In the well-known film

Dances with Wolves

(1990, Kevin Costner), its protagonist, a lieutenant in the Union Army, befriends an old Sioux (in the book on which the film is based, he is a Comanche), who teaches him the helmet of a Spanish conquistador, while he tells him that "those who brought it arrived at the time of my grandfather's grandfather" and were eventually expelled, thus giving Hollywood the impression that for centuries there was no continued Spanish presence in California, Florida , New Mexico or Texas, or that the indigenous people defeated the peninsulars settled in the West of the current United States.

It is difficult to concentrate so many falsehoods in so few minutes of tape.

More information

The Spanish black legend that Hollywood has spread

Four centuries before John Wayne never left an Indian alive on movie screens, Buffalo Bill made bison an endangered species, or General Custer entered eternity shooting wildly, Francisco Vázquez Coronado had already set foot in what are now Texas, Arkansas, Utah and New Mexico, discovered the Colorado Canyon and soaked his shattered feet in the Rio Grande.

Forged at the border.

Life and work of the explorer, cartographer and artist Don Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco in the Great North of Mexico

(Desperta Ferro Ediciones, 2022), by John L. Kessell and Javier Torre Aguado, recreates the incredible and little-known history of the Spaniards of the 18th century who maintained and explored the limits of the Hispanic empire in what is now the North American Southwest.

Harassed by the French soldiers who entered from Louisiana, suffering the lurches that the policy of international alliances marked at all times, facing bellicose Indian tribes armed by enemy powers and trying to spread Christianity among Apaches, Comanches or Gilas, a population of 17,722 Spaniards defended and expanded the northern border of New Spain.

And they got it.

The northern limit of New Spain included a dozen forts, called presidios in those days, that rose in a horizontal line, from east to west, from the Gulf of Mexico to the Sonoran desert, some 600 kilometers from the Pacific.

In each of these isolated forts, hundreds of kilometers from each other, lived half a hundred soldiers who tried to feign the illusion of a protected border.

Among all the settlements, two stood out: Santa Fe and El Paso.

The latter included a fort, five missions, and numerous ranches, haciendas, and farms scattered around it.

But in 1680, Santa Fe was destroyed by the Indians, which caused a massive influx of refugees to El Paso.

“Overnight, El Paso was transformed into a community taken over by those fleeing, a kind of colony in exile,”

The arrival of settlers and soldiers in New Mexico was constant during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, among them was, in 1730, Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco, "virtually unknown in Spain, but who was one of the most versatile and fascinating figures of Hispanic America”, as defined in the essay.

Miera, a self-taught artist trained in the mountains of Santander, painted and sculpted works of art that adorned – and continue to decorate – colonial churches and missions.

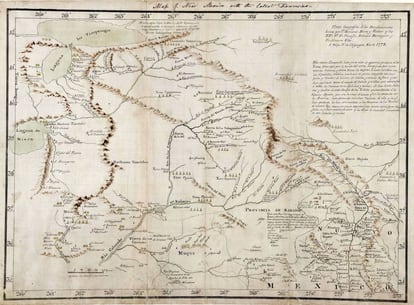

But he was also an engineer, militia captain, explorer and cartographer, making one of the "most relevant and precise maps of the northern border of the 18th century."

When the Cantabrian arrived in New Mexico, 25% of the population was already mestizo.

“The Indians who lived on the outskirts of the capital actively participated in the urban and commercial world.

Many of them spoke Spanish, dressed in the Spanish style and consumed Spanish products if their finances permitted.

As Britain, France, and Spain contended elsewhere across the globe, the empire's far northern frontier braced itself for any [Indian, French, Russian, or British] invasion.

The Crown, under the majesty of Ferdinand VI (1746-1759), wanted to have a precise knowledge of the extension of its territories and to know the exact location of the borders, for which it was necessary to have reliable maps”.

Miera was in a position to offer her services and capture the Viceroyalty of New Spain on a large plane,

Bernardo de Miera's 1778 map showing northeastern New Mexico. US Library of Congress

Thus, in 1747, Miera was part of an expedition against the Apaches, with an army that rode "with a curious appearance."

More than a military formation, it seemed like a fairly informal gang.

They did not wear a uniform, nor did they carry regulation weapons.

Each soldier wore his usual clothes and fought with the same pistols or arquebuses that he kept in his house to defend his home from possible assaults.

The official weaponry of the few who owned it consisted of a long steel-tipped spear, a short sword, and a single-shot shotgun, which took almost two minutes to reload.

The Cantabrian, meanwhile, was taking note of all the places where they passed.

