Dear Ellen Ferrante,

thanks for all your work.

I'm a huge fan, and I've read all of his books, and reading them has allowed me to take new risks with my work.

So thank you for that too.

In this amazing new book you go deep into the things that matter to both readers and writers.

I am very glad to be able to talk with you about these issues.

Questions for Elena Ferrante

1. Writing about artistic mystery is as mysterious as art itself, but you offer an amazing description of what has motivated you and how you have evolved as a writer.

What a riveting read, right up to the exaltation at the end with Dante and Beatrice.

What is the difference between writing a book like this and writing one of her works of fiction?

Are you more aware of her willingness to "stay on the sidelines" with such a book?

And yet, it seems to me that this book also reaches a high degree of exaltation.

2. In her first essay/lecture she describes herself twice as shy, but her work is extremely daring.

I guess this is because the self you describe as shy or worthless disappears into many other selves as you write.

Could it be the 20 people referred to by Virginia Woolf?

I'm right?

She also speaks to this directly when she says that the “excited me” had not written a story, “but another rigorously disciplined me” had.

Can she explain a bit more about these different selves?

I think, I don't know, that we all have different selves.

People without an artistic bent may not be aware of them.

But in acting class, when he was 16, the teacher talked about the different selves that we all have, and for me it was the first time he was mentioned.

And he was (quietly, privately) very liberating.

3. I'm glad you made reference to Virginia Woolf's “bran cake”, how she reaches in and “rummages through the bran cake” while writing a novel.

For many years, I had the feeling, while she was writing, of reaching into a big box and trying to feel the shapes, but I couldn't see them, I could only feel them as she tried to arrange them.

Has there ever been an image of such a thing for you, or do you get by with Virginia Woolf's bran cake?

4. You write: "For me, true writing is that: not an elegant and studied gesture, but a convulsive act."

I am very interested in the two types of writing that you describe in that first lecture.

The writing that stays within the margins, and the writing that becomes, as you say, “almost an act of convulsion”.

Can you tell us more about

when

this transformation happens in the writing itself?

I have other questions for you, but I understood that I should send you some to start with.

If these do not seem appropriate to you, do not bother to answer them, just tell me that they do not work for you, if they do not work.

Thank you very much!

(I've never done anything like this before and feel a bit uneasy.)

Dear Elizabeth,

I appreciate your kind words regarding

In the Margins

.

I really liked your novels

Amy and Isabelle

and

The Burgess Brothers

and of course the wonderful

Olive Kitteridge

.

I must tell you that I value your opinion on

In the Margins

, especially since you have written

My Name is Lucy Barton

, or rather, for the fleeting but memorable relationship between Lucy and the writer Sarah Payne.

I like it when the narrated theme contains within it the story of the effort to write and the problems that writing poses.

Every time that in the vast current literary production, especially the feminine one, I find a novel with this specificity, I underline the paragraphs that interest me and then I place the book on a separate shelf in my library with the intention of returning to it.

My copy of

My Name is Lucy Barton

is there and I'm glad I can now use it for this exchange.

What interested me in Lucy's story?

A double movement: on the one hand, she does not appreciate those who, as creators of verse or prose or art in general, consider themselves superior to the rest of human beings;

On the other hand, she attributes an enormous task to whoever makes poetry with writing or with any other expressive means.

It is a double movement that I have also recognized in myself.

I do not like artists who imagine themselves as shamans and I would prefer that we abandon forever the sacredness of the alphabet, that we carry out the secularization of literature, that in public and in private we stop feeling ourselves little less than below the gods and directly inspired by them.

It was for this purpose - I say this in response to your questions - that I have isolated my

self

who writes, so insecure and precarious, of my other more solid

selves

, occupied in public and private roles.

I've done it to make writing feel like a function no different from many others, sometimes enjoyable, sometimes exhausting, sometimes frustrating.

That's why I really appreciated your Sarah Payne, the writer, when she says to Lucy: I'm just a writer.

If I had to develop Sarah's phrase in my own way, I would say: I am just one of my

selves

, the self that writes.

An unstable self that sometimes is, often sinks, frequently splits into twenty other people, those twenty of whom Woolf speaks ironically: one stops my hand, one wants me diligent and meticulous, one digs to get the light unmentionable things, one suddenly bursts in —there is no precise moment, it may never happen— and pushes me to name those things without respect for anything or anyone.

It is true that, even so, this self can seem a manifestation of exceptionality, albeit a tormented one.

In fact, when I was a child it happened to me like you, I felt different.

I was almost mute or expressed myself in shy monosyllables.

But then my time would come and I had the feeling of sinking a bucket into my head to get words out.

The words carried with them the story.

The further the story progressed, the more the bucket rose and fell at a frantic pace, giving me both pleasure and discomfort, and the more fascinated the other children became.

But was it really different?

No. Think of ordinary conversation when we move forward with disjointed phrases or mincing words, or use an ironic tone that keeps a melodramatic word at bay.

