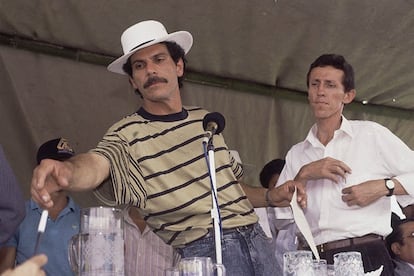

Gustavo Petro during Antonio Navarro Wolff's Senate campaign. GUSTAVO PETRO PRESS

The night that Gustavo Petro won the presidency, one of the leftist sympathizers who wept when the victory was announced was Germán Navas Talero, a representative for Bogotá since 1998 in Congress.

“Since I was 14 years old I have been a member of the left, now I am 81 years old, and since I was 14 I have been waiting for this change, I thought it would never come,” says the congressman, who recently retired from politics.

When Petro's victory was a fact, a recording recorded Navas removing his glasses to wipe his tears with a handkerchief, and a teammate yelling "Thank you Navas!"

and “He did not leave this world without the left winning!”

The congressman tells El PAÍS that he cried that night "partly because of rhinitis, and partly because of emotion: it was the dream of my youth, and now it is the dream of my old age."

He wasn't the only one who spoke of dreams that night.

In his victory speech, Petro himself said that he thought that such a day would never come: "I thank you for this historic day, I dreamed of it from time to time, I wondered if it was going to be possible."

And it is that perhaps the closest thing that Colombia has been to the left before Petro was during the government of former president Alfonso López Pumarejo, of the liberal party, who in the thirties carried out a number of social reforms that he called “The revolution in March".

Since then, there have been some progressive governments, but never in history has a presidential candidate from a left-wing party won.

For decades, being on the left in Colombia was a stigmatized term, almost synonymous with being a guerrilla, or a Chavista, or hopefully, being a tremendous delusional.

When the entire region turned to the left in the first decade of the 21st century—Hugo Chávez, Evo Morales, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, Michelle Bachelet, Lula da Silva—Colombia turned further to the right, electing former president Álvaro Uribe.

But although the left always had a very limited space of oxygen in Colombian democracy, it managed to slowly weave a path to power.

Petro won, in part, by collecting those efforts from the past, of which Navas Talero was a part, and many more.

There were four key moments in recent history before Gustavo Petro was elected: the creation of the 1991 Constitution, the formation of new political leadership, the 2016 peace process, and the social upheaval of the last three years.

León Valencia is a political analyst and also a militant of the left, who in the 1990s laid down his arms after being with the ELN guerrillas.

"I was a central commander and I must admit that those who always had the greatest lucidity at that time to act in a democracy were those of the M-19", says Valencia.

The M-19 was one of several guerrillas that were active in Colombia during the 1980s, and of which Petro was a part.

"And history rewarded them, gave them a new president," adds Valencia.

Carlos Pizarro and Antonio Navarro Wolff, leaders of the M-19, signed a peace agreement in 1990. Pizarro was assassinated the same year.

Navarro was later co-president of the National Constituent Assembly that drafted the 1991 political charter. COURTESY

The road to democracy for the left was almost impossible.

Its militants could not participate as a party during the National Front - the period from 1957 to the end of the 1970s in which only the Liberal and Conservative parties took turns in power.

Sympathizers in those decades joined an armed group or militated as citizens outside the parties, although in the eighties they were severely persecuted by the state.

The Patriotic Union, for example, a party that had been born in a peace process with the FARC, was eliminated by state forces and paramilitaries: at least 8,300 citizens were victims, 5,733 disappeared, according to the Special Justice Court for the Peace.

Being a candidate for the left seemed to be a death sentence.

Before the 1990 elections, four presidential candidates were assassinated: Bernardo Jaramillo and Jaime Pardo Leal of the Patriotic Union, Carlos Pizarro, of the demobilized M-19, and Luis Carlos Galán of the New Liberalism.

As the historian Pablo Stefanoni wrote, that Petro has reached the presidency of Colombia alive as a leftist candidate, despite being seriously threatened, is not a detail.

