Austrian philosopher Franz Brentano.

The sky is my homeland and, my job, the contemplation of the stars.

Anaxagoras

Creation exists, but it is not finished.

The debate between creationists and evolutionists is a sterile debate, in which both sides hide their real motives.

A pseudo problem, like so many others.

The works of Aristotle have not reached us.

Only his lecture notes, preserved by Arabs and Persians.

There is no

Metaphysics

or

Logic

finished and published by the philosopher, only the materials for his lessons at the Lyceum.

Franz Brentano wrote numerous works on Aristotle and, following the example of the master, did not give them to print.

Those drafts, provisional and incomplete, tentative, were also teaching materials.

He who has just written a book and sends it to the printer believes that he has finished his work, but he is mistaken.

Any work that is worthwhile is a work in progress, unfinished.

Like Aristotle's, which is still commented on, like Brentano's, now almost forgotten, like that of this universe, proud and expanding.

All of them open attempts, unfinished,

with its weaknesses and its strength.

Brentano's family is unique.

His grandfather, a wealthy widower of Jewish descent, leaves Lake Como in Italy and settles in Frankfurt shortly before the outbreak of Romanticism.

There he marries an old friend of Goethe's who has inspired some of

Werther 's characters.

.

Maximiliane von La Roche bears him three children.

The first is the poet Clemens Brentano, a romantic and mystic, who leads a hallucinated and exciting life, which will be told by his sister Elisabeth.

Bettina, as they call her, is also a poet and a fascinating woman.

Extremely cultured and feminine, she corresponds as a child with Goethe (who falls in love with her, dirty old man) and as an adult, with Beethoven (when the great deaf man is devastated by illness and megalomania).

Later, she becomes a libertarian socialist.

The third of her children, Christian, austere, pious, with strong Catholic morals, is the father of the philosopher.

A man concerned with metaphysics, specifically with God's intervention in the world.

An essential theme of phenomenology (which his son helps found), only where Christian says God,

Brentano conceives a hierarchy in the scientific disciplines.

Mathematics is the simplest and primary.

On it rises physics, then chemistry, and finally physiology.

Brentano was born in 1838. He received a religious and poetic education.

In the arms of his uncle Clemens he listens to the great poems of the German language.

His father dies soon (a factor that favors the philosophical life) and, despite the pious atmosphere that surrounds him, or precisely because of it, as an adolescent he suffers a deep spiritual crisis.

The reason: determinism (the completed creation).

He seeks refuge in philosophy, which he studies in Munich, Berlin, and Münster, and then in theology, which he learns from the Dominicans in Graz and later in Wurzburg.

At the age of 26, he is ordained a priest and qualified as a theologian at the university.

He teaches history of philosophy.

He warms up to Aristotle and the medieval commentators on him.

His classes leave a deep impression on the students.

He has an unquestionable attractiveness and looks of a prophet.

On the class platform

is transfigured.

The youth crisis has thrown him into a rigorous orthodoxy.

But so much rigor will get him out of it.

In the background, the eternal rivalry between Dominicans and Jesuits.

The reason: the dogma of the infallibility of the pope.

The German bishops meet and commission Brentano to write a letter opposing the declaration.

But the dogma is confirmed and Brentano retires to meditate at the Monastery of San Bonifacio.

Finally, he breaks with the Church and resigns from the priesthood.

In 1874 he is called to Vienna and appointed ordinary professor of philosophy.

Since he occupies until he falls in love.

He acquires Saxon citizenship and marries as a foreigner in Austria (Austrian law prohibits ex-priests from marrying), so he has to give up his position and remain as a private teacher.

Sober in words and content in habits, he neither smokes nor drinks.

A twist of thought

Brentano marks a turning point in the history of modern thought.

For Ortega, “the most rigorous and scientific philosophy comes from Brentano”.

He is one of those figures who work from underground, unnoticed, and who powerfully influence the course of thought.

His influence is, in many ways, Socratic.

