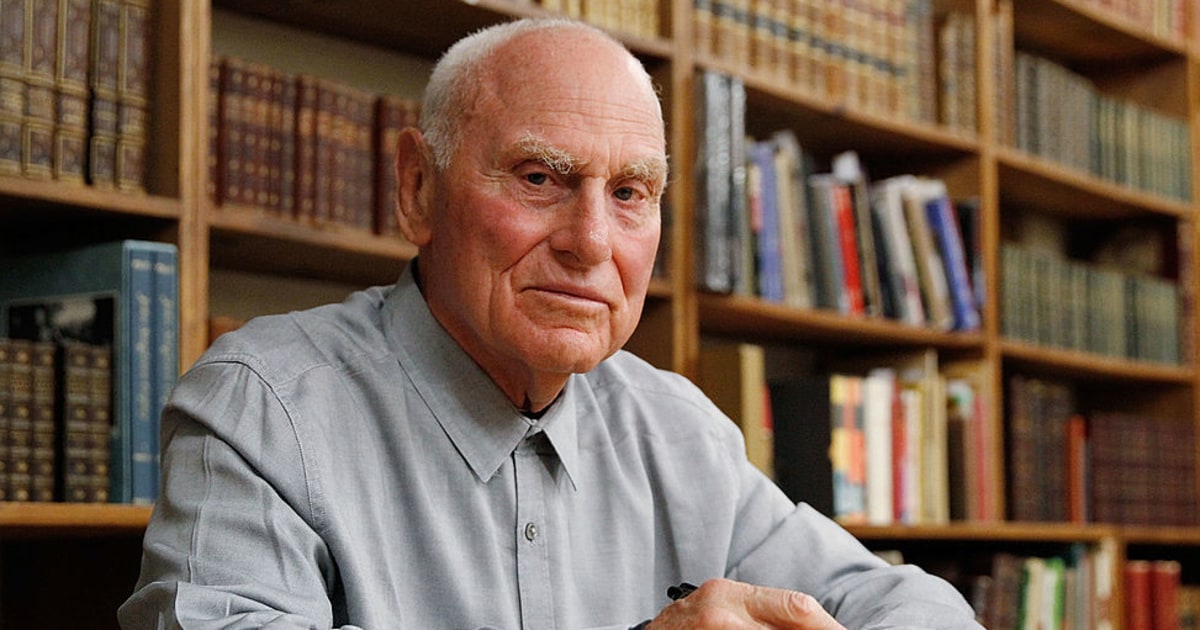

Manuel Patrocinio Algarín Palma was born in 1917 in Baranoa, an hour from Barranquilla, capital of the Atlantic, in northern Colombia.

His face—brown freckles, sunken cheeks—believe a man who has lived so long.

The 104 years are not noticeable in his slightly rough skin, nor in his abundant white hair, like his eyebrows.

His poetry boils in his blood, slips through the cracks of his house, shakes his memory.

“It's an immeasurable passion”, his eyes shine when he says it.

He is not a famous poet, but he is popular in Baranoa and that is enough for him.

He prophet in his town, like few others.

He declaims seriously.

He looks around him, as if he is in front of a large audience.

Shocked, he extends or shakes his hands, lengthening the words, imprinting them with cadence.

"When I dream of you in my arms / and that your soft hands start to caress me / the sorrows they cause me go away step by step...".

He writes poems, Alexandrian verses, sonnets and acrostics.

His style is romantic.

He does not conceive of poetry without rhyme.

He has written to love, to the work of the peasant, to the fishermen.

At the time, to the victims, to the friends who left, to Caribbean poets like Meira Delmar and even to fifteen-year-olds and beauty queens.

You have to speak loudly to him because he has lost his hearing.

Carmen Alicia, her daughter, says that Manuel Patrocinio refuses to use hearing aids.

"I haven't seen the need to use them yet," he clarifies.

—What inspires you the most?

