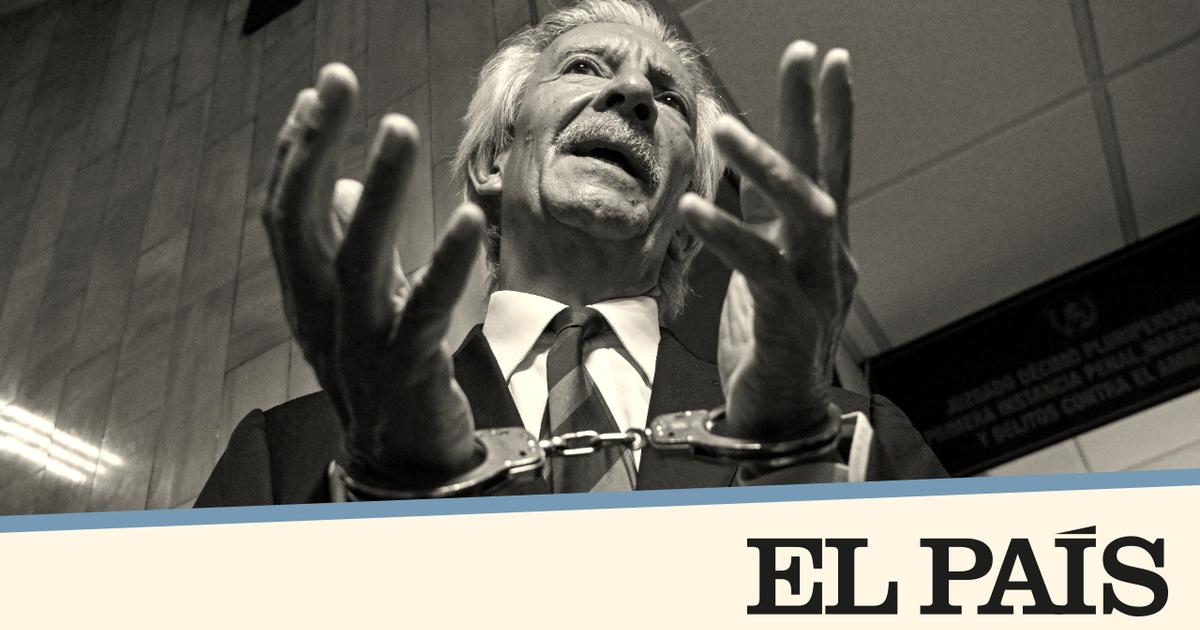

A group of Sudanese recovers in Oujda after jumping the border fence with Algeria. Javier Bauluz

Hamza's house is in a cul-de-sac near the Oujda souk.

The door is almost always open because the only key is the landlord.

The air thickens as you climb the first ten steps to the first floor.

The house has two floors, a roof terrace, a bathroom and ten rooms with rusty walls.

When it rains the water enters through the skylight of the stairs.

There is no kitchen.

Not furniture.

No luggage.

Just some mats and mats stuck to each other and a couple of mobiles charging in the sockets.

Sleeping here, on a piece of land, costs one euro a day.

The house of Hamza, a twentysomething and enigmatic Sudanese, serves as a hiding place for 40 Sudanese refugees who have just arrived in Oujda, the Moroccan city just five kilometers from Algeria that is the penultimate border before trying to jump to Spain.

Oujda has half a million inhabitants and is the main gateway for irregular immigration to Morocco.

Here are those who sooner or later will try to jump the fence of Ceuta or Melilla.

Or if they can afford it, go to the Atlantic coast to embark on a boat to the Canary Islands.

Some men and women arrive here so broken, so raped or tortured that they will give up their dream of reaching Europe.

They will settle in any Moroccan city where they find work.

Very few, exhausted from trying, will return to their countries.

Others will die trying.

Many of the occupants of Hamza's house have lived in refugee camps in Sudan.

They have also passed through detention centers in Libya.

Some show the scars caused by the burning plastic falling on the skin, one of the favorite tortures of Libyan militiamen - although not the most twisted.

They planned to reach Italy or Malta in a rubber boat, but changed the route as thousands of Sudanese have been doing in the last two years: in Libya, the mafias increasingly demand more for less.

More information

Massacres in Melilla and Libya: nothing new on European borders

Hamza speaks for the first time and everyone is silent: “Before, for 500 euros you had two attempts to get to Europe by boat.

Now the price has gone up and if you don't get it the first time you're left with nothing.

The inflatable boats are much worse and when the [EU-funded] coastguards find you at sea they hand you over directly to the militias.”

Babakar Ibrahim, another of the tenants, adds: “The militias have a big business.

You no longer go through a single prison where they ask your family for money to free you, now they send you from one place to another and ask for several ransoms.