Like Spinoza, he develops his teaching at the risk of intimate, almost secret circles of friendship.

He has "the merit of restoring true philosophy, spoiled by Kant", concentrating on essential questions of metaphysics, ethics and psychology.

This break with Kant and with the positivists opens the way to the phenomenology of the intentional mind.

What Kant calls a priori knowledge, for Brentano are a priori convictions, almost prejudices.

The world has its causes and effects, its reasons,

but among them we must count the beings, with their inclinations and intentions.

The world is not a complex mechanism, it is more like an organism where consciousness turns into the physical, not passively, but intentionally.

This attitude can try to define its object to, knowing it, dominate it;

or, in a more contemplative way, observe it to glimpse its nature.

Be that as it may, the method must adhere to the nature of the object (as Aristotle teaches).

Brentano does not yet consider, as Bohr will do later, the difficulty of considering that nature as something "virgin".

The object is always something already defined by theory or tradition.

How to make the object print its characteristics to the method if, to observe it, we need an instrument and if, to build it,

do we need a theory and a prior idea of its nature?

Saying that the method must fit the object is a compromise, since the object already has to be something to us before parsing it.

In any case, intentionality is the essential factor of the mental, which is why it conditions all conscious experience.

Brentano shares with the positivists his rejection of ideal objects and his commitment to a knowledge limited to experience.

But the experience requires the full participation of the observer, that is, mental inclinations and intentional positioning.

There are reasons and intentions and, if we stick to experience, we cannot separate one from the other.

For a naive positivist or realist, consciousness is just another piece of the cosmos.

For Brentano, the physical and the mental have different natures.

Idealism has left Germany exhausted.

As a young man, like all the restless young people who studied after Hegel, Brentano was interested in positivism, but ended up finding it superficial and bourgeois.

The positivist is not surprised.

He is not interested in knowing, but in anticipating.

He wants to anticipate, control.

He is satisfied with ordering phenomena in space and time, he conceives (with Bacon) knowledge as a way to increase human power.

Brentano conceives a hierarchy in the scientific disciplines.

Mathematics is the simplest and most primary of the sciences.

Physics is built on it, then chemistry and, finally, physiology.

The psychic phenomena behave with respect to the physiological in the same way that these behave with respect to the chemical ones.

Physiology must reach its highest degree of perfection so that psychology can develop.

Psychology is, in turn, the foundation of sociology.

Each reality requires a particular method to know it: it is useless to contemplate the landscape with the microscope.

Bohr will delve into this idea.

Theory not only builds the object, it also builds the instrument with which to observe it.

Seeing is believing.

Without a theory it is not possible to see anything.

A purely physiological reason for something is just as banal as a purely mathematical reason.

Belief is a force of nature.

Every theoretical framework points to a belief.

The idea, of course, comes from scholasticism.

philosophy is

preambula fidei

, an introduction to faith.

An idea that William James and Ortega y Gasset will develop.

In his 1892 habilitation thesis, Brentano maintains that the true method of philosophy is that of the natural sciences.

These do not require that we should proceed uniformly (as in the simple cases of mechanics), but "that it teaches us to change our procedures according to the special nature of the objects."

While mechanics is ahistorical, embryology, geology, or biology are not.

And temporality is essential for the sciences of the spirit (mechanics has neither a past nor a future).

Therein lies the difference between the spiritual and natural sciences.

Some are dedicated to an immobile and eternal principle, while the others comprise history and its (dynamic) force vectors.

Life is a gerund, not a participle (Ortega would say), it is the temporal conjugation of a nature in history,

in evolution.

It is not always possible to isolate phenomena in the laboratory.

Or because of the great distance that separates the cause from the effect.

The disputes between the different scientific disciplines are verbal disputes (and knowledge is reduced to dispute, to logical juggling and mental agility).

Brentano seeks a method that conforms to the nature of things and it is they who have to determine the method of investigation.

