Jean-Michel Delacomptée, novelist, essayist and academic, notably published “Our French language” (Fayard, 2018), Grand Prix Hervé-Deluen from the French Academy. He is also the author of remarkable literary portraits, in particular of Montaigne, La Boétie, Racine, Bossuet and Saint-Simon, often published in the prestigious collection "L'un et l'autre" by J.-B. Pontalis at Gallimard. Latest work published:

Cabale à la cour

(Robert Laffont, “Les Passe-Murailles”, 2020).

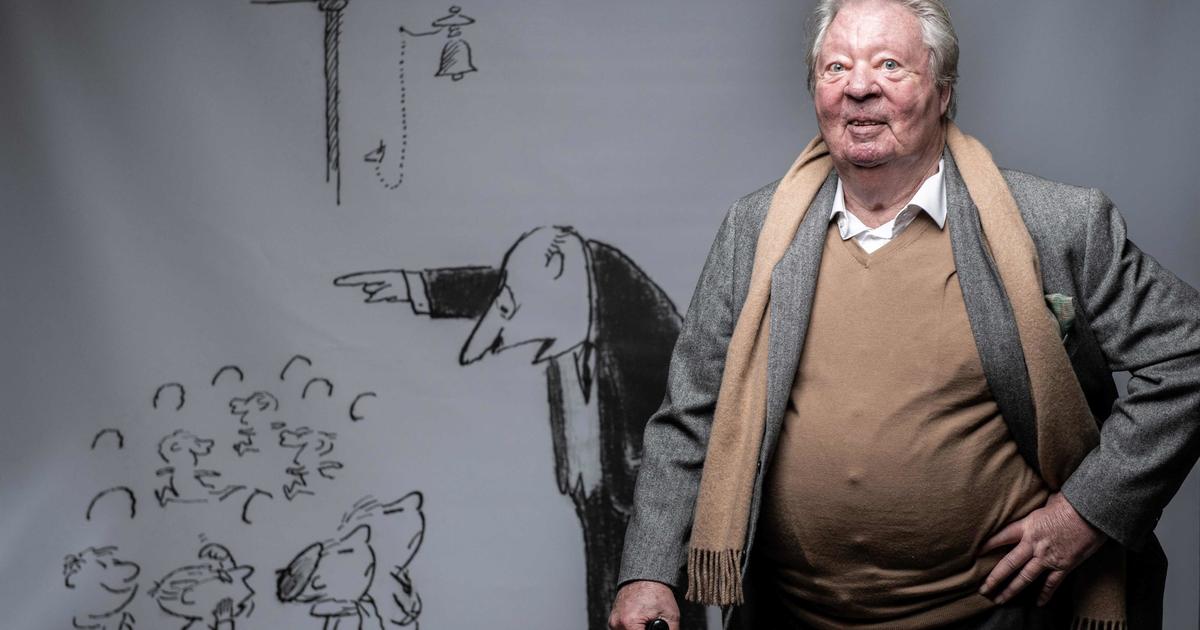

Sempé's countless drawings all have a family resemblance.

They evoke a universe that was entirely personal to him, and a world that has disappeared.

It's not the same thing.

They could have evoked a personal universe and at the same time a perfectly current world.

Sempé's world was a dream world, the antithesis of today's world.

Such is the meaning of the homage with which he is covered.

Through their unanimity, we perceive what has vanished.

There is no nostalgia, barely a regret, a somewhat sad observation, like a fatality.

Poetry of his drawings, they say.

The celebration is unreservedly justified.

His art exudes the finest, most sensitive poetry.

This is precisely what has deserted our world.

We are bathed in a pragmatism claimed as such, that of managers, triumphant finances, compulsive consumers, redoubled by the millennial anguish of an environmental disaster, to which is added, emerging from the most archaic humanity, the threat of nuclear devastation.

Read alsoJean-Jacques Sempé, the moralist

In Sempé's drawings, we do not encounter the implacable harshness of commercial constraints, nor the horror of war, nor the present beyond which we can only discern viruses, burning forests, melting glaciers, migrating peoples, religious fanaticism, racial hatred, the return of the worst, the enigma of a future that doubts its survival.

