Gustavo Petro learned that he was going to be president of Colombia at 4:20 p.m. on Sunday, June 19.

When the third bulletin of the electoral count came out, with 4.47% counted, he was certain of a long-awaited victory.

Alone in his room, while the screams of his circle of trust thundered outside, he felt a kind of inner collapse that he describes as a "deep torpor."

“When everything falls, when the adrenaline leaves you, it is as if a building fell on you.

I threw myself on the bed,” he says.

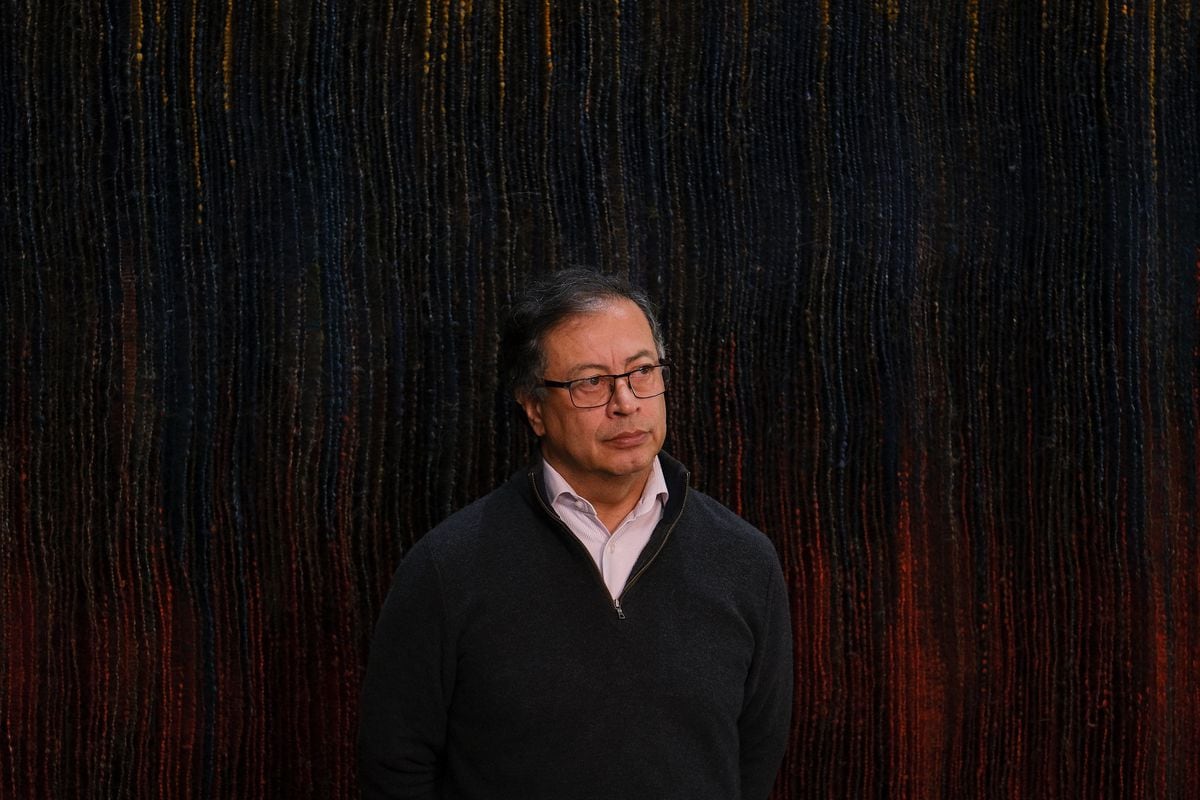

Petro, 62, was sitting on a soft sofa in his house in Chía, in an urbanization 15 kilometers from Bogotá.

Wear light jacket, Mao collar shirt,

jeans

and buckled shoes.

Overcome the torpor, which he confesses lasted two days, he looks relaxed, much more than when he was a candidate.

From time to time he touches the Saint Benedict medal, a gift from the Pope, which he wears on his left wrist, and to most of the questions he answers without too many circumlocutions, something that was almost impossible before.

He transmits an inner calm that only has one vanishing point: when an issue agitates him, he stamps his feet on the ground, emphasizing the end of the sentence.

