In the 1989 film "Follow Him" (or "Dead Poets Society", as it is called in English) Robin Williams plays an English teacher who changes the lives of students at a conservative boys' school through alternative teaching methods for the subjects of poetry and literature.

Williams presents his students with a new approach to familiar topics, thereby changing and reshaping their worldview.

The movie "Field of Dreams", which was released in the same year, is defined as a sports drama that unfolds in the life of a character played by Kevin Costner, who hears an inexplicable voice calling her to build a baseball field.

"If you build it," whispers the mysterious voice, "he will come."

True, these are films in apparently different categories, and they undoubtedly point to a trend in American cinema of the late 80's and early 90's.

But at the center of them is a similar idea: a mental breakthrough and a change in the way we perceive a certain art are only a matter of vision and realization.

The four stories before you could easily have inspired an award-winning Hollywood feature.

At the center of each one is an idea, a change that materializes as we approach to implement it.

The four numbers promoted, took part in or initiated some of the most important groundbreaking educational institutions in Israeli culture.

With the help of inspiration from other places, an original idea or an almost accidental unfolding of events - they all started from a kernel of an idea.

Then came Miri Mesika

At the end of the 1970s Yehuda Ader was already a well-known name in the music industry, not least thanks to the band Tamuz in which he was a member alongside Shalom Hanoch, Ariel Zilber, Eitan Gedron and Meir Israel.

After the band broke up in the middle of the decade, Adar - then without the band (at least temporarily) went to Berklee College of Music in Boston.

There he was exposed to a culture of musical education that he had never known before.

The graduates produce their first EP already at school.

Ader (on the right) signs a joint venture with Berkeley College, '93,

"After Tammuz I went to Berkeley in 1977 and I didn't know why I was going," he says.

"I spent three amazing years there, where I was exposed to classical music and special arrangements and compositions, and I realized that learning music in the way that you learn there really develops your work and creates a connection with other people. I returned to Israel, joined the band 'Duda' with Danny Sanderson and Gidi Gov, produced the album 'Kelf ' of David Baroza, and while working I decided to realize an idea that I had had in my head for years, ever since I lived on the kibbutz. I saw the Berklee model and said, 'Let's do it in Israel.' Agmon, Amikam Kimelman, Orli Sela and Heri Lifshitz. We were the daring seven, in fact."

After impressing the mayor of Ramat Hasharon at the time, Moshe Verbin, the group founded in 1985 what would become "Ramon" - a music school that was the first of its kind in Israel in terms of teaching methods.

If until then music studies in Israel were a field that included mainly theory, Ader and the gang wanted to create a place that would allow musicians to learn, develop and grow in an organic way, all this while connecting with other musicians.

One that gave birth to well-known Israeli bands - from Aviv Gefen and Ayot to "All the studs in my house".

"I remember being with Chava Alberstein in the studio. We were in the middle of recording her album 'Mahramir', when I said I had to go because I was very busy. She told me 'school is more important.' And really, on October 29 of that year we opened the first day for studies with 60 students.

"They kept asking 'why do we need you?'" he recalled.

"We said - we need a place that allows people to write their songs, to improvise, but mainly to create themselves. We opened the first year with very talented people: Etti Ankri was in the first cohort, Eran Zur, Shmulik Neufeld, the Tatoo band, they really stood out at school. In general, we always said that the first cohort was full of people who just went for something that was terribly important to them. The school was full of creation, both in terms of core courses that should be taught and also jazz, creation, songwriting. I invented a course that is defined as mythological today, because I teach It's been the same for 37 years, 'composing songs A' it's called."

Aviv Gefen's first album was also written in Ramon, he says.

"We set up a place where you put a pool of excellent musicians, and you just have to fish for the fish that suit you. The classical academies gave their own answer, but my vision was to create a center of creation. For me, I set out to help other people become amazing musicians and give a chance to a person who comes from every hole in Israel to come and fulfill oneself. Many of our people did not grow up in Tel Aviv. They came from the periphery and from all kinds of places and found themselves and the partners for their creative lives in Pomegranate."

What was the biggest challenge you faced? It took time for people to understand what change you are bringing.

"There