If we want to know, we must be the ones who adapt to the objects.

without prejudice or

Brentano seeks a method that conforms to the nature of things and it is they who have to determine the method of investigation.

If we want to know, we must be the ones who adapt to the objects.

without prejudice or

Brentano seeks a method that conforms to the nature of things and it is they who have to determine the method of investigation.

If we want to know, we must be the ones who adapt to the objects.

without prejudice or

a priori

.

Kant calls a priori knowledge what is actually an "a priori conviction."

Brentano detects a certain circularity in the approach: “The same things are, at the same time, problems and solutions”.

The truth is only one.

But the languages are many and each one expresses different aspects of it.

Philosophy is feminine.

She weaves and unweaves, like Penelope, while she waits.

Brentano is serene and, although he vibrates intensely, he does not let himself be intoxicated like Nietzsche.

As a southerner, he does not fit into the metaphysical lukewarmness of positivism, which seems to slip on the surface of things.

He looks for a pre-modern meaning, in medieval Aristotelianism (Avicenna and Aquinas) and in the Stagirite itself.

Among the moderns, his favorite is Leibniz.

Already in 1886, from Vienna, he writes to a friend: "I am, for now, completely metaphysical."

The history of philosophy is more like the history of art than the history of the sciences.

Philosophy, like art, if it is clairvoyant, goes ahead, anticipates new landscapes and new scenarios of reality.

For Brentano, philosophy moves cyclically, going through various phases in each period.

In the first, ascending phase, the interest is purely theoretical.

It is followed by a second phase of decadence, moralistic, where scientific interest weakens and where "logic and physics lead a depressed existence as servants of ethics".

This leads to a third, skepticism.

Science is no longer trustworthy.

That sickening zeal finally leads to the formation of new dogmas and returns philosophy to the first phase.

These cycles can be traced both in the ancient world, as in the medieval and modern.

Aristotle Reader

One cannot be an inveterate Aristotelian, as Brentano is, without being Platonic at times.

Neither is radical Platonism possible, without being at times Aristotelian.

Between both positions lies the game of philosophy.

Induction, which goes from the particular to the general, is Aristotle's way.

The deduction, which goes from the general to the particular, that of Plato.

William James, with his usual humor, reminded us that no one can live even half an hour without being, at the same time, Platonist and Aristotelian.

Induction and deduction are complementary.

The world is not made from the simple to the complex, but neither is it built from above.

Both directions establish cognitive circularity, which is cosmic circularity.

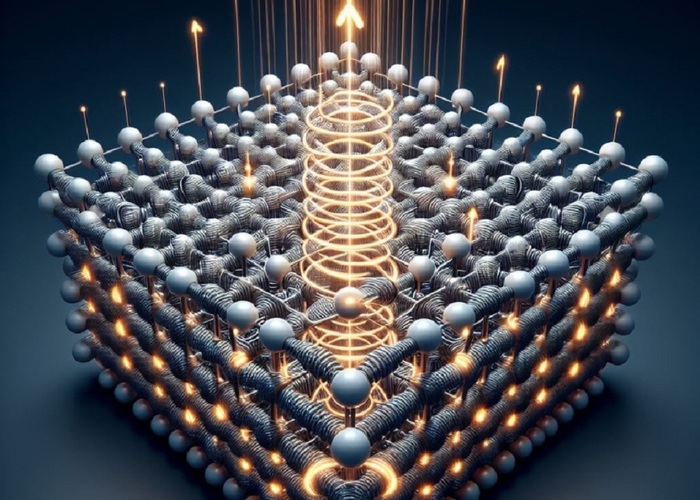

The Universal Entanglement.

There are up to six essays by Brentano on Aristotle's categories.

For the stagirite there are ten kinds of being: substance and nine accidents (quality, quantity, place, time, action, passion, relationship, position and habit).

A scheme that Aristotle leaves unfinished.

A promising theory, but inconclusive.

Neoplatonists also participate.

