They were all in an archived box.

The senders had sent them from Havana, New York, Tel Aviv or the Chiapas jungle and the recipient was Gabriel García Márquez.

Fidel Castro, in ink, told him that an Italian journalist had interviewed him for 15 hours for television;

Robert Redford asked that the visit to Sundance be "the first of many";

Pablo Neruda confirmed an appointment for him: on July 12 with “Mario, Cortázar and the Donoso” at the Green Horse Tavern in Paris.

There were more than a hundred letters sent to the Colombian writer between 1972 and 2013, but his family, says Emilia García Elizondo, the writer's granddaughter, had never seen them.

The box was in a cabinet with more boxes.

It was white, plastic, and had an inscription on the front that said "grandchildren."

There were supposed to be photos there, but when García Elizondo and his father, Gonzalo García Barcha, opened it, they found 150 letters preserved inside plastic envelopes.

This is how Mercedes Barcha, wife of the intellectual, who died in 2020, had kept them. The family still does not understand what the letters were doing there, since the entire legacy of García Márquez is preserved at the University of Texas in Austin.

The finding was just over a month ago and the descendants of the writer rushed to select the most "interesting".

"We chose those in which the friendship between Gabo and the other person could be read," says the author's granddaughter.

The exhibition 'The writer does have someone who writes to him'. Rodrigo Oropeza

“You're at an age where you probably don't want to be reminded of your age, but if you play your cards right, you can live forever.

So happy birthday”, recommends Robert Redford in a letter signed in 1988, when García Márquez had just turned 61.

The actor wrote that message after the novelist and his wife visited him at the Sundance film festival in Utah, United States.

García Márquez was already, in any case, on his way to that immortality that Redford was telling him about: he had won the Nobel Prize for Literature;

he had published

One Hundred Years of Solitude

, which would become the second most read novel in Spanish after

Don Quixote

, and had written what he considered his best work,

The colonel has no one to write to him

.

A nod to that 1961 book is the title of the sample that brings together thirty of the letters found by the family.

The writer does have someone who writes to him

was inaugurated this Thursday in the house where the author lived in Mexico City until he died in 2014. Simultaneously, another exhibition on the legacy of García Márquez arrives at the Museum of Modern Art starting this Saturday .

The two coincide this year, when four decades have passed since the writer received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982. In the house where García Márquez collected more than 5,000 books, the family set up a space as an exhibition hall and from the Last October they organize events there such as this sample of unknown letters, which is accessed with a ticket of 200 pesos (ten dollars) and prior appointment.

Robert Redford wasn't the only one who wanted to congratulate the writer on March 6.

Bill and Hillary Clinton wish you a "truly memorable" day.

Former Mexican presidents —from Ernesto Zedillo to Enrique Peña Nieto— greet him in a few lines.

Carlos Fuentes celebrates a friendship “of half a century”.

King Juan Carlos sends him a telegram: “Yesterday I tried to call you on the phone (...) Congratulations.

A hug".

Congratulations also arrived for Mercedes, who had her birthday in November.

“These are the mornings that Uncle Joaquín sings to him,” Sabina wrote in 2004, after the publication of

Memoria de mis putas tristes

, the novel in García Márquez narrates the relationship between an old man and a minor: “All whores and sad except Mercedes, / All so smart, so silly with drool, / all vinegar, makeup and salt if you can, / all culiparla except Gaba ”.

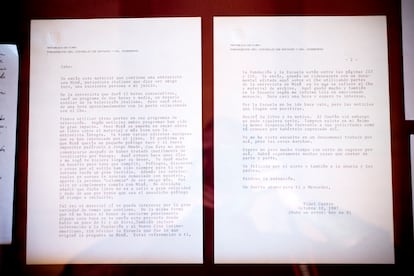

Detail of a letter written by Fidel Castro. Rodrigo Oropeza

There are also letters signed by Fidel Castro that begin with "Dear Gabo."

In one of 1987, the Cuban revolutionary, already at the head of the island's government, narrates his meeting with the Italian journalist Gianni Miná.

"He says he's your friend," Castro writes.

"Miná wanted a little prologue (...) He was here a few days ago and he begged me to send you his wish," he continues.

The letter is written in pointed calligraphy on unfolded white paper.

“I hesitated a lot to do it but I had to comply.

Prologues, speeches and the like have always been a great annoyance for you with good reason.

In addition, the intellectuals in Europe associate you too much with us”, writes Castro, “for this reason, I simply comply with Miná”.

The political commitment of García Márquez, close to the governments and guerrillas of the Latin American left, is also seen in the letters sent to him by Subcomandante Marcos, leader of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, from "the mountains of the Mexican southeast" in July 1994. , six months after the uprising in Chiapas.

The first, apparently, had been lost.

Then Marcos sends him a second one, four pages long.