—Everything inspires me: a painful painting inspires me, a happy painting, a rainy sunset, a clear sunset with traces of redness.

Everything inspires me: pain, joy, sadness.

Don Patro, as he is nicknamed in the town, still remembers the names of the streets, when they were not identified by numbers but by names.

At that time there was no electricity or aqueduct.

The youngest of eight children, he grew up in a bahareque and straw house, surrounded by vegetation and a cool breeze.

He opposed his fate as a peasant.

Since he was a child he helped his father in the fields: he planted zaragoza, beans, cotton.

His father, in addition to being a farmer, sold hats and offered games of chance at the patron saint festivities of neighboring towns.

The first trip to Barranquilla, he remembers, was with him, on the back of a donkey, on a dusty road.

They left at 11:30 at night, illuminated by the moon, and arrived exhausted at six in the morning.

—Despite being the youngest of the house, my dad wanted to keep me enslaved in the fields, until one day my mom got mad at him and told him: “He's not going to the mountains anymore, he's going to school.

If you don't take it, I take it."

Manuel Patrocinio studied until fourth grade, when he was the highest grade in school.

He was 18 years old.

Professor Rubén Rolong was the one who discovered his talent as a poet.

—He would take us to the fields, for walks, and then he would make us write down our impressions;

that was the way to teach.

One day she told me: “I see that you are into poetry.

Dedicate yourself.”

Some of the books published by the poet. DIANA LÓPEZ ZULETA

Together with his mentor, he founded a newspaper, El Saturno, which began to circulate weekly.

There he published his first poem,

Clear Summer Nights

, in 1935. Little by little he polished himself.

He became a disciplined reader: from the teachings of Greek philosophers such as Socrates and Plato, to authors such as Julio Flórez, Guillermo Valencia, Cervantes Saavedra, Quevedo, Rubén Darío.

From them he learned the classical vocabulary that permeates his work.

He does not like the use of prose, for him very direct, by García Márquez.

"He has a very personal training in literature based on the aesthetics of language (...), that is why he is not an admirer of the work of García Márquez", says the historian Néstor Zurita in the book

Manuel Patrocinio Algarín Palma, poet and referent of

the

story

The episode that has most impressed him in the country is the death of the liberal leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, in 1948, whose assassination in Bogotá gave rise to violent popular protests.

Manuel Patrocinio prides himself on being liberal.

Poetry has given him the greatest delights, but, like many poets, he has not been able to make a living from art.

He worked in town halls, hospitals and courts of different towns.

He became mayor in charge of Baranoa and fiscal auditor in the Office of the Comptroller of the Republic, in Barranquilla.

His retention, so prodigious of him, could give her the pleasure of doing accounts without a calculator and memorizing the judicial codes and pronouncing them.

He retired in 1988, after working for 40 years.

-He is correct in his things, honest and always willing to serve, that is why he was able to ascend to those positions.

When I was in my second year of high school, he made me read

The Iliad

, but I had to read it in verse, then The Odyssey and The Divine Comedy.

He wouldn't give me money if I didn't tell him about it,” says Juan Manuel, his doctor's son.

Although he had been writing since he was a teenager, his first book,

Autumn Leaves,

was published in 1995, when he was 77 years old.

It was sponsored by the Government of the Atlantic.

From then on, others such as

Luces de mi ocaso and Manantial de acrosticos

followed , which he printed independently, without publishers involved;

he sold them himself.

With five children to feed and a fever overwhelmed by lyrics, he would get up at four in the morning to write and then go to the office.

She wrote the poems in his own handwriting and, when she finished, she passed the text clean on her Olivetti typewriter.

She shared them with her niece Liliana Devis Algarín.

—He would go home and tell me: “I found a new word” or “Look at what I wrote, to see how you hear it”.

And she liked that he listened to him so that he could correct her, of course he was almost always right,” Liliana says with a laugh.

He is a person who unites, summons.

He is an icon, not only in his generation, but among young people and children.