Plotinus reduces the categories to four (substance, inherent accident, movement, and relationship).

For Brentano, all the confusion on the matter comes from considering categories as logical tools.

The categories are a doctrine of being, ontological.

Turning them into logical categories makes them lose their genuine meaning.

Life is not mathematics, Brentano might have said.

But Kant and the positivists mathematize it, and thereby lose themselves.

The substance is an entity that has a special relationship with the others, it is not subordinate to other things, as the species is to the genus.

Substance is what makes a thing itself and not another.

In a certain sense, it is autarchic and homogeneous, and it is free from extrinsic determinations.

Substance is the great core of philosophy.

No one knows exactly what it is, but it must be postulated if we want to talk about the world, adapt it to language.

The relationship between substance and accident is a relationship of complementarity and intimate involvement.

The substance of the human animal-rational being is enriched with laughter, love and mortality.

It is not a cause and effect relationship, as Descartes believed.

For the French the substance is a cause that always remains in itself and by itself, it is a thing (

res extensive

) that supports accidents, is a thought (

res cogitans

) that supports spiritual accidents.

This entails a disaster, which in modern times is revealed by the association of the concept of substance with that of matter, with mass, with what is hard and impenetrable, with what has position and movement, with primary qualities, turning the world in a meccano complex (and let us remember that, according to the laws of mechanics, time does not pass).

With this, it is possible to transform the universe into something inert and devoid of life (manipulated, exploitable).

It is dislodging life from the very center of philosophy, which is where it should be.

With these approaches, says Brentano, both Descartes and Spinoza move away from Aristotle, and not only that, they also move away from the truth.

Kant ends the disaster.

Rectifying this error is fundamental, although Brentano does not finish creating a modern Aristotelianism.

He insists on his empiricism and accuses Husserl and Meinong of returning to Platonism.

He recognizes the necessity of the existence of an entity that is not contingent, of a necessary entity.

But nothing physical and nothing psychic is necessary per se.

Therefore, said entity must be transcendent to the physical and psychic world.

Furthermore, if creation is a necessity of the necessary Being, either it must always exist or it can mutate.

Thus, anticipating Scheler, Brentano concludes that some necessary change in Being can be assumed.

God is being made, he evolves.

And in that evolution we are called to participate.

Thus, he acquires a conception of intentional being, of being as an opening to something other than himself.

Portrait of Franz Brentano taken at the end of the 19th century.M.

Wacker

Kant Scourge

For all this to be possible, Kant must be dispensed with.

Brentano will be the scourge of Kantianism, although with relative success.

In Spain, Ortega celebrates it: “the French illustration is a trivialization of Locke, the German of Leibniz”.

Brentano laments the dispersal of Leibniz, who devoted little of his frenetic activity to philosophy.

Hume woke Kant from his dogmatic drowsiness.

And Kant believed to save the knowledge of Hume's skepticism, through synthetic knowledge a priori, established in advance without being obvious.

Kant postulated what he must prove and "believed that he could build on such blind prejudices."

The Kantian hypothesis is that knowledge is regulated according to these prejudices.

Kant says: until now knowledge was regulated according to things,

now suppose that things are regulated according to our knowledge.

An unnatural, puritanical (so castrating) attitude.

Life does not demand that we proceed uniformly at all times, as mechanics does.

On the contrary, it teaches us to change our methods according to the things that come our way.

Great thinkers such as Benjamin Franklin, Darwin or Einstein himself, confessed their ignorance of mathematics, Haeckel even boasts of not knowing how to prove the Pythagorean theorem.

Mathematics knows neither the past nor the future.

He knows nothing of history, illness or sympathy.

it teaches us to change our methods according to the things that come our way.

Great thinkers such as Benjamin Franklin, Darwin or Einstein himself, confessed their ignorance of mathematics, Haeckel even boasts of not knowing how to prove the Pythagorean theorem.

Mathematics knows neither the past nor the future.