Sempé's drawings evoke a world which is being born, which is reinventing itself.

Even the late drawings, those of his last years, retain the innocence of those who made him famous.

His personal universe is of course related to childhood.

The reasons which explain it belong to him, as to any poet.

Jean-Michel Delacomptée

His personal universe is of course related to childhood.

The reasons which explain it belong to him, as to any poet.

A matter of temperament shared with similar.

It is no coincidence that, as he confided in an interview, he loved the cartoonists Bosc and Chaval, Robert Doisneau, Charles Trenet, if he had Jacques Tati for a friend.

They had the same taste for tender fantasy.

Or if he said: "

It happened to me to become, at times, reasonable but never an adult

", a sentence illustrated by the adventures he tells us, in the company of Goscinny, in Le petit Nicolas.

The school he describes has nothing to do with the formatting machine now dominated by pedagogical experts and ideologues.

We discover neither the theory of the genre, nor the stereotypes to be banished.

The kids play football, have schoolbags, teachers who scold them, do homework, heckle nicely.

A framed but joyful freedom.

Anne Goscinny: "

Little Nicolas is a kind of universal child

".

Nothing symbolizes it better than the way you run.

An adult who runs is that he is in a hurry.

Children run aimlessly, to exert themselves, for fun.

The children of Sempé run a lot.

We don't know to what.

They simply run, for the joy of living.

They exist without asking for anything more, in which they are innocent and pure, hence their incredible charm.

A charm whose marks they retain once they become adults if they know how to remain children, as Sempé himself says so.

His poetry floats in the air of a bygone era.

It was that of the France of that time, to a large extent that of the post-war period, which, in Sempé's drawings, was continued by a fidelity to oneself - to the childhood that he carried in him as at the time when it had fructified, and whose resigned nostalgia nourishes today the homages to the poet that he was.

Jean-Michel Delacomptée

Alongside his personal universe, his drawings express the world around him.

At least, a certain truth of this world which also accounts for others than him, for example Jean-Michel Folon, Raymond Devos, Hergé or Prévert.

The poetry of these observers echoes his own, it floats in the air of a time now gone.

It was that of the France of that time, to a large extent that of the post-war period, which, in Sempé's drawings, continued with a fidelity to oneself - to the childhood that he carried in him as at the time when it had fructified, and whose resigned nostalgia feeds today the homages to the poet that he was.

It is the representation and then the imprint of this France that the press, including the

New Yorker

, has constantly sought by publishing this instantly recognizable stroke of the pen.

Testimonials, almost proofs, as these evocations agree with the truth of things.

He captures the daily life of real life through snapshots that he doesn't feel the need to caption.

They leave you to think, and that is enough.

Poetry proceeds from it, she who loves silence.

Jean-Michel Delacomptée

In the times of yesteryear drawn by Sempé, there was optimism mixed with astonishment.

This made it possible to dream without being fooled.

Sempé abstains from caricature because he abstains from judging.

He observes without condemning, or if he condemns, it is out of sight, and above all in silence.

He captures the daily life of real life through snapshots that he doesn't feel the need to caption.

They leave you to think, and that is enough.

Poetry proceeds from it, she who loves silence.

These are flowers that grow in sidewalks.

To translate into words what his drawings evoke would be to betray them.

Black and white, movements just suggested, moments stolen by the hand that traces, like a long thought-out pencil photo.

He worked like this, in the depth of the surfaces.

Allow me, to say a word about the man, an anecdote that no one knows.

In 1980, in Paris, a young Slovak screenwriter named Natalia, who had just lost her student grant following her request for political asylum, met Sempé.

He immediately offered to help her by asking her what she knew how to do.

Write scenarios in French, she could not yet.

She told him that she spoke several Slavic languages, and that she would be happy to work in a publishing house as a reader of manuscripts in Slavic languages.

He addressed it, at Gallimard, to Yannick Guillou, who directed the section of Slavic languages.

He immediately gave him work.

Learning of Sempé's death, Natalia told me this story in a letter which she concludes as follows:

“Sempé was good, generous, benevolent.

He told me one day that he couldn't see a homeless man without tears coming to his eyes.

True goodness, like genius, is not so common.