“Here, like someone who turns to the south that hurts us, we are going to meet to conspire against the shadows that drown us.

Please do us the favor of accompanying us with the light bulb that is in your lyrics”, he invites him and closes: “Okay, teacher.

Even if he doesn't come, we wait for him... Always”.

Fragment of a letter written by Subcomandante Marcos.Rodrigo Oropeza

In 1999, after García Márquez was diagnosed with lymphatic cancer, the letters began to arrive in which they wish him to be better.

“If you need me for anything, call me”, says Woody Allen, “the worst thing about being sick as an adult is that you are not allowed to miss class”.

Honduran writer Tito Monterroso tells him that after the news he did not know what to do: "I have debated between respecting your privacy or breaking it."

The following Saturday they were going to see each other, according to the narrator in his letter, but even so he anticipates "a big hug" from the "old friend of always".

A message from Woody Allen to García Márquez.

Rodrigo Oropeza

The photographer Richard Avedon also begs him that year to allow him to photograph him: “I know you are not feeling well, but it would take me a minimum of time, and I would give the maximum of myself”.

As he explains in the letter, the photograph he had taken of him years ago "under the rain without light" had been a "failure" that haunted him.

“Would you let me try it again?

Could I go to Mexico City to portray you properly? ”, He asks.

García Máquez accepted the proposal and Avedon was able to portray him again in 2004, but he died weeks later and the family did not know anything about those negatives.

Another photo made by Avedon, however, hangs today in the room where the letters are displayed, a glass space, where there is only one other image: the writer, his wife and his two children, one on top of the other, all laughing. .

There are more letters: from Shimon Peres, former prime minister of Israel, who thanks him for such a “warm and refreshing” breakfast and sends him three books;

of Pasqual Maragall, mayor of Barcelona in 1982, who invited him to be part of the Council of Honor of the Arts Festival during the Olympic Games to be held in the city;

of former Secretary General of the United Nations Kofi Annan, who in 2004 thanks him for sharing such “frank and interesting thoughts on the situation in Colombia”.

But García Márquez rarely responded to those messages in writing, García Elizondo says.

"He wasn't one to write letters, he was always talking on the phone," recalls her granddaughter.

Detail of the exhibition, at the House of Literature Gabriel García Márquez.Rodrigo Oropeza

A legacy of more than 27,000 files

As a young man, however, when talking on the phone was still too expensive, García Márquez could not afford anything other than answering in writing.

In those letters, tells the historian Álvaro Santana-Acuña, the young Colombian journalist trying to become a writer is read.

“In one letter, he says that he is trying to be a professional writer but he can't because he has to support his family and he doesn't get good contracts,” explains Santana-Acuña.

“When he is writing

One Hundred Years of Solitude

”, continues the academician, “he expresses that he has doubts about whether the novel is good”.

Only later, when his financial situation improves, do the letters he writes start to be few and short.

The correspondence of his youth is protected by the Harry Ranson Center, the institution of the University of Texas at Austin that preserves the entire Nobel legacy, which also includes originals of published and unpublished works, research material, photographs, scripts, notebooks notes and now recently found cards too.

Although more than 27,000 documents are digitized, others, such as the original of his latest novel,

See You in August

, cannot be viewed online.

In 2020, the center organized the exhibition

The Creation of a Global Writer

to show the material to the public.

After being postponed due to the covid-19 pandemic, the exhibition has moved to Latin America for the first time and from this Saturday it can be toured at the Museum of Modern Art in Mexico City.

The exhibition brings together more than 300 objects.

Santana-Acuña, curator of the exhibition, points out that "the great surprise" during the selection of the material was discovering "the enormous amount of work that the creation of a single page required."

“He was a very perfectionist person,” says Santana-Acuña, who highlights how the author corrected his texts even after they were published: “After the first edition of

El amor en los tiempo del cólera

, for example, he revised the entire text and made changes who slipped quietly into the next edition."

Room of the exhibition 'The writer does have someone who writes to him'.

Rodrigo Oropeza

The visitor will be able to see, for example, the original

One Hundred Years of Solitude

and listen to the author reading the beginning of the novel on a recording.

You will also see one of the electric typewriters where García Márquez wrote before buying his first computer.

"He sometimes complained and said that having started using the computer, his style had worsened," says Santana-Acuña.

There are also statements praising Shakira and congratulations to Rigoberta Menchú for having won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1992. And also very personal objects of the author, such as his birth chart.

The literary agent Carmen Balcells had it made after it was discovered, in 1997, that the intellectual had been born a year earlier than believed.

“She was worried that different things were going to happen to her,” says Santana-Acuña.

"The birth chart shown in the exhibition says no," says the curator,

Detail of a letter written by Pablo Neruda.Rodrigo Oropeza

subscribe here

to the

newsletter

of EL PAÍS México and receive all the informative keys of the current affairs of this country