He knows nothing of history, illness or sympathy.

it teaches us to change our methods according to the things that come our way.

Great thinkers such as Benjamin Franklin, Darwin or Einstein himself, confessed their ignorance of mathematics, Haeckel even boasts of not knowing how to prove the Pythagorean theorem.

Mathematics knows neither the past nor the future.

He knows nothing of history, illness or sympathy.

Faced with Hume's skepticism, which has awakened him from his dogmatic sleep, Kant postulates synthetic a priori judgments.

Kant's remedy is worse than the disease.

But the Königsberg philosopher does not realize the weakness of his doctrine, Brentano tells us.

Instead of a priori knowledge, he should speak of a priori convictions, or better yet, prejudices.

Instead of demanding that we get rid of our prejudices, he seems to insist on them, to found his theory on objective prejudices.

It is an aberration to think that our knowledge is not determined by the nature of the objects, but that it is the objects that are determined by the nature of our knowledge.

“Synthetic a priori knowledges are something in which

we have

to blindly believe.

The existence of God, the immortality of the soul, the freedom of the will, are, instead, something in which

we must

blindly believe.

There is no evidence of its truth, we do it out of conviction.

After Kant, "philosophy has been worse than it ever was...philosophy has entered a new childish age."

Only Spencer seems to notice.

But the dominant currents of thought are locked in the Kantian dogma.

“Some professors to whom I expressed my opinion about Kant exclaimed: How glad I am to hear you say it!

It is exactly my opinion.

But it cannot be manifested."

Any philosophy that starts from Kantianism will be unable to advance.

In fact, evolution cannot be understood from Kantianism.

Huxley's Darwinism, like Lamarck's, declares that "the primary arrangement of the world seems to have a teleological character."

A character that affects both the organic and the inorganic.

There is a certain decrepitude in Kantianism,

a priori they

constitute the root of the extravagance of their successors”.

Brentano's critique could be formulated like this.

The only thing acceptable as a priori is perception and desire.

We come into the world and we already perceive and desire, we feel inclined towards certain things and feel aversion towards others.

That is the starting point, the true a priori, of any type of inquiry, that is the origin of all knowledge.

And one could go further by stating that it is sight that gives us space, and hearing that gives us time.

Neither of these two ideas are formulated by Brentano.

The first is from Leibniz, the second could be attributed to Buddhist idealism.

From a genuinely empirical perspective, those two are the only a priori acceptable ones.

intentionality

Intentionality is the central concept of the philosophy of mind.

What differentiates psychic acts from physical acts is the intentionality of the former.

Psychic acts refer to an object, lie to it.

Every psychic phenomenon is characterized by "being objectively in something", by being in some object, by addressing some object and making it the content of its representation.

For Brentano, what is decisive is the immanence of the object in consciousness.

That is why Husserl then affirms that what we call objects are always intentional objects (we know nothing about the others).

But there is something else, what characterizes the psychic phenomenon is that its object is not necessarily real.

Moreover, in itself, it is unreal.

The object of the psychic only exists intentionally in consciousness.

While the object of physical phenomena exists really and effectively.

Thought is not something closed, but continually transcends its limits and is directed towards something other than itself.

But the way of addressing and the object to which it is addressed has as much value as the intentionality itself.

Knowledge without intention is not possible.

Intention is the "act of knowing" directed at an object.

Brentano follows Avicenna and the scholastics, who have revived Aristotelianism.

Intention is a particular mode of attention (a mode of being of the knowing act) that extends its tentacles over things.

The mind is essentially intentional, and things are intentional because they tend to be.

Everything in the world is intention.

Subjects

tending to

and objects towards which

one tends

.

"understood" objects.

The “way” in which the idea refers to its object constitutes its intentionality.

There are first intentions (like “tree” or “star”) and second intentions (like “identity”, “coexistence”, “alterity”).

Logic is the science of ulterior motives.

The first intentions refer to real objects, the second to logical objects.

