A finding could explain why Alzheimer's is more common in women 1:07

(CNN) —

Neurologist Rudy Tanzi was still a graduate student at Harvard Medical School when he helped identify the first gene associated with inherited Alzheimer's: amyloid beta precursor protein, or APP.

"It was the summer of '86. I was 27 years old," recalls Tanzi.

"I remember thinking that for the first time since Alzheimer's Dr. Alois described amyloid in 1906, we now have a clue to its origins."

The discoveries never stopped.

Scientists around the world have continued to unravel the genetic basis of this harrowing disease that steals the mind and leaves the body empty of what it was.

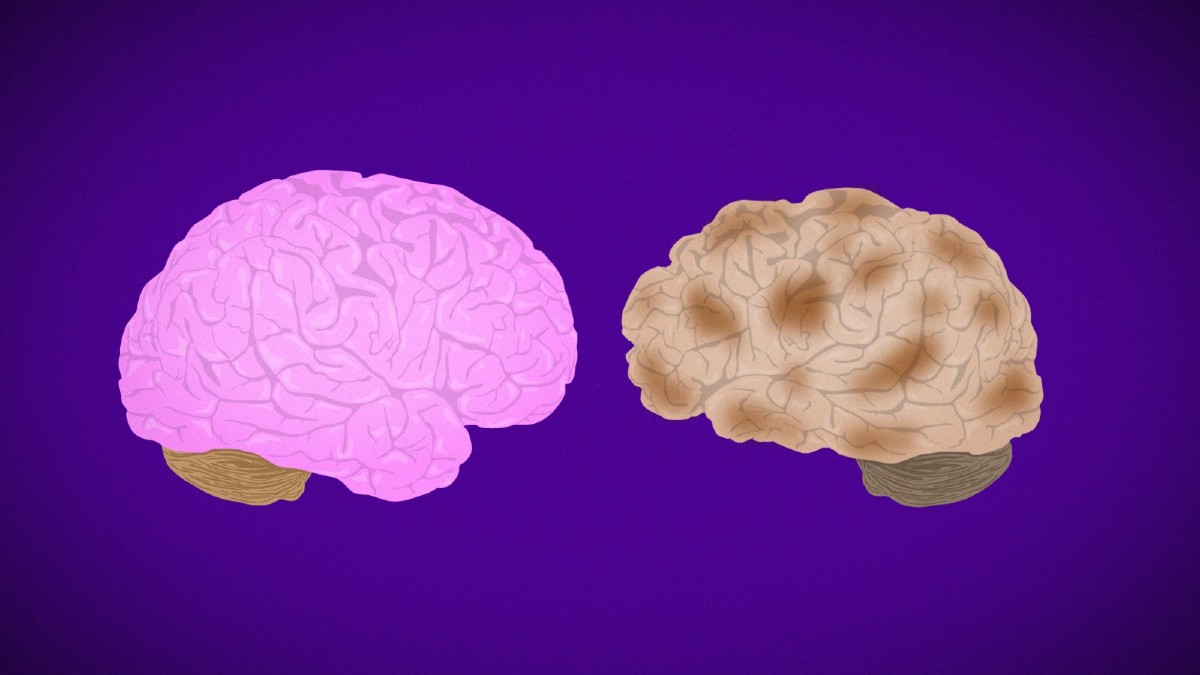

In 2022, an additional 42 genes linked to the development of Alzheimer's disease were discovered, bringing the total to 75. Shortly after that discovery, another gene called MGMT was identified, and it may explain why women have two-thirds more more likely to be diagnosed with Alzheimer's than men.

"This is a female-specific finding, perhaps one of the strongest associations of a genetic risk factor for Alzheimer's in women," study co-senior author Lindsay Farrer, chief of biomedical genetics, told CNN in an earlier interview. from the Boston University School of Medicine.

advertising

Many roads lead to Alzheimer's

Symptoms of Alzheimer's or signs of aging?

3:32

With so many genes contributing to the development of Alzheimer's disease and other types of dementia, scientists are convinced that everyone's journey may be different.

