This sticker album does not exist.

Does not creak, does not smell, does not peel off.

It's an album bound together by the ethereal material of a kind of epic in vogue: misfortune.

The tragedy that surpasses the triumph to compose, beyond cold statistics, an immortal human story.

They are the cards of some eternal athletes who made misfortune —often at the cost of their health— the engine of their legend and the food for books, movies and songs, remembered in a summer without the Olympic Games or the World Cup.

Who turned adversity into lasting memory.

It's the album that won't hit the newsstands this summer.

But when the neon of temporary victory loses its glow, when the honor rolls are covered with dust and oblivion, these cards will continue to shine in that corner that transcends victory: immortality.

Raymond Poulidor

The eternal second.

The myth of defeat.

The French cyclist of the 1960s and 1970s competed in the Tour de France 14 times.

In his

purple Mercier

jersey with yellow sleeves, Raymond Poulidor,

Poupou,

was the crowd's favourite.

“

Allez Poupou”

, the public yelled at him wherever the cycling epic was taking place: in the ditches and in the stories of the books.

The last one, this summer —and there are already a dozen despite being a second—, is

Poulidor anyway!

, by the writer and poet Christian Laborde.

His simplicity, his rural origin and the charisma of his smile aroused popular fervor.

Every summer, humble France sighed to see his dream come true: to see his idol with a wide face and rustic features arrive in Paris, dressed in yellow.

It would be the victory of the people.

However, that dream was shattered every year by his nemesis: Jacques Anquetil, the boy king, the cold and distant and elitist dominator of the Gallic round.

Jacques Anquetil and Raymond Poulidor push up the Puy de Dôme in the 1964 Tour de France.DIARIO AS (DIARIO AS)

That giant was replaced by another: the cannibal Eddy Merckx, winner of another five Tours that wiped out Poupou's chances.

And so, sandwiched between two myths in cycling history, Poulidor was never able to win the French round.

He climbed eight times on the podium in Paris: three second places and five times on the third step.

But he never won.

He did not even wear the yellow jersey

for a single day,

worn by almost three hundred cyclists in history.

Once, in 1967, he fell just six seconds off the lead.

Once again, in 1973, he lacked eight tenths of a second to put on the symbolic

jersey.

Less than a second.

But it could not be.

And that eternal defeat, the eternal misfortune disguised as a fall or failure, earned him immortality.

“If I had won a Tour no one would remember me”, Poupou repeated many times.

He was right.

Time would have erased the memory of him, something he deeply feared because it was his only legacy in the absence of a great record.

Instead, today, his name is already a metaphor.

Being a

poulidor

means being second, or worse: second.

In his autobiography in French, entitled

Champion!

, the final pages brim with emotion.

They relate the last day that Poulidor met his historical rival.

He was in a hospital room in 1987. Anquetil had just had his stomach removed and, at only 53 years old, he was on the verge of death.

It was time for his farewell.

And Anquetil, the winner, told him: “I'm sorry, partner: I've already told you many times and I'll repeat it: this time you'll also arrive behind me, as usual.

But it's better for you.

I always envied you, you know?

Poulidor, the loser, the cyclist who made defeat the basis of his

poupoularité

, lowered his gaze so that his old enemy Anquetil, now his dear friend Jacques, would not see him cry.

Three years ago,

Poupou

passed away at the age of 83.

L'Équipe

published a special supplement and headlined it on the cover: “The Eternal First”.

Eternal glory to Poulidor.

Moacir Barbosa

Who remembers an old doorman?

In general, hardly anyone.

In Brazil the answer is different: everyone remembers Moacir Barbosa.

Juan Villoro described him as the goalkeeper who died twice.

The second death holds no mystery: on April 8, 2000, a man who had borne a heavy shadow his entire life died of a stroke at the age of 79.

The first death, caused by that shadow, happened fifty years earlier, in the Maracana stadium, in the World Cup final that Brazil had to win against Uruguay.

And to understand it well you have to go to a fundamental book:

Barbosa.

A goal silences or Brazil

, by the journalist Roberto Muylaert.

A classic that transcends football.

It was three thirty-four minutes in the afternoon of July 16, 1950. The Uruguayan announcer Carlos Solé narrated it this way on Radio Sarandí: “Pérez advances, he crosses the ball to Ghiggia.

Ghiggia escapes from Bigode.

The fast Uruguayan right winger advances.

Ghiggia is going to shoot, shoot… Goool, goool, Uruguayan goal.

Ghiggia threw violently and the ball escaped Barbosa's controller.

At 34 minutes, scoring the second goal for the Uruguayan team”.

The 200,000 spectators (200,000!) fell silent.

A paralyzing cold ran through Barbossa's body.

The entire country fell silent, cried and blamed the national disgrace on that 29-year-old black boy.

That goal ruined Moacir's life.

He never returned to the national team.

His football career declined.

He was singled out on the street.

Blamed for the saddest day for a country.