Even today, he attends professors and students who come to consult him on history or literature at home.

The town square is named after him.

A speech of his was not lacking in the civic acts of the schools or the commemorations of Baranoa.

He improvised verses.

***

In his study there is a large wooden desk, a fan, a 1971 model Olivetti typewriter, handwriting, the framed Baranoa anthem, and a painting by Juan José Nieto.

Acknowledgments of all kinds hang on the wall: Honoris Causa, a decoration from the Congress of the Republic, a medal from the Council of Barranquilla, honorable mentions, a glass plaque...

In 1954, he married Carmen Elena Blanco, now 96. Between courtship and courtship, between letter and letter, love lasted 15 years, until she said yes.

They had five children.

"Not only the most beautiful, but the best thing that has happened to me in life, is having found the wife that God gave me."

“She was a discreet young woman with jet-black hair / with large eyes and serene gaze / Spellbound by her / I followed in her footsteps / determined and willing to conquer her love”.

In 1994, at the age of 77, he won, in Santa Marta, the first national position in Poetry and Declamation with

The Night of the Stolen Kiss

, which he dedicated to his wife, then in love, in the 1940s.

“I told him looking at the sky/ Pretty star, don't you see it?/ and when I extended my gaze/ to the sidereal region/ I brought my burning lips/ with the desire to kiss”.

Manuel Patrocinio was only in Bogotá once, but he soon returned frightened by the cold.

His life has always been in Baranoa, a municipality with around sixty thousand inhabitants.

Since the pandemic began, his children do not allow him to go out alone.

He walks on the old floor of the house with geometric figures, goes out to the terrace to get some air —perhaps being calm is the secret of longevity—, sits in a rocking chair, talks with her wife, holding her hand.

At times they look like turtledoves.

She is now in a wheelchair and with health problems.

He used to get up in the morning to sweep the patio, but for fear of falling, now they prevent him from doing so.

He does mental exercises.

Moving his fingers, he lists the syllables of the sonnets.

"Don't think I'm talking to myself," he warns.

He no longer reads, as his near vision has deteriorated, but he watches documentaries and listens to lectures on philosophy, semantics, or literature.

"It's another way of reading," explains Carmen Alicia.

The poet is 104 years old and published his first book at 77. DIANA LÓPEZ ZULETA

In the studio, Carmen shows some photos: reciting poetry in the middle of the square, dressed as a fox at the Carnival of Remembrance or posing with an honorary diploma.

Manuel Patrocinio directed La Loa de los Santos Reyes, a religious play whose tradition, coming from Spain, is more than 100 years old.

He was also an actor and librettist.

He is a lover of music, revelry, carnival and dance.

Until before the pandemic, she managed to escape from the house.

Not that she had to ask permission, but because of her age, being in a riot is dangerous.

Four years ago, when she was already 100 years old, she was having breakfast with the family.

On the village station they announced the death of someone.

“Oh, cousin brother of mine.

I have to offer my condolences”, exclaimed Manuel Patrocinio.

It was Shrove Tuesday.

He dressed up and got on a motorcycle for Galapa, half an hour from town.

He left alone, holding his hands behind him, on the rack of the bike.

He drank alcohol and danced to the sound of drums until the next day, Ash Wednesday.

Another day of carnival, this time in Baranoa, he had previously had a costume made.

He knew that if he told of his plans to go out in a parade they wouldn't let him go.

So, he put the costume in a bag, went to the patio and threw it into the street, through the wall.

"Daddy, where are you going?" Carmen asked him.

"Here, to the store," she replied.

She went to a friend's house, put on her outfit and left.

"Look no further, Don Patro is dancing in the street," a countryman told his worried daughter.

Last November, Manuel Patrocinio turned 104 years old.

His sons serenaded him.

He danced, with one of his granddaughters, to the rhythm of an orchestra with trumpets, saxophones and clarinet.

In a video it was recorded how he moves his hips and takes dance steps with his mask on.