"There's a saying: Once you've seen a person with Alzheimer's, you've seen a person with Alzheimer's," said Dr. Richard Isaacson, director of the Alzheimer's Prevention Clinic at the College's Center for Brain Health. Schmidt School of Medicine at Florida Atlantic University.

“Alzheimer's disease is a multifactorial disease, made up of different pathologies, and each person has their own path.

The disease presents differently and progresses differently in different people.”

A key genetic pathway is APOE ε4, a genetic variant responsible for encoding proteins that transport cholesterol in the brain.

Having one copy of the gene puts people over 65 at risk, while having two copies is considered the strongest risk factor for future development of Alzheimer's in that age group.

But it is not a fact.

Some people with APOE ε4 do not develop Alzheimer's disease, while others without the gene may encounter the hallmarks of tau tangles and amyloid beta plaques.

Another pathway to Alzheimer's is through inflammation, "which is common to all chronic diseases," Farrer said.

Several new genes discovered this year appear to play a role in how the body's immune system clears damaged brain cells.

A boost in funding

"Alzheimer's is the only disease where a person dies twice": Latino caregivers say they face more barriers

To fuel research, federal funding in the United States for Alzheimer's research has increased sevenfold since 2011 to more than $3.4 billion annually, said Rebecca Edelmayer, senior director of scientific engagement for the Alzheimer's Association.

One research focus is finding therapies that target the immune system as well as inflammation in the brain, Edelmayer said, while other research is investigating cell metabolism and how cells use energy.

Scientists are also trying to understand more about how brain cells are connected and communicate through synapses, and "we're even seeing research looking at the connection between the gut and the brain, which is another interesting approach," he said. .

Researchers are racing to find treatment breakthroughs, aided by additional funding in recent years from the public and private sectors, Edelmayer added.

The Chicago-based Alzheimer's Association alone provides more than $300 million in funding for more than 920 projects in 45 countries.

"We want to focus on strategies that are culturally appropriate but also effective and scalable around the world," said Edelmayer.

Search for existing drugs

Another focus of the research is examining existing drugs that might prevent Alzheimer's from taking hold in the brain.

In his lab, Harvard's Tanzi uses small organoids made up of human brain cells that can develop the typical amyloid plaques and tau tangles of Alzheimer's in just over a month.

Tanzi and Harvard co-creators Doo Yeon Kim and Se Hoon Choi published a seminal article about their discovery in 2014, titled "Alzheimer's on a Plate."

42 hitherto unknown Alzheimer's genes discovered

Tanzi and his team have spent seven years testing drugs that the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has already approved on the "brain" on the plate.

Since the FDA has already verified the safety of those drugs, finding a candidate from that pool would speed federal approval of the Alzheimer's drug, getting treatments to patients faster, she said.

Tanzi also tested natural products, including herbs, spices, vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants, for their ability to affect plaques and tangles in his mini-brain creation.

"We were able to quickly screen all approved drugs and more than 1,000 natural products," Tanzi said.

"And now we have more than 150 drugs and natural products identified that could be tested in clinical trials to combat plaques, tangles or neuroinflammation."

He and his team at the MassGeneral Institute for Neurodegenerative Diseases in Boston hope to start clinical trials soon and collaborate with other scientists to see which of the potential candidates may deliver results.

"It's about giving the right person the right drug, at the right time in the course of their disease," he told CNN.

"Many people may not know this, but after the age of 40, almost all of us start to develop the initial pathology of Alzheimer's, which is amyloid plaque in the brain and neurofibrillary tangles," he continued.

"It's part of life, just as most of us start to build up a little bit of plaque in our arteries from cholesterol."

In fact, Tanzi estimates that 30 million to 40 million Americans have enough amyloid in their brains right now to benefit from a drug to reduce it, if science were able to do it safely and affordably.

"I like to say that amyloid is like phosphorous, and tangles are like wildfires that spread and spread over decades," Tanzi said.