That is what the Christian and Muslim scholastics thought, although the Persian Avicenna is the author in whom the intention acquires the widest range of nuances.

anatomy of mind

For nineteenth-century positivism, the physical and the mental are not two different phenomena, but two ways of referring to the same reality.

All phenomena belong at the same time to the sciences of nature and those of the mind.

This was the idea of Ernst Mach, also a professor in Vienna, born the same year as Brentano, and who was allergic to metaphysics.

If we limit ourselves to phenomena, we see them in the field of our consciousness and, in this sense, consciousness is an envelope of the cosmos and every object is, strictly speaking, content of consciousness (its relations with other objects belong to the scope of a Theory of mind).

But if we consider the object in its space-time dimension, as given in the world, this object is no longer immediately present to consciousness and can be the object of physical science.

The metal and the physical are two perspectives of the same phenomenon.

But while in the mental it manifests itself immediately, in the physical through the mediation of categories such as space and time (a priori synthetic judgments, as Kant would say).

According to Brentano, physical and mental phenomena have different natures.

To justify this difference, it is not useful to say that physical phenomena are extensive, while psychic ones lack spatial location.

Nor does it serve to speak of inner and outer consciousness.

Or that some really exist and others only apparently.

What differentiates the two is the intentionality of mental phenomena.

Brentano divides psychic phenomena into (1) representations, (2) judgments) and (3) affective movement (love-hate).

Representation is the pure presence of the object in consciousness.

It doesn't matter if the object is real or not.

Dreams, hopes and fears are also representations.

Furthermore, representation is the necessary condition of other mental phenomena, hence its importance.

Nothing can be judged, desired, expected or feared, without prior representation.

Thus, intentionality (based on representations), decant judgments and, based on these, desires (acceptance or rejection).

Representations make possible, on the one hand, the true and the false, and on the other, love and hate.

The three make the feeling and the will.

Of the three, representation is the simplest of psychic phenomena.

In addition to being the foundation of the other two.

She makes judgment and feelings of love and hate possible.

If we are saddened by something, we must first represent what makes us sad.

Nor is it possible to love without judging.

Imagination plays a fundamental role in representation, as well as memory.

Brentano considers that representation is the most independent of psychic phenomena, since it only depends on its object.

Here we disagree, the representation is memory and imagination, and is not independent of the lived experiences, of the particular history of each one of the beings.

Furthermore, psychic phenomena are characterized by being conscious, by being self-evident, and by being intentionally referred to something.

We always think or reflect on something.

Although that something does not exist, that object is there, in thought, as an immanent presence.

That object can be an extramental entity or a previous psychic state.

And it will be represented, judged, loved or hated.

Brentano does not deny the existence of the external world (as some radical empiricists do), but admits that it is not self-evident, that it is mediated by perception (which is self-evident) and desire.

The existence of the external world is a hypothesis with many possibilities of being confirmed.

He seems to follow Berkeley when he asserts that perception is limited to ordinary sentients.

Its immediate object is not the trees, the clouds, or the song of the birds,

but the extensive, the colorful and the sonorous.

It is characteristic of the mental nature to be open to something different from itself, its essence is relational, to be "in relation to...".

Truth, beauty and goodness are abstractions.

What exists are good deeds, beautiful things and sincere people.

Your reality is in your exercise

Brentano unites in the same category the feeling and the will.

There is a continuous gradation between these two psychic phenomena, between pleasure-pain and the will.

Sadness yearns for something that you don't have, awakens the hope of achieving it, decides to launch out in search of it.

What was feeling is resolved into will.

There is no defined boundary between the two.

Love and hate make the will.

It has been a historical error (also linguistic) to separate the feeling from the will.

If we push this all the way through (Brentano does not) we might wonder if our individual thoughts and feelings might change the physical structure of the brain.

Since the brain is, from the phenomenological perspective, a representation,

it is conceivable that thoughts and feelings can change its configuration.