It is pure joy.

—He's the best dancer I've ever had, but he's already getting agitated.

He is an inveterate flirt, in love —says Carmen, his daughter, with a hilarious laugh.

"Couples fight me because I let myself go," says Manuel Patrocino.

—What is the secret to having eternal youth?

—The secret is… I would say that taking care of yourself, not only your health, I am talking about taking care of yourself as a person, because a sick material structure is incapable of producing, so that for the spiritual structure to be able to produce, it has to have its material structure in order. form.

***

One of the few remaining friends of his generation believes that Manuel Patrocinio is dead.

David Gómez Durán turned 106 years old.

Stretched out in his rocking chair, he speaks slowly, as if each word were a piece.

At his age he is still flirtatious, he blows kisses at girls.

He spoke loudly to her, like to Don Patro.

“Great friend of mine.

When we met it was a sweetness, a honey.

We went partying.

An extremely intelligent guy.

He showed affection, friendship —he says.

"How long has it been since you saw him?"

-When he died.

"But he's not dead."

Do you appreciate it very much?

"As if he were alive."

***

The day after the fainting, Manuel Patrocinio is more talkative.

Carmen Alicia has asked not to ask too many questions, to let him rest.

It is a warm afternoon.

He is sitting in a rocking chair on the terrace.

He wears a polo shirt, shorts, leather shoes;

always impeccably dressed.

With a modulated voice and histrionic gestures, this time he recites a poem that he composed for his eldest daughter, written 64 years ago.

I make a move to interrupt him, but he continues with the intonation.

"Don't declaim so much so you can recover," I tell him as soon as he finishes.

-Why?

If I'm not sick,” she says, frowning.

"You need to get some rest."

—On the contrary, if I don't exercise I get worse.

As he speaks, the music of an ice cream cart and the loud beep of motorcycle taxis, the main transport in town, can be heard.

A woman, with a child in her arms, passes dodging the sun with an umbrella.

Every house has a bush at the front door, but the uneven sidewalks are so narrow that people walk on the main road.

"Let's go to the patio, it's cooler," her daughter offers.

Manuel Patrocinio gets up and walks quickly.

Carmen tries to take him by the arm, but he refuses.

"They shouldn't have called him Manuel Patrocinio but Manuel Desperation, because he's desperate for everything," says his daughter with marked irony.

When I approach to take pictures of him, he warns me:

"Am I combed?"

-Yes.

I want to take some pictures of you.

"But I haven't shaved, doesn't it matter?"

Although he grew up in the Caribbean, no dirty word comes from his lips.

He repeats things that she has mentioned, but remains clear and consistent in everything he says.

"Do you know what value implies?"

have love

And when you have love you go to the sacrifice.

The man who is not capable of sacrificing himself for his neighbor lacks value for me.

It's not the physical, it's the treatment of him.

Serve in a timely manner, especially in the needs, that is where the value of the person is, not because he has money, nor because he is nice, nor does he dress well, but because of his feelings.

—Did you like the time before or the time now?

—Before, because of the tranquility, the people were more peaceful, there was more space, not from the cultural point of view, but from the point of view of patience, good behavior.

People respected more.

Before, tranquility was a beauty and danger was not just around the corner.

One could arrive at dawn, and not now, there is a lot of danger.

But modernism is modernism.

The world of Manuel Patrocinio Algarín Palma, at 104 years old, passes between reflections, prayers, love for life and recitals in his home, as if he were in front of an audience that acclaims him.

His world, after all, is words.

"Are you afraid of death?"

-Why?

If I know that sooner or later it has to arrive.

Do not be afraid of it;

in the other life you live better.

Subscribe here

to the EL PAÍS newsletter on Colombia and receive all the key information on the country's current affairs.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/TGZ4TIGSGJFWBISZ2FULJ7BYDQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/4GRYF43Y55DXTPH55MNNOJUJAY.jfif)