For these Sudanese —and the rest of the nationalities found in the city— the road to their destinations, whatever they may be, today passes through Spain.

When they heal from their wounds.

When they rest.

When they have enough money to continue the trip.

A young migrant shows the X-ray of his feet, fractured after crossing the border fence between Algeria and Morocco, in the border city of Oujda.

Javier Bauluz

On the quick trip to the roof, dozens of documents from the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) are seen lying on the floor of a room with the UK flag painted on the wall and a bag with two hooks of those used to hold on to the fences of Ceuta and Melilla.

The tenants are not very happy with their rent in this filthy house.

“The landlord cuts off our water so that we don't spend money.

He is not a good guy, ”they say.

But there isn't much to choose from here either.

In the streets, bridges and mountains of Oujda sleep dozens of young people and minors who cannot even afford that euro a day.

Hamza's landlord suddenly appears on the terrace.

He is a man in his early 30s, tattooed and stocky, wearing a tight T-shirt.

He runs a women's dress stall in the souk and always has an eye on his other business, the most profitable.

He himself authorized the visit of EL PAÍS to the house when the Sudanese consulted him, but he does not trust it.

He doesn't say anything, but by his mere presence everyone understands that the conversation is over.

The center of Oujda is full of cafes where men spend hours sitting on the terraces doing nothing.

The intense traffic breathes at traffic lights where sub-Saharan women stand begging for money with their children, also hoping to reach Europe.

At a crossroads a little further from the center, a Syrian refugee dressed in black tells with a poster that she has been stranded in the city.

A square with grass and towering palm trees opens the way to the walled medina, where she bustles with a souk full of clothes and a neighborhood that chats on stools in front of the doors of their houses.

“There is no safe place here”

During the Feast of the Lamb, the most important date in the Muslim calendar, which this year has fallen on July 10, it is extremely hot and there is no one in the street.

At noon this journalist's phone rings.

It's a message in Arabic from one of the boys at Hamza's house.

-You are going to come?

"Do you have a safe place to meet us?"

“There is no safe place here.

The appointment rushes into a corner where more than 30 young people appear.

The group knows this street well.

Here is the tiny, low-ceilinged place where many of them eat every day.

It is run by Mohamed, a 64-year-old man with gray hair, a three-day beard and arched eyebrows.

The boys call him

hach

, a formula for addressing older people with respect.

Mohamed has lost his regular clientele since his shop filled up with Sudanese a year ago.

At the price of one euro per person, he prepares enormous pots of lentils with bread or peas that the boys mash with a glass coke bottle that serves as a mortar.

“Sometimes they don't have money and ask me for credit.

I know they will never pay me, but what do I do?

Do I leave them hungry?

I do it altruistically, I know what they are going through: my own son wants to emigrate”, he explains.

The safe place to talk ends up being a nearby coffee shop with air conditioning and surveillance cameras.

A first group of five people enters, in which there are two boys of 13 and 14 years.

They are those who do not have the euro a day to pay for a house and sleep on a plot full of rubble where not long ago there was a building.

On the stones are sleeping bags, filthy mattresses and a tent that houses 13 other refugees.

A few meters away it smells like a dead cat and fermented garbage.

The two teenagers, Mohamed Ibrahim and Adil Adam, tell similar stories.

Poor family, war, deaths, failure in studies.

They left Sudan when they were just 10 years old together with other boys.

And only they remain.

His plan is to get to Spain.

"Does anyone take care of you because you're little?"

— Here everyone takes care of himself.

The next appointment is with Hamza, in the same cafeteria, at six in the evening.

But he, who hates being late, is late for more than 40 minutes.

He greets without shaking hands.

His Islamic morality, he will say later, does not allow him to touch women.

— The landlord has locked us up and I couldn't come before.

The man decided that that day he would go to collect his daily rent first.

He kicked out those who couldn't pay him and locked up those who did.

His particular way of avoiding anyone sneaking up on him.

"I don't know why he did it, don't ask me, but it's our freedom under his control," Hamza is outraged.

The young man wants to help.

He has facilitated interviews with his countrymen and spent a couple of hours explaining the frustration of being a refugee who cannot find a safe place to live.

“Arriving in Oujda is a reality check.

Many are not aware of how difficult it is to continue if you do not have the money to do so.

After what we've been through, it might be a safer place, but there's no work for us here.

What would you do?

Well, keep moving,” he explains.

A 16-year-old Sudanese boy who broke his foot upon arrival in Oujda, on the Algerian border with Morocco. Javier Bauluz

Oujda was prosperous and dynamic, despite facing a 1,500-kilometer border that, in the last half century, has been closed longer than open.

She lived off smuggling.