The military operation failed, since they did not find the Apaches, but the cartographer did manage to draw the first map of New Mexico in 1748.

In 1752, peace came with the Comanches, who would be allowed to participate in trade fairs held in Taos and Pecos, Texas.

Everything prospered.

In fact, in 1758, Miera drew up a new map of the Santa Fe region, where he already accounted for 16 communities and three villages, in which 5,170 Hispanics, 225 captive Indians and 8,694 free Indians lived.

El Paso, for its part, was inhabited by 2,568 Spaniards and 1,065 Indians.

In total, the number of men capable of defending the province, between the ages of 15 and 70, was 5,294 men.

For their part, the allied or Hispanicized Indians, who were integrated into the troops against Apaches and Comanches, had 48 muskets, 17 pistols, 82,000 arrows, 802 spears, 103 swords, 4,813 horses, 193 leather jackets (the

bulletproof vest

of the time), 8,325 heads of cattle and 64,561 sheep.

On August 4, 1760, a devastating Comanche attack took place.

“Waves of horsemen at a full gallop, painted in bright colors, heavily armed and uttering deafening shouts and howls, arrived at Taos, which, in its brave defense, resembled those walled cities with bastions and towers that they paint for us in the Bible.

In their wake they razed many of the scattered ranches.

The terrified farmers and their families sought refuge in a fortified house.

The Comanches razed the hacienda and killed a few women who were fighting like men, and once they were dead, they insolently joined them with the dead.

56 women and children were taken as captives”, Miera wrote.

In 1777, Comanches and Apaches waged a merciless war with each other, with a clear Comanche advantage.

"They have stripped the nation of the Apaches of their lands, taking control of all of them, cornering them to the borders of the provinces of our king," wrote the Santander native.

That year, a new expedition was organized to try to connect El Paso with the Pacific.

The Spanish arrived at Great Salt Lake (Utah), where they did not run into the Comanches, but the Timpanogo and Laguna tribes.

“Currently, the Laguna-Timpanogos Indians on their official website recall without any rancor the meeting of their tribe with the missionaries [they always went religious on the expeditions].

There were moments of great tension and confrontation, but everything was resolved happily," the book recalls.

The final confrontation with the Comanches did not come until September 2, 1779, in Colorado.

Generals Juan Bautista de Anza and Cuerno Verde were going to measure their forces.

Both had lost their respective fathers in previous attacks.

There was something personal.

The Spanish won.

According to Anza's diary, in addition to Cuerno Verde, his eldest heir also died, so that the cycle of intergenerational revenge had ended.

This put an end to the combative trajectory of Cuerno Verde, "a cruel scourge of this kingdom that has exterminated many peoples with hundreds of deaths and prisoners who have later been sacrificed in cold blood," said Miera, who participated in the battle.

In the place where the fight took place, Interstate Highway 25, these events are commemorated every year.

But after 35 years of constant struggle, during the reign of Carlos III, everyone was tired of so much "violence and blood."

On February 25, 1786, in Santa Fe, the Indian and Hispanic leaders signed peace.

Aza embraced, one by one, all the Indian chiefs.

“From that day on, Hispanics, Comanches, Pueblo and Yuta traded without hesitation and made sure that there were no economic abuses in the transactions.

In addition, the Comanches made peace with the Yutas.

The Navajos joined a month later.

The alliance with the Navajo, Pueblo, and Comanche included facing a common enemy, the Apache.

But in August 1786, the Apaches, Ckonens, Mesclaros and Mimbreros also joined the peace agreement with the Spanish.

“The Comanche and Apache peace was the greatest success on the frontier for more than a hundred years.

It was not simply a military and diplomatic success, but it was a success of all the peoples who signed the agreement and allowed decades of relatively stable relations between all of them”.

Then came the independence of the United States and Mexico and the war returned.

In 1976, during the celebration of the centenary of the formation of the state of Colorado, the Hispanic population chose Miera as a "representative figure" and immortalized him in a stained glass window that adorns the Colorado Capitol.

The committee's spokesman, Chicano artist Carlos Santisteva, stated that "Don Bernardo will long remain a source of pride for all Hispanic and Chicano people."

Years later, Kevin Coster appeared on the big screen chatting with an Indian who told him that he kept a helmet that his grandparents' grandparents had taken from a Spaniard.

He did not tell him anything about the peace between the Indians and the Spaniards, nor did he mention the warrior Geronimo, who spoke Spanish, the same language as the inhabitants of Santa Fe, El Paso, Taos and Pecos, a language he shared with Bernardo de Miera. and Pacheco.

This is how history is written in Hollywood.

look for it in your bookstore

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.