He had to live as an employee who cut the lawn of that Maracanã where he died for the first time.

He didn't care if he kept repeating a phrase: “I'm not guilty.

There were eleven of us”;

the sentence was already pronounced.

Legend has it that, as an employee of the field, they gave him the old goal where the goal fit.

And that he burned the wooden sticks.

legends.

The truth is that he could never bury the ghosts of him.

Not burn them.

Little more than thirty people attended his funeral.

The Uruguayan singer Tabaré Cardozo dedicated a song to the goalkeeper.

It's called

Barbosa

and it has a great stanza: “Burn the sticks, Barbosa, from the Brazilian goal.

The sentence of Maracana is paid until death”.

So it was.

With a nuance: nobody remembers the name of the goalkeeper of that champion Uruguay.

Moacir Barbosa's yes.

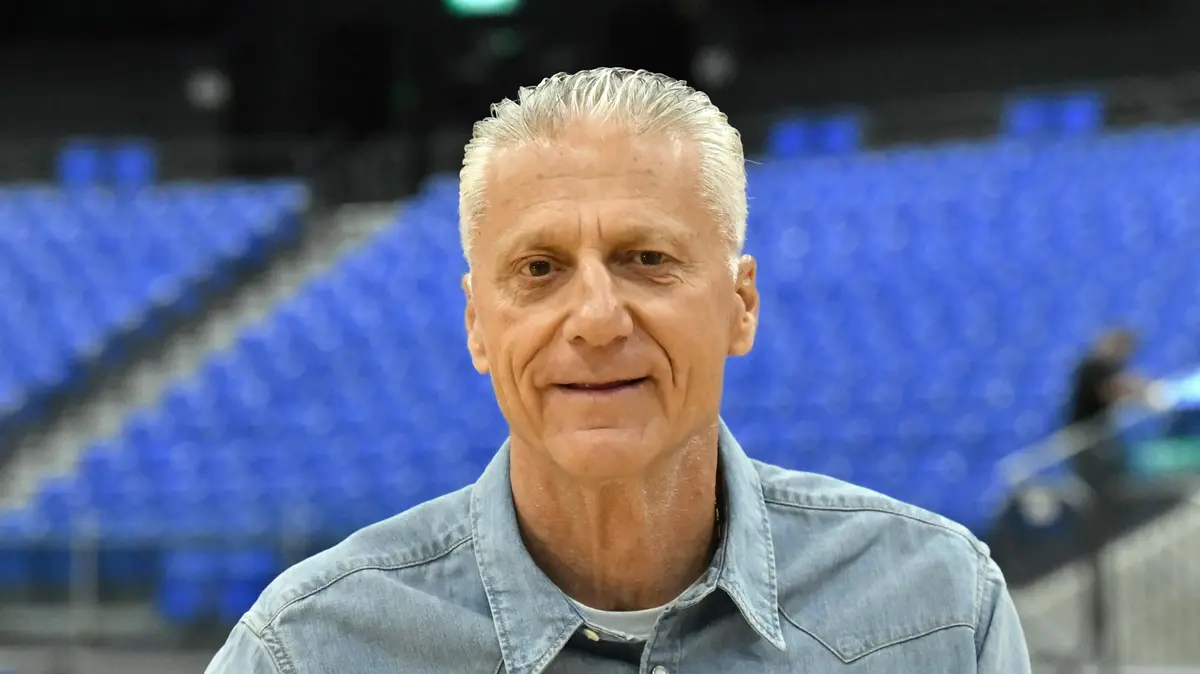

Elena Mukhina

The word is not eternal glory.

Memory yes.

The memory of Elena Mukhina, a reflection of a brutal world, will never be lost.

The Soviet gymnast was the hope of the USSR to recover the Olympic scepter in Moscow 80 - her Olympics - and reduce the 10 of the Romanian Nadia Comaneci in Montreal 76 to an anecdote, to the greater glory of Ceausescu.

Every communist dictator had his gymnast, his future broken toy.

The USSR had Elena Mukhina: petite, blonde, shy, blue eyes, a graceful caged bird, a smile whose sad corners always contain bitterness for that alcoholic father who abandoned her as a child and that mother who died in a fire when she was five years.

Elena Mukhina, at the 1978 world championships. Universal (Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

Gymnastics was her home.

The Moscow Olympics were drawing near.

The big date.

There were only two weeks left.

The pressure was enormous.

And there were two terrifying words in his mind: Jump Thomas.

Go to YouTube and type those two words.

He will be scared.

It was a very dangerous element introduced in the men's floor exercise two years before.

No woman had ever done it.

It put the body at maximum risk: the slightest mistake could make you hit the ground on the chin or the back of the head.

But her coach, Mikhail Klimenko, almost a father in his sudden orphanhood, insisted.

He insisted even though Elena was injured.

She had not been allowed to heal properly from her broken leg.

She had to train to get to the Games.

She had already done it five years before: training after breaking her ribs, suffering a concussion and having swollen joints.