He does so by talking about poverty, big capital and tax reform, a measure that he promises to carry out as soon as possible and that cost the current president, Iván Duque, a popular uprising.

"Reforms are made in the first year or they are not made," says the person who will be Colombia's first left-wing president on August 7.

During the Interview,

Ask.

Why has it taken Colombia so long to have a leftist president?

Don't you feel that if you fail, the doors will be closed to other candidates in the future?

Response.

If I fail, the darkness will come and destroy everything, and I cannot flee.

Q.

What darkness are you referring to?

A.

We have launched a formidable challenge.

It was unlikely that I would make it to the end of the electoral process alive.

And now, if my Government establishes the conditions of the transition, what follows is a new era.

And if we fail, what comes, by physical law, is the reaction.

And a reaction in which Uribe is not the protagonist.

Life cycles change.

There are circles organizing around fascism.

We are not going to attack them, for now, none of that, but we are going to take into account that this is happening.

Q.

You were a guerrilla, you belonged to the M-19.

He wanted to come to power through arms.

He has come to power by the contest of votes...

R.

I have reached the Government...

P.

To the presidency.

Were you wrong when you were young?

A.

No. That is like asking if Bolívar was wrong to take up arms against Spain and found a republic.

It's the story.

Could it have been otherwise?

You go to know.

Could Bolívar have been Gandhi?

These are all mind games.

Let's say that we took up arms against a tyranny and the product of that is the 1991 Constitution, which we and others made.

And I am the Government of the Constitution of 91. That is the story.

You can always say this could have been like this or that, but the story is not post, it is always before.

Decisions are made and the story moves on.

Q.

You mentioned physical risk.

Are you afraid there may be an attack?

R.

It is always feared.

There are always violent possibilities.

You have to decrease them.

That exist.

Q.

Your project is going to encounter resistance.

For example, in the army, the person in charge of it, General Eduardo Zapateiro, criticized him in the middle of the campaign.

What are you going to do with it?

R.

The domes are coming out.

In every government there are changes.

This dome was very imbued by the political line of the Executive that ends.

But this path is unsustainable and makes the public force itself a victim, which has been led to perpetrate Dantesque acts against human rights.

What we propose will lead the public force to a greater democratic strengthening.

Q.

Do you not fear any adverse gesture on the part of the Generalate?

R.

There are currents of the extreme right that must be eliminated.

Some are proclaiming coups and things like that.

But look, within the army there are no factions friendly to Gustavo Petro, there are factions friendly to the Constitution.

And that is what needs to be developed, an army that obeys the Constitution, regardless of the governments that pass.

Q.

Colombia shows a clear division.

What are you going to do to overcome that fracture?

R.

I have called a great national agreement to try to build a different political climate.

I will chat with Álvaro Uribe and with Rodolfo Hernández.

It is time to make reforms, not to leave things as they are.

We must avoid sectarian confrontation and open a civilized dialogue.

And you also have to seek peace.

The political climate can encourage or dampen violence.

One of my purposes is to achieve as much peace as possible in Colombia.

P.

How will your treatment with the opposition be?

R.

We are not going to build a government that persecutes the opposition.

We have been victims of that.

The intelligence system is not going to target the opposition, but rather corruption.

If they feel confident in our government and that there will be no persecution and that they will be respected in the political, personal and family spheres, I think we can build.

They will also be able to make an opposition as they have the right to do it: controlling our Government.

Colombian President-elect Gustavo Petro at his home in Chía, on the outskirts of Bogotá, on June 27, 2022. Camilo Rozo

P.

What is going to be your first measure when you are president?

R.

I am worried about hunger, which already reaches levels of 20% to 25% of the population.

And poverty is around 40% despite the economic recovery and the decline of the virus.

In addition, it can be felt that a global economic depression is approaching.

The winds are not in your favor.

That is where I see that the first urgent measures must be taken.

Q.

In your victory speech you defended democratic capitalism.

He did it to remove the stigma of radical leftist?

R.

Capitalism does not tend to be democratic.

For it to be, the effort of the State is needed.

The economic base in Colombia is fundamentally made up of millions of small businesses, with very little associative capacity.

