EL PAÍS offers the América Futura section openly for its daily and global informative contribution on sustainable development.

If you want to support our journalism, subscribe

here

.

The first time that Cristian Intriago, 25, saw a turtle, he found it on the shore of his beach bitten by a dog.

He was barely 10 years old but he perfectly remembers the feeling it generated in him.

“It was huge and beautiful, but they had left it horrible… I felt anger.

I needed to know more about her”, he now tells in Puerto Cabuyal, in the coastal Ecuadorian province of Manabí.

After seeing her wounded, others arrived who had been caught in trawl nets and thrown overboard.

Threats are a constant in the life of these reptiles.

"And now, on top of everything, climate change is coming and making everything even more difficult," he laments.

"I'm afraid I'll stop seeing turtles on my beach when I'm old."

That boy's anger turned to interest.

In the free school where he studied, he discussed the situation he had experienced and his desire to learn more about “these little animals” for whom survival is a huge challenge.

According to experts, only one out of every thousand specimens that manage to hatch survive to adulthood, since their journey from the shell to the shore is a real adventure threatened by various predators.

The tutors listened to his concerns and began to investigate together with the students.

“I learned fascinating things, I was very struck by how the grades defined his life so much.

I became obsessed with them”, acknowledges the young man.

Three years ago, they founded a group for the study, monitoring and protection of turtles and eggs, called Carapazón de Ninos.

Now he is the one who teaches classes at his old school.

“I'll tell you what I know about olive ridleys, tortoiseshells or greens… These guys are the future.

If they're aware that we have a lot of power to change things, they still won't go extinct,” he says.

Although he sounds convinced of it, the look of concern does not leave his face.

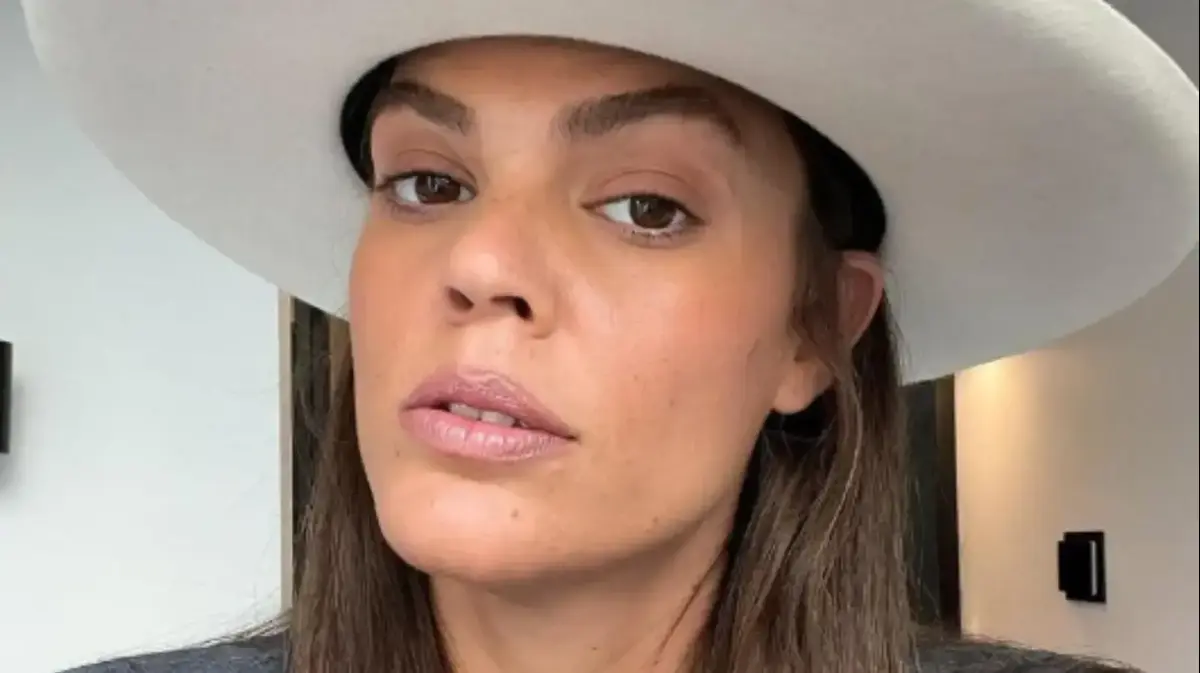

Christian Intriago teaches children on the coast of Manabí, Ecuador.Ana María Buitron

The change in temperature complicates everything: from the food they find to the danger of running out of a beach where to nest due to the rise in sea level and the very definition of their sex.

