From the heliocentric theories of Copernicus and Newton's laws to the sequencing of the human genome and the projection and construction of the large hadron collider at CERN;

scientific illustration is applied as an art that serves not only to understand, but also to record, study, explain, project, build, catalog, communicate and disseminate.

A tool offered by the discipline of visual communication and that today continues to be one of the most precise methods we have for capturing and visualizing images or data, as it allows us to illustrate exactly what scientists want to point out, and not only capture flat data like photographs do.

It also allows you to illustrate complex concepts and abstractions (such as mathematics or physics), visualize data, reproduce biological processes,

If we stop to observe a scientific illustration we can appreciate that it has nothing to do with an artistic illustration.

You can see how aesthetics and author are left aside.

The scientific illustrator exercises the elegant and humble art of simply showing what an issuer (in this case a scientist) has to visualize, without diverting attention to any other element than the one he has to show, nor leaving his mark as an author.

If you appreciate beauty in a scientific illustration, it is because it is inherent in the nature of its model, and because of its scientific value itself.

'Young Hare', by Albrecht Dürer (1502).AD

A great and early example is that of the

Young Hare

that Alberto Dürer made in 1502, without any aesthetic element that distracts our attention from the information to be displayed.

It is necessary to emphasize that science is not only illustrated with drawings, but also represented with statistical graphs, infographics, tables and diagrams, which need to be processed by the joint work of scientific illustrators, graphic designers, scientists and science communicators.

The most perfect scientific illustration in history, for a large part of the scientific community, is the periodic table of the elements.

A table that facilitates the study, information and classification of chemical elements at a glance, and is so exceptional that Dmitri Mendeleev himself left blank spaces for elements that had not yet been discovered in his time.

On the other hand, it is also worth noting throughout the history of science the immense work of other profiles, such as that of printers and publishers when reproducing texts with increasingly complex scientific illustrations.

A great example is that of the printer Erhard Ratdolt (considered the first scientific editor in history) who, aware of the importance of representing and synthesizing mathematical examples through graphism, in 1482 produced Euclid's

Elements

for the first time in Latin, dealing with the great compositional difficulties of geometric diagrams.

Or that of the editor Johannes Oporinus who knew how to apply the refined woodcuts that had to be created to edit the

De Humani Corporis Fabrica

of Vesalius, published in 1543. Vesalius's work was the first modern anatomy, based on models of human cadavers;

the first complete study of the organs of the human body and their structure, which allowed refuting dozens of Galen's anatomical theories.

In the process of creating

Scientific Illustration: A visual history of knowledge from the fifteenth century to the present day

(Taschen) I had the great fortune of being able to document myself practically without any obstacle, with very few exceptions, to find the original documents of some of the most important scientific milestones of the history of modern science.

A fact that allowed me to search archives around the world and to be able to better appreciate the use of scientific illustrations that accompanied those documents.

However, among thousands of capital illustrations, each one important in its discipline, I would not hesitate to highlight a few.

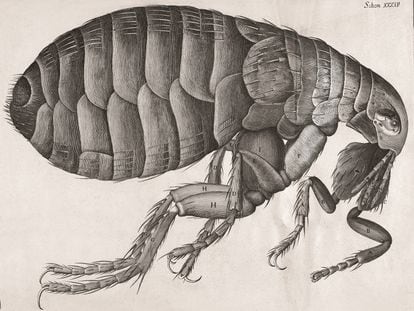

Microscopic View of a Flea, by Robert Hooke (1665).RH

I will not be very original in agreeing that the most perfect scientific illustration today is still the periodic table of the elements, due to the aforementioned.

But, without a doubt, he would also give special importance to the illustrations that Robert Hooke made in his work

Micrographia

published in 1665, the first bestseller of popular science and which coined the name "cell", citing how Hooke observed with an optical microscope the pores of a sheet of cork that reminded him of the small monastic cells of the monasteries.

Today, his illustrations of tiny bodies continue to amaze and provide useful data to the scientific community.