It is a very simple market economy.

It is not capitalism that is there, it is a pre-modern form of economic activity.

They must be given a credit capacity that boosts agricultural and industrial production.

That can be called populism, but it is what I call democratic capitalism.

Until now, governments have privileged open-pit mining and traditional monopolies that have given rise to great fortunes, but that do not account for even 5% of jobs in Colombia.

Q.

You have always been very critical of big capital, of the establishment.

He has said that the owners of the big conglomerates are against him, that they use the media to attack him.

What is he going to do against big capital?

R.

To pay taxes, basically.

But the big capital that affects the environment, such as the fossil economy or the extraction of hydrocarbons, has no future with us.

You will have it if you associate with the peasantry and pay taxes.

Q.

In that sense, one of your great promises is agrarian reform.

How do you intend to achieve it?

Will you meet resistance?

R.

Yes, obviously.

Land tenure in Colombia is feudal.

It is a derivation of the Spanish colony that has never been overcome because every time it was attempted there was violence.

The country never managed to carry out an agrarian reform.

Today, we try again and, I will confess, I would like to do it hand in hand with the United States.

Unlike in the past, the agrarian reform is linked to the possibility of a substantial decrease in cocaine exports.

The United States has concentrated its effort in a very ineffective way on glyphosate and extraditions.

The result has been a total failure.

P.

Have you mentioned it to President Biden in the call you had?

A.

(Laughs) No, no, no.

In fact, we had communication difficulties with the embassy in the campaign.

P.

The United States ambassador in Colombia never called you, right?

R.

Once we won the elections it was very fluid, paradoxically.

Two days later I received the call from Biden, which is very symptomatic.

It means that they are interested in establishing a constructive dialogue with us.

P.

You have spoken of agrarian reform and reduction of poverty;

they are big projects that possibly require decades or generations.

But isn't four years a very short time to achieve it?

R.

My Government has to generate beginnings, because they are long-term issues.

I call it the Government of transitions.

An era begins and we hope it will continue.

That will depend on Colombian society, on their votes, on whether they want to go back again or move forward.

In that we are going to resemble Chile, in its effort to build democracy.

Spain is also an example: it came from a fascist era to a democratic one.

And it has been an ongoing process.

It is society that takes steps forward and, in the end, the democratic idea becomes irreversible.

The same thing is going to happen here.

P.

You have appointed the conservative Álvaro Durán Leyva as chancellor.

What message do you want to send?

R.

Leyva is quite conservative, but he made the 1991 Constitution and has been a peacemaker for many years, both with the FARC and the ELN.

And peace in Colombia needs world help, because today it has to do with the climate crisis and drug trafficking.

40 years ago it was a much more political issue, linked to the cold war, but now the complexity is higher and we need the world to show solidarity.

P.

And what role do you want to give to the Catholic Church in this construction of peace?

R.

As a mediator.

And I proposed it to the Pope, I told it (not publicly) to the Nunciature and the president of the Episcopal Conference.

That was there.

Now I have to get back to it.

The Catholic Church is today the only entity that knows the specificity of the conflict in each region and can help a lot in pacification.

Q.

Are you thinking of the president of the Truth Commission, the Jesuit Francisco de Roux?

R.

It will be the person determined by the Church.

Q.

That is, the mediator they name will accept.

R.

_

Yes, the one they put.

Obviously, the Government has a job to do to achieve the peaceful dismantling of drug trafficking.

We hear many rumors that a debate has begun in the armed organizations about what to do.

Petro, 62, learned that he was going to be president of Colombia at 4:20 p.m. on Sunday, June 19. Camilo Rozo

P.

And do you have parliamentary capacity to approve a legal reform to facilitate negotiation in judicial terms?

A.

Right now, yes.

Q.

Are you worried that time will pass?

R.

Yes. The reforms are made the first year or they are not made.

P.

The tax too?

R.

The tax has to be this year.

Q.

And aren't you afraid of a social explosion like what happened to Iván Duque?

R.

No, because this reform will not fall on the pockets of the people, but on the privileged layers.

P.

And do you plan to call big capital, businessmen and bankers to open a dialogue with them?