The sand in which the turtles lay their eggs acts as an incubator during the 60 days that the process usually lasts.

From the 20th to the 40th day, these eggs become thermosensitive and any climatic fluctuation will tip the balance towards one sex or the other.

The colder, the more males will come out.

And with warmer temperatures, more females.

The ideal would be 29 degrees.

This pivotal temperature would allow a balance of almost 50 and 50, with some majority of females;

an optimal scenario considering that males mate with several females and these give birth approximately every three years.

Excessive heat would cause the eggs to cook or an excess of females, as is happening in other areas such as Mexico and Central America.

In the case of Ecuador, climate change has resulted in very cold spells, rains and strong winds that have caused the turtles to take longer to nest and the fear of the environmental authorities that the litter will leave with hardly any females.

“Last year, at this point we already had nine nests, with about 100 eggs each.

Now we only have two registered.

Most likely, 90% of those born, which will be about ten, will be male.

This not only makes mating difficult.

The female turtles lay their eggs on the same shore where they hatched, some 25 years later.

“If females are not born here, they will stop arriving.

We will stop seeing them”, says Intriago worried.

Scientific evidence seems to predict this trend, although it is too early to be certain.

Shaleyla Kelez, lead biologist for WWF Peru's Wildlife program, is cautious.

"It still takes time to be emphatic, but it is undeniable that these thermal changes are going to have consequences," she narrates by video call.

“Relying on the historical resilience of turtles is not enough.

Also, keep in mind that they are 'umbrella animals'.

When you take care of them and their ecosystems, you are taking care of many other species as well.

They are key in the food chain.”

Sea turtles off the coast of Ecuador. Independent Picture Service (Universal Images Group via Getty)

One of the imbalances that would occur after the extinction of the turtles would be the increase in the number of jellyfish in the Mediterranean, since the leatherback turtles are their main predators.

Or a decrease in oxygen due to the aging of the seagrass that the green turtles would no longer consume, for example.

And extinction is not that far away.

Of the seven species of turtles, six are in danger of disappearing.

The leatherback is the one in the most serious condition, especially in the Pacific.

In the last three generations, 90% of its population has become extinct.

According to a study published in the journal

Nature

, signed by the Network for the Leatherback of the Eastern Pacific Ocean (LaúdOPO), if urgent measures are not taken, in 2050 there will be no specimen left.

In the case of the big heads, this loss does not fall below 70%.

They are the most endangered vertebrates.

"Many efforts are being made from research to protect them, but it is a huge challenge," says Kelez.

Ecuador is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world.

And a privileged one due to the presence of turtles.

Four of the five species that transit the eastern Pacific arrive here.

For Cristina Miranda, research coordinator for Equilibrio Azul, an organization dedicated to the conservation of this reptile and its ecosystems that has been in the country since 2004, we are "against the clock."

“I am concerned about sea level rise.

I fear that they will end up running out of space on the beaches to nest,” she explains.

"This is the lute," shouts a boy of about five with his face painted by a classmate.

"That's right," Cristian Intriago responds proudly, holding up a laminated poster made by the students weeks ago.

On each page, a photo of the species and its basic characteristics written with colored markers.

This species has reached the coast of Manabí.

“We have seen some and it is something magical,” he says.

The little ones are the ones who patrol in morning and night shifts to make sure that no dog or no person is disturbing the nests.

Irocco, the smallest of the group, does not miss any expedition.

“He is the first whose eyes open at 4 o'clock ″, says his mother walking towards the nests.

A baby leatherback sea turtle at Punta Bikini beach, in the province of Manabí (Ecuador). Blue Balance

There, a group of ten boys surround the fenced space that reads: “Golf species.

Estimated hatching date: 08/07/2022″.

From there, the leader of the Child Shell explains that it will most likely take longer.

“We can make sure that the dogs don't eat them.

Hopefully returning to the usual temperatures was in our hands”.