A phenomenon that is studied today in the neurosciences (although outside the

mainstream

) and is called “self-directed neuroplasticity”.

There seems to be a significant amount of empirical evidence supporting this possibility.

A fact that, if it occurred, would contradict medical materialism.

The senses only know by affirmation.

The trial by affirmation and negation.

The ascetic spirit completes the sensitivity.

"Only what has not happened does not age" (Schiller).

Every psychic phenomenon has its perfection.

Representation finds its perfection in the contemplation of beauty.

The judgment in the knowledge of the truth (which derives in the joy of knowledge) and in the love of the divine, which, as Plato taught, is the unity of truth, goodness and beauty.

The values

Values do not exist in a platonic heaven.

Truth, beauty and goodness are abstractions.

What exists are good deeds, beautiful things and sincere people.

Your reality is in your exercise.

Values do not exist in a separate world, to have reality they have to be referred to an act.

In this aspect Brentano is firm in his Aristotelianism.

The first element of moral knowledge is not the categorical imperative, nor any kind of moral apriorism, but the experience of values.

The estimation of something does not depend on our subjectivity, but has an objective nature.

Love must adjust to goodness as judgment to truth.

The subjective judgment is not the foundation of the moral act, but the nature of the object itself.

The essence of love is the evaluative act,

since the psychic acts corresponding to the phenomena of the third group (love-hate) are based on representations and judgments, that is, on the imagination and the natural appetite for the truth (although Brentano does not use these terms).

In the ideal of the sage, the path to truth coincides with the path to good.

The supreme perfection of our representative activity (of our mental culture) consists in the contemplation of beauty.

While the supreme perfection of judgment is the knowledge of the truth.

The supreme perfection of our representative activity (of our mental culture) consists in the contemplation of beauty.

While the supreme perfection of judgment is the knowledge of the truth.

The supreme perfection of our representative activity (of our mental culture) consists in the contemplation of beauty.

While the supreme perfection of judgment is the knowledge of the truth.

Creation is a divine necessity.

But creation demands contemplation.

That is why nature creates and consciousness observes.

Both are needed.

Brentano is ambiguous about the immortality of the soul (as was his teacher Aristotle).

He considers, in a very Eastern way, that souls follow an eternal path of perfection.

Who is the one looking?

Genuine, phenomenological observation also requires insight.

There is a difference between "perceiving" and "observing".

We can perceive our internal phenomena, but we cannot observe them.

They are felt, but they lack a figure (because they lack extension).

But if one succeeds in "seeing what one sees", observing one's own act of seeing, peering into the folds of sensitivity, then we are close to the teachings of the

Bhagavadgītā

.

Perceiving your own anger can make it subside.

Brentano describes this unfolding: “I see the color on the one hand and on the other hand I perceive myself seeing the color”.

While I know the thing, I somehow know myself.

"The observation of the physical, apart from making possible the knowledge of nature, can be at the same time a means of psychic knowledge."

There is a first object, the physical phenomenon, and a second object, the mental phenomenon.

Brentano identifies consciousness and mind (distancing himself from the

sāṃkhya

), but at the same time affirms that consciousness is always aware of something other than itself, with which it seems to allude to the original magnetism between consciousness and nature that this philosophy speaks of.

In a sense, Brentano is anticipating the principle of complementarity that will give quantum theory so much credit.

Where complementarity refers to the intention of the researcher when preparing his experiment.

We must insist on this idea, in our view decisive.

Color is not the act of seeing but the object of that act.

And what we are interested in observing here is the act, not the object.

Brentano, in a certain sense, denatures consciousness, distinguishes it from that other area to which it feels attracted, which is nature.

But he does not place it outside the world, but places it in each act of the conscious perception of the living being.

In this he is Aristotelian, in the first Platonist.

What we call Being is neither one nor the other, but the complementary relationship of these two spheres.

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

50% off

Exclusive content for subscribers

read without limits

subscribe

I'm already a subscriber