Then, suddenly, unexpectedly, something breaks the margins and the discourse overflows, liberating,

moved, passionate, fierce, until we are ashamed, repent and say: I don't know what he has given me.

Well, the fact that something - a

I

crouched in our brain— grabs us and pulls us away from another prudent or calculating

self

to drag us along imposing its rhythm on us is an experience for all of us.

It is familiar to us, whether or not we are writers.

When that happens in writing, of course, it's different, but all the more reason why we need those sudden breaks in the margins.

When we have great ambitions, the undisciplined irruptions of truths are what motivate our writing.

Your Lucy Barton sets herself a lofty goal, she says: we write to make people feel less alone.

Your Sarah Payne is not far behind when she says: we write to narrate the human condition.

Both, Lucy and Sarah, stand out: you have to write with truth, without protecting anything or anyone;

or also: it is necessary to get rid of all prejudice;

to understand the other you have to go to the bottom.

It is then that the second movement to which I referred before begins, after setting aside the pretense of superiority and the divinization of themselves,

Is it too much for us, ordinary people, who no longer have the old and titanic solidity?

Does the arrogance of the writer's role, thrown out the door, necessarily come back in through the window?

In addition to the self that makes verses or prose or art in general, should we also resize our ambitions and writing become, has it already become, transcribing hackneyed evidence?

Some time ago someone I love told me: "Today, you writers, no matter how humble you behave, deep down you can't accept the idea of not being omniscient, of not being prophets of some god, you still think that your stories enclose in their lines a world that not even the greatest team of specialists in all subjects is capable of deciphering.

Resign yourself, if you do well and someone reads you, you will become part of an otherwise quite irrelevant sector of the immense entertainment industry.

I didn't know what to answer then, today I know but in a confused way.

I would like to know your opinion, if you feel like it.

You have written very powerful books and perhaps you have the clearest ideas.

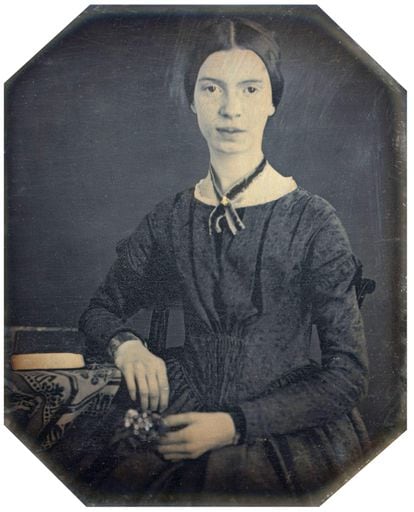

Writer Emily Dickinson.Alamy Stock Photo

Hello again Ellen,

What immediately came to mind when I read your question was Emily Dickinson's poem “I am Nobody!

And who are you?"

I copy it in full here:

I'm nobody!

And who are you?

Are you also Nobody?

Then, we are already two!

Don't tell!

They would trumpet it... you know!

How depressing to be someone!

How vulgar, like a frog.

Say the name of one, throughout the month of June...

To a pond that admires you!

“Say the name of one...” (How I admire her for keeping her name to herself.) But this poem is so fresh, so innocent in a way.

And those first verses I think have always been with me since I first heard them when I was very young, because that's how I feel: happily, that's how I feel.

I'm nobody!

I think very few people understand this about me;

I have been accused (I think) of false modesty, and yet it is neither false nor modest.

It's just that, when I write, the me that people see, the person that people think I am, disappears and I become the text itself.

And when I emerge, my sense of that original self is Nobody again.

It's hard for people to understand.

The way I understand it is that such a thing comes from my very Puritan New England origins, where we were taught that one would

never

he had to draw attention to himself.

(Even today, when someone asks my mom if she's proud of me, she says, "No, why should I be proud of her?" And I certainly understand her answer.)

And yet, I think it's more than just the cultural heritage I've been raised with.

I really almost feel like I don't have a self, even though I know I do.

(I remember when I was a teenager my mother asked me one day with great irritation: “Why can't you be yourself?” And what I didn't say, but thought about it, was: but I am many me).

And yet, here I say that I am nobody.

Because I am.

But I am aware that this is not entirely true.

But it's not fake either.

And therein lies the crux of the matter.

The loved one told him that writers feel omniscient;

what interests me is the phrase “he still thinks that his stories can encompass a world that not even a team of specialists is capable of explaining”.

Frankly, I'd like to think that's true.

That the writers do exactly that, "encompass a world that not even a team of specialists is capable of explaining."

If not, why do I do it?

(I speak for myself.) If it can be explained another way, so be it.

But I want to believe that what I write cannot be explained in any other way than through the story I am telling.

This implies that I am very ambitious, that I am working from that Lucy/Sarah starting point of thinking that I can do it.

And that is true.

Although I never know if I can do it, and many times I fail.

But the me that is Ulis and the ambitious person (me) that tries to write down something that a team of experts is not able to explain... Well, both things are true, being Nobody and being ambitious at the same time;

there we have it.

But when I asked earlier whether our ambitions should be curtailed and whether writing will become—it has already become—a transcription of hackneyed facts, I say very categorically that it will not.