"And along the way you're starting big wildfires, that's neuroinflammation."

By the time a person shows signs of cognitive decline, he added, "the wildfire of neuroinflammation is burning," and it's too late to significantly rescue the brain and improve thinking and memory skills.

"The elephant in the room is that we wait until the brain deteriorates to the point of dysfunction before treating this disease," Tanzi said.

"That's like saying wait until you lose half the beta cells in your pancreas before we diagnose diabetes."

One reason clinical drug trials in recent decades failed to control amyloid buildup was because many of the study participants were in later stages of the disease when "too much destruction had been done," Edelmayer said. .

"Removing the amyloid at that time was not necessarily helpful," he said.

"It's taken us some time to really understand at what point in the disease process we need to specifically target amyloid with drugs."

US Lawmakers Launch Investigation Into FDA Approval And Pricing Of New Alzheimer's Drug

Case in point: The controversial amyloid-scavenging drug aducanumab, sold under the brand name Aduhelm, has only been tested in people with mild cognitive impairment.

The FDA approved aducanumab for use in 2021 despite the fact that all but one member of an independent expert panel tasked with reviewing the drug's efficacy voted against approving it.

Although aducanumab cleared amyloid, the clinical trial only showed a small improvement in cognition in a subset of patients.

Some doctors and medical institutions across the country decided not to offer aducanumab to their patients after weighing the drug's poor performance against cost and significant side effects.

In April, Medicare announced that it would only cover the drug's $56,000-a-year cost if a person was enrolled in a study approved by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

In the same month, Biogen, the company that developed the drug, gave up trying to get the drug approved in the European Union.

In May, the company announced that it would stop endorsing the drug.

"I want to make it clear to people that in order to end Alzheimer's, we need early detection, early intervention 10 to 20 years before symptoms appear," Tanzi said.

"And what about the 6 million people in this country with this disease right now? For them, we need to put out the fire, stop neuroinflammation, stop neuron death."

lifestyle interventions

Screening tools for Alzheimer's would speed up research and help doctors find Alzheimer's cases at an earlier stage.

However, most tests today are either invasive, like spinal taps, or hugely expensive, like positron emission tomography or PET scans, which insurance companies often refuse to cover.

Newly discovered gene could explain why more women have Alzheimer's

"In the end, we need screening tools that are scalable, noninvasive, and certainly cost-effective for patients and their families," Edelmayer said.

"A blood test really is the holy grail if we can get there. We're not there yet, but we're getting close. Ask me in another two years."

Preventive methods are a key focus of much of the current research.

Lifestyle changes such as increasing exercise, eating a plant-based diet, addressing sleep deprivation, reducing stress, improving social connections and engagement, and some types of cognitive training are showing impressive results for people in the early stages of the disease process.

Keeping cholesterol and blood sugar under control early in life is also key to good brain health.

Alzheimer's does not stop a fan's passion for a team 4:59

Two recent studies in the United States have shown that such lifestyle interventions, along with medications, vitamins, and supplements, can prevent decline and also improve memory and thinking skills.

"There were actually cognitive improvements at 18 months in both women and men compared to control populations," said Isaacson, an author of the studies.

Even people who carried the APOE ε4 Alzheimer's gene, which increases the risk of dementia in later life, saw benefits in cognition, he said.

More than 25 countries are running similar multidomain lifestyle interventions as part of the World Wide FINGER network, Edelmayer said.

FINGER stands for Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Decline and Disability.

People who took part improved their cognition by 25% over two years, according to the study.

"I'm very cautious about using words like cure," Isaacson said.

"But when we use all these various tools early, during the years leading up to dementia, I think prevention is a cure. And hopefully, risk reduction can delay the pathology long enough for the person to die of something else." before he develops dementia."

All of these research approaches are "bringing us to the threshold of a transformative new era in Alzheimer's research," Edelmayer said.

"It is right now that we are facing it, especially for those currently living with the disease."

Alzheimer's

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/65WJB3EG45EZDLAF5QNRLPUDDU.jpg)