The city has been one of the great harmed by the hostilities that mark relations between Morocco and Algeria.

With the definitive closure of the passes in 1994, vigilance increased and its decline began.

And it radically changed the profile of those who began to walk its streets.

Oujda always received foreigners.

In the 1960s, the city became the second in the Moroccan Kingdom with the most foreigners.

More than 28% of its neighbors were immigrants, according to data compiled in a book by geographer Abdelkader Guitouni.

They were, above all, Algerians, Spanish and French.

The university today attracts hundreds of Sub-Saharan students,

at the same time that Oujda is the first city that 41% of migrants set foot on when they arrive in Morocco, according to the national statistical institute.

The vast majority, clandestinely.

Violence and kidnappings at the border

To get to Oujda you also jump over a fence.

And a moat.

Xavier, a 30-year-old doctor from Chad who attends the city's emergency service, dedicates a large part of his consultations to treating the wounded on this border.

Amputations of fingers in winter due to prolonged exposure to cold and fractures of the foot, hand, leg, head or maxilla throughout the year.

According to the testimonies of his patients, "many of the fractures are due to the aggressiveness of the armed forces on the Moroccan border."

The police are not the only threat.

Terrible stories circulate here about what can happen to you if you don't run long enough once you've gotten over the barbed wire that separates Algeria from Morocco.

“When you enter you have to run away from the mafia.

If they hunt you down, you end up locked in a house, they don't feed you and they don't release you until your family pays," says Hamza.

These kidnappers, who imitate the Libyan model of extortion of migrants, are Moroccans in cahoots with Algerians who, from the other side, notify when a group passes, he assures him.

Alan, a priest of Spanish-French descent born in Oujda 70 years ago, recounts with concealed enthusiasm how years ago he assumed the role that the authorities did not exercise.

“We found out the hiding places where they were locked up and we got them out of there.”

The houses continue to exist in the same poor neighborhoods of the city, very close to the border.

In addition to police brutality and kidnapping, there are other ways to end badly at the border.

When crossing, the migrants go to the so-called taxi-mafia that bring them to the city gates for 50 euros.

They go at full speed and run a very high risk of accidents.

The doctor especially remembers three of those victims who have become paraplegics.

Two of them live in the only Catholic church in Oujda, the only institution that has offered to serve them.

The third has been in the hospital for two years.

Dr. Xavier talks with one of his patients who became a paraplegic due to an accident at the border.

/ JAVIER BAULUZ

Xavier warns that migrants in an irregular situation – those who have not even obtained a paper from UNHCR that recognizes them as refugees, those who do not have a passport or residence permit – are denied treatment.

“There is a reality here that Morocco ignores.

It is our duty to provide assistance to a person in danger, there can be no differences”, claims the doctor.

It is the night before the Feast of the Lamb, the shops have closed and everyone is already at home preparing for the celebration.

Hamed Mahamad Abded, covered in a thin layer of orange dust, sore and in ripped jeans, finally arrives in the city.

He just jumped the fence and escaped from the mob.

He asks for refuge in the church.

They give it to him, but it will be brief: the capacity of the priests only reaches to attend to the most seriously injured and the children.

The 21-year-old boy, also from Sudan, thinks only of changing his clothes.

"My story is long and quite sad," he announces.

Hamed's four brothers were killed in 2015 by militiamen from a rival ethnic group who invaded and burned his village.

He was only 15 years old.

He was saved because he was studying in Niala, the capital of the dangerous Darfur region.

A year after the event, he left.

The young man went through illegal gold mines in Chad, spent more than a year kidnapped and enslaved in Libya and was arrested twice in Algeria.

His body is full of scars.

Some look like the ones the other boys show, the plastic ones melted into the skin.

Hamed says that he does not want to go to Europe if he finds a job in a tile factory in Morocco.

He claims that he knows the trade, that he learned it from one of the Libyans who held him hostage.

If he doesn't find it, he won't come back either:

“After all the terrible things that have happened to me, life means nothing to me.

Not even if they gave me all the gold and silver in the world would it compensate me.

But if I were deported to Sudan, I would do it again."

Hamza does want to get to Spain.

He hopes to do it legally, although there are no options for him.

In the best of cases, the Spanish embassy could make an exception, as he is occasionally doing with some Afghans, and offer him a safe-conduct to request protection in Spain.

The asylum law contemplates that option, but it is hardly applied.

Hamza has to find another formula.

Meanwhile, he regrets wasting time in Oujda.

He does not know when he will leave this tortuous place where there are people who, even knowing what is happening here, prefer not to appear in this report.

It's not indifference, it's fear.

50% off

Subscribe to continue reading

read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/4VKCNYKUVRMHDATJ3YEUU2UQUU.jpg)