It was July 3, 1980. Elena, weak from weight loss and with her leg still injured, was training in a Minsk pavilion.

It was time to execute the Thomas Jump.

She did it.

And she smashed her chin into the ground, broke her spine and left her quadriplegic.

She was twenty years old.

She was never able to get out of the wheelchair again.

The USSR covered up the accident for more than a year: nothing should obscure those Games.

“Everyone knew I wasn't ready for that jump and they kept quiet.

No one stopped to say stop.

I had said more than once that I was going to break my neck doing that element.

He had hurt me a lot several times, but he [his coach Klimenko] would only answer me: 'Gymnasts like you don't break their necks,'” Elena recounted later.

The future heroine was forever in a wheelchair.

She couldn't say, like Simone Biles, I don't go out and compete.

That was the Soviet Union.

By the way: another Soviet gymnast won the all-around at the Moscow Games ahead of Comaneci.

The Soviets also won as a team.

They celebrated it.

Instead, Elena Mukhina would spend twenty-six years a quadriplegic.

She passed away in 2006, at the age of 46.

Thomas Jump is already prohibited.

But his tragedy - replete with teachings on the brutality of elite sport controlled by totalitarian regimes, on the outcome of fragile puppets in the hands of soulless puppeteers - is, unfortunately, immortal.

The strange thing is that there isn't a movie of his or hardly any books.

In Spanish, only an eBook booklet:

Elena Mukhina, Olympic champion

, by Alberto Capra.

paul morphy

Portrait of Paul Charles Morphy published in 1859. UniversalImagesGroup (Getty Images)

The mysterious.

The romantic.

The eternal myth of 19th century chess that sways between epic and tragedy.

The protagonist of a recent movie available on platforms:

The Opera Game

.

This New Orleans wunderkind was 21 years old when he crossed the Atlantic.

He longed to face the best chess players in Europe.

He was accompanied by an aura of an intuitive player and a lethal artist.

And he did not fail: in London and Paris he defeated the giants Lowenthal, Harrwitz and Anderssen, and though he could not get Howard Staunton out of his cowardly hiding place to accept the challenge, all took the American's superiority for granted.

Paul Morphy, the best chess player in history: this is how he was invested in Paris in 1859. Triumphant, Morphy returned by ship to the United States and challenged all the masters of his country to face him with a pawn advantage and making the first move.

No one wanted to accept such humiliation.

And Morphy chose to leave the game.

The acclaimed champion left chess and became a lawyer.

Frustrated by a failing legal career and fed up with everyone constantly telling him about the 64 squares, Morphy developed a raging animus against the game that had occupied his life.

A pathological phobia.

A mental problem.

He would not tolerate anyone in his presence uttering the damn word:

chess

.

He grew surly, introspective.

He locked himself in with his looping obsessions.

Paranoia slowly consumed him.

And he died in a bathtub at the age of forty-seven.

It was the origin of the legend of him.

Chrome without crown

The Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid has published a curious little book.

It is titled

Glossary of Failure

, edited by Valerio Rocco.

In it, a dozen authors —mostly philosophers— reflect on the matter.

Fall, defeat, disaster, decline, oblivion: all the faces of failure.

Why exalt a type of syrupy failure stripped of its true hardness?

Why is success enthroned and failure hidden?

However, therein lies the failure: pumping eternal memory.

The Dutch

clockwork orange

and its lost World Cup in 1974 against Germany, and then in 1978 against Argentina, and then against Iniesta's Spain in 2010, without ever sewing a star on its

oranje

shirt .

The eight NBA finals lost by Elgin Baylor with the Lakers without ever winning a ring (until the Lakers won the title the same season that Baylor had retired due to injury).

The impotence of the British Formula 1 driver Stirling Moss, four times in a row world runner-up and three consecutive times in third position.

The Ferrari Scaglietti was driven to victory by British Formula 1 champion Stirling Moss at the Cuban Grand Prix in 1958. In the 1980s the Ferrari Scaglietti returned to Modena for restoration.Rickard Bruzelius

The invariable defeat of the Kenyan athlete Paul Tergat, always behind the Ethiopian Gebrselassie as second classified: second in the 10,000 meters in Atlanta 96, second in the world championships in Athens 97 and Seville 99, and second in the Sydney 2000 Games.

Pilotari Genovés II, five times individual runner-up in pilota valenciana despite being a legend of the hand ball game without the

red belt

that distinguishes the champion.

The Soviet chess player Víktor Korchnoi, triple runner-up in the world, ten times candidate for the title and uncrowned king of the board, like Paul Keres or Efim Geller.

The defeat at the South Pole of Captain Scott, second behind Amundsen in a loss that cost him his life.

All of them, broken cards at the time, today continue to project the immortal light that brings them closer to any mortal.

The one to arrive, to see and to lose.

50% off

Subscribe to continue reading

read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/P4P3GJOGGRGGTMT2ZGCZQRX7SE.jpg)