“Arriving alive and winning is already going down in history,” he writes.

The M-19, however, managed to negotiate a peace agreement at the end of the 1980s and generate new leadership.

Despite the attacks, the extinct guerrilla managed to become a leftist political party that was the third force in the process of writing a new constitution: that of 1991, which defends a Social State of Law.

A more progressive constitution that included the right to decent housing, health, or life.

“The 1991 Constitution was a victory for progressive sectors,” says Iván Cepeda, a senator and leftist militant close to Gustavo Petro.

“It coincided that in history there was a victory of the so-called socialist camp, which implied the emergence of a different, renewed left, and another type of leadership centered on the spirit of the constitution.

I am going to name, for example, the figure of Carlos Gaviria”.

Carlos Gaviria was a central figure for the left, first as a progressive magistrate in the new Constitutional Court, and later as the first presidential candidate to manage to compete against the traditional parties from a leftist party, the Polo Democrático Alternativo.

In the 2006 elections he was the second most voted candidate, after Álvaro Uribe, and above the Liberal Party.

"Gaviria was a figure that did not come from the Soviet model," says Senator Iván Cepeda.

“His discourse on political change was linked to democratic achievements, such as for example that the social state of law exists in a society, that rights were a reality, that the social approach of the foundation of the state be defended.

That implied not monopolizing property, for example, and that is why it is so absurd that the left was accused these years of wanting to expropriate the people —as Petro was accused in this campaign—, because for a long time the left Colombian has a reformist view of society.

Petro was co-founder of the Polo Democrático, a party that later managed to reach the mayor's office of Bogotá, the governor of the department of Nariño, and managed to consolidate a small caucus in congress, among other popularly elected positions.

The left of Polo was divided by a case of corruption against two of the leaders - the Moreno brothers - that Gustavo Petro denounced before separating from Polo and going to found the Colombia Humana party.

Years later, he organized the winning movement in these elections, the Historical Pact, where many of his former allies are.

Carlos Gaviria greets Gustavo Petro, during the Alternative Democratic Pole Congress in February 2009, in Bogotá. OMAR VERA

But there was one last element in this long road of the left: the 2016 peace process, with which thousands of soldiers were demobilized in what was the largest guerrilla group in the country, the FARC.

"If the FARC continued in guerrilla life, Petro would never have won," says analyst León Valencia.

"Because the discourse of the right, which fuses the left with the guerrillas, would have been maintained."

Looking at the electoral map, it is clear that the areas that supported the peace agreement in 2016 —those that voted yes to the plebiscite, several of the most affected by the armed conflict— are the same ones that mobilized en masse to vote for Petro: the Pacific and the Colombian Caribbean, the south of the country, and the capital, Bogotá.

In municipalities like Timbiquí, on the country's Pacific coast and where the majority of the population is Afro-Colombian, Petro won with 98% of the vote.

"The black vote votes for peace, the black vote votes for change, the black vote votes for a social justice agenda," explained Ali Bantu Ashanti, director of the Racial Justice lawyers' collective, after the first round. followed up on electoral crimes in these elections.

Electoral support rose sharply in the Pacific as Petro allied himself with Francia Márquez as his vice-presidential running mate, an environmental activist who has been a victim of war and who represents the most excluded sectors of society.

The pragmatism of the candidate in this campaign to make alliances, having supported the social movement for the last three years, and even the inequality generated by the pandemic also played in favor of Petro.

But also this long history of the left that, despite the violence and divisions, has not disappeared.

Navas Talero, the representative from Bogotá, agrees that the current moment is linked to the initial efforts of the Polo, of Carlos Gaviria, of leftist militants who were assassinated.

But, he adds, "I think it also has to do with perseverance, and now we won thanks to Petro's perseverance."

The day after the election, he wrote a message directly to the president-elect.

“Gustavo fulfilled your dream.

The win is well deserved.

I did what I could because you were the realization of my dream on the left, ”he wrote on Twitter.

"The dream came true.

Good luck Gustavo”

Subscribe here

to the EL PAÍS newsletter on Colombia and receive all the key information on the country's current affairs.