We must not lower our ambitions, and writing—for God's sake, I hope my writing—never becomes a transcription of hackneyed facts.

This is what I believe: it is the pressure between the lines of the text, and the pressure that goes up from below the text, and the pressure that goes out above the text, that gives meaning to the writing;

it is the unwritten that is right next to the written that makes something go beyond the explanation of the team of experts.

And this is what happens when you get out of the margins (if I have understood you correctly) and this is the mysterious thing, what we are looking for.

You say that your loved one told you: "Resign yourself: if you want, and if people read you, you will become part of a sector—quite irrelevant, among other things—of the huge entertainment industry."

I resign myself to it.

But it's not something I reflect on.

He says, before asking my opinion, that at the moment the loved one said that to him for the first time, he did not know how to respond, but today he does, albeit in a confused way.

What, in her confusion, has she come to believe about it?

I would like to ask you one more question: in the third essay/lecture of this book you say: "We make fictions not to make the false seem true, but to tell the most unspeakable truth with absolute fidelity through fiction."

I totally agree with this.

But now I want to ask you about the

voice

.

I found it interesting to learn that he had spent time writing in the third person.

What did you find so liberating about writing in the first person that it allowed you to “tell the most unspeakable truth with absolute fidelity”?

To me, Lucy was his voice.

And in his work, the protagonists are his voice.

His ability to turn Lila into Lenu is a brilliant way to use the first person.

Can you talk a bit more about this choice of first person, as opposed to writing in the third person?

Thank you very much for this conversation.

My dear Elizabeth:

I am pleased with the passion you have put into answering me, I have read you with profit and pleasure.

To expose my point of view —not far from yours, I think— I begin with the question you ask me at the end.

Why have I left the story in the third person?

I answer you in a synthetic way so as not to bore you.

At one point I got the impression that the third person—especially if used very skillfully—is a mess.

In reality, there is no account of the other that is not filtered by a self.

And a third person who does not explicitly have his narrator on stage, from attempt to attempt, it seemed to me, as I explain

In the margins

less and less convincing.

As much as love for others and language as an act of love continuously, insistently, desperately try to overcome the margins of the suffocating first person singular, we remain organically closed bodies in our isolation.

That is why, after taking note of it, I became convinced that for me it is possible to narrate the other only through a self that collides with him and crashes in the collision.

And I have not come out again, at least until now, from this battered first person.

Narrating for me is refusing to go further after having collided, at least with the look, —I quote Baudelaire— with someone who passes, with someone who passes by.

I return to your precious answer — which I will have my friend read — and especially to the quote from Dickinson's poem, which I like very much.

I understand the sense in which you use those verses.

We who write, you say, are just ordinary people with our limited experience as individuals, with our historical and cultural roots.

And when we get to work we get so lost in the alphabet that we coincide with the thread of our own writing.

But —as you yourself point out— the thread of that writing is and will continue to be full of great ambitions, even if we don't feel possessed by a demon, even if we aren't oracles, even if we don't consider ourselves Someone, even if often we don't even feel like reaching to be someone

me

biographically defined.

Nobody—Dickinson's Nobody, wholly different from Odysseus' cunning Nobody—is (now my opinion) perhaps the true name of every woman who writes, since she writes from within an essentially masculine tradition.

We try to use the specificity of writing as best as possible (you have effectively defined it).

We draw on the resources stored in the multi-millennial repository of literature.

We put the cube in our very normal brain and we get words and memory.

But these belong to us little or nothing.

So, if we're honest, it didn't take long for us to painfully overwhelm ourselves with the permanent pushes of the other and, surpassing the margins, with excessive ambition we look for our names today.

We are not interested in having a name, making ourselves a name;

The friend I told you about says: go ahead, at most you will contribute to the entertainment industry.

I have nothing against entertainment as long as it allows me to remain Nobody and just writing.

I adore Dickinson's frogs, they are the other, the others, the others, and I am passionate about his vicissitudes.

Our writing wants —and when it is worthwhile it must— to disconcert and disconcert them.

What's wrong if we finally strive to reinvent the choirs of June with our scores and our voices?

We, women, are Nobody, but our writing is very ambitious, as much or more than Dante's, who was extremely ambitious and that is why he wanted to sink into each thing, each person, to dig deep: that is why he

invented verbs like

enellarse

,

enelarse

,

entiarse

,

enmiarse

(with the sense of entering her, entering him, entering you, entering me).

Like you, my dear Elizabeth, I am for true modesty and true generous ambition.

I would like all women who want to write to have a common practice of disruptive writing, which tries to transmit a tremor first to ourselves and then to all forms;

a writing that has that tremor, the disorder it causes, the compositions it decomposes, the effort to redesign the margins of History and of all histories.

Thank you, a hug and I hope there will be more opportunities to talk.

Elena

Translation from English (Elizabeth Strout letters) by Newsclips.

Translation from Italian (letters by Elena Ferrante) by Celia Filipetto.

This article originally appeared in The Guardian newspaper on March 5, 2022.

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.