On the other hand, I would also highlight the illustrations of Marie Curie's laboratory notebooks, some very simple graphics that accompany the historical annotations of the first steps of nuclear physics.

It is worth mentioning that Marie Curie's notebooks are still radioactive, and in order to be able to consult them, the French National Library obliges the researcher to sign a consent as he knows that these documents are radioactive and that the BNF is not responsible for the consequences that may affect to the researcher;

and proceed to the consultation with a special suit.

And also, the ones in Alexander Fleming's notebooks with the annotations of the first records that helped discover the medical use of penicillin, one of the most important milestones of the 20th century, are very interesting.

Glial cells from the spinal cord of a mouse, Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, 1899.Ramón y Cajal

Following the branch of human anatomy, we cannot forget the great scientific illustrators of the medical discipline, such as Jan Stefan van Calcar, from Titian's studio, who made the illustrations for Vesalius's

De humani corporis fabrica

;

Nicolas Henri Jacob who made the incredible illustrations of the anatomical atlas of Jean-Baptiste Marc Bourgery in the 19th century, or already in the 20th century to Dr. Frank H. Netter, an illustrator recognized for his work for pharmaceuticals and medical publishers.

He is also the author of the illustrations for the anatomical atlases most consulted by medical students since the 1970s.

Another magnificent scientific illustration is George Lemaître's graph that represents the temporal evolution of the radius of the universe with the cosmological constant, for a space of positive curvature.

One of the first illustrations of his studies on the primitive atom (popularized as the Big Bang theory) dedicated to the origin of the universe from the point of view of quantum physics.

In this curve we can see that all the models start from a singularity (x = 0, t = 0) and how for a sufficiently large cosmological constant the universe expands.

Last but not least, I would point to the illustrations of Maria Sivylla Merian, a pioneer of entomology, who refuted that insects did not arise spontaneously from putrefying mud.

Sivylla made a series of rigorous field notebooks, providing annotations and scrupulous illustrations that led her to masterfully document the metamorphosis of butterflies.

And also the illustrations of the ornithologist and painter John James Audubon, who was a pioneer of ornithology in America, and who dedicated a good part of his career to making an inventory of North American bird species.

Cassava Root with Garden Tree Boa, Sphinx Moth, and Grasshopper, by Maria Sibylla Merian, 1702.SM

The book

Scientific Illustration...

It is conceived as a celebration of science, which visualizes the importance that it must be understandable and accessible to the general public, and that scientific illustration also plays a major role in this equation;

It precisely shows a visual journey through the history of science through the illustrations of scientific milestones as an example of what is a vital element for its understanding.

It can also be seen that many of these milestones, especially those of the first centuries of the history of modern science, wanted to reach the general public and accessible books were published, and that they never tried to lower the level of science, but rather He explained understandably.

However, scientific specialization has evolved so much over the centuries (more than 70.

000 branches recognized by the universal decimal cataloging of human knowledge today) that scientific literature is barely understood by scientists from different branches of the same discipline.

A rather serious fact that does not distance us much from blind faith.

As Carl Sagan pointed out, we should not allow science to be in the hands of a small intellectual elite, which only they can understand, since in this way we can all watch over it and also exploit its potential much further.

The art of understanding science begins with the art of communicating science.

The work of scientific illustrators becomes key so that both the general public can understand science, and so that scientists understand each other.

You can follow

MATERIA

on

,

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

Scientific illustration

Scientific Illustration: A visual history of knowledge from the fifteenth century to the present day.

Publisher: Taschen.

Theme: History of science.

Author: Anna Escardó.

Number of pages: 436.

Price: €60.

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/ZCAHDMB6WVDBPDWJ4ZUKGUMH4Y.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/AW2KNQ2UOZA4PHPLO4DEKRFIOQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/KMEYMJKESBAZBE4MRBAM4TGHIQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/EXJQILQR5QI7OMVRTERD7AEZAU.jpg)