R.

That is what the great national agreement is about.

We are going to reform the tax law and we have invited you to discuss the issue.

The Colombian tax system is relatively progressive up to the upper middle class, which pays more taxes than the middle class, which pays more taxes than the popular class.

But above the upper middle class lies injustice.

A banker pays proportionally less taxes than the secretary in his office.

And that cannot be so.

It is about progressivity until the end.

This would reduce the fiscal deficit, improve macroeconomic conditions and allow financing progress in the rights of the Colombian population.

That is what I consider the social pact.

It goes through the will of big capital to pay its taxes.

Q.

What do you think of Gilinski's takeover bid for Grupo Empresarial Antioqueño?

R.

It is the logic of big capital.

But they are doing it under Colombian standards.

And in the face of this type of dispute, the institutional framework must maintain total neutrality.

Q.

Even if it has capital from Saudi Arabia?

A.

Big capital has no country.

Q.

You have proposed resuming diplomatic relations with Venezuela and reopening the border.

Will that be enough?

R.

It is a complex issue that will not be solved overnight by restarting diplomatic relations.

In Venezuela there are millions of Colombians who need to resolve their consular issues, titles, papers..., and here there are two million Venezuelans with their own problems.

We must help those who want to return.

And Venezuelans who want to stay in Colombia must enjoy rights, not simply immigration protection, but the right to health, education, child care, validation of a title... All of this must be set it.

The same happens with the Colombians who were orphaned in Venezuela.

There is such a magnitude of accumulated problems that the effort must be very great for things to return to normal.

P.

There are Venezuelan exiles, activists and journalists persecuted by the Chavista regime, who fear that when relations are restored they could be extradited to Venezuela.

A.

No, not at all.

Q.

Is that not going to happen?

R.

For us, human rights are fundamental.

The first discussion I had with Chávez while he was alive, and perhaps the last one before he died, was precisely about respect for the inter-American human rights system, which for those of us who have been in the opposition in Colombia is extremely valuable.

Many of us owe him—myself included—our lives.

And Chavez decided to take Venezuela out of the system...

Q.

And don't you think that Venezuela would do better with a democratic system with full guarantees and another president?

R.

Venezuela would do better if its people dialogue with each other, in all its plurality, and if they are the ones who make their decisions about the elections and their mechanisms.

What we have is to help.

P.

There are those who speak of a new progressive axis in Latin America, formed by the presidents of Mexico, Argentina, Chile, now Colombia and in the future perhaps Brazil.

Do you feel identified?

R.

I would say that there are two phases.

A first based on fossil fuels, which we could call the Chavez phase.

There was like a golden age of social welfare, but it was unsustainable, because it was based on oil.

All of that collapsed.

Now, it's time to abandon the fossil fuel economy, disassociate ourselves from oil, coal and gas, and build development on the basis of production and knowledge.

Progressivism is not very clear on this in Latin America.

But for me no progressive vision of society can be built on the fossil economy, because the fossil economy is death.

We must consider a new model of development in Latin America, that is our role in the agenda, our legacy.

And that is going to be the topic of discussion in that axis.

Gustavo Petro, in an interview with the newspaper EL PAÍS, at his home in Chía, on the outskirts of Bogotá. Camilo Rozo

Q.

Will you form a parity government?

R.

Yes, that is my commitment.

P.

A year ago you criticized that feminism had become outdated...

R.

You are going to put me in another mess.

P.

Since then you have qualified your positions.

What do you think now as president?

R.

I think that we must empower millions of women in Colombia, the vast majority in the rural world.

With dynamics and aspiration agendas that must be met.

It is not about a woman being able to create a company or start a business, the issue is how millions of women can have power.

P.

Your daughter Sofía said that you were a man in the process of deconstruction.

Is it so?

R.

That term is very French.

To a Colombian, deconstruction sounds like destruction.

But yes, it is a deconstruction.

But it's not just me, there are millions of men in Colombia who are in the process of deconstruction.

P.

What would you like them to say about you when the mandate ends?

R.

We have three objectives: peace, social justice and environmental justice.

If at the end of the mandate I have advanced in all three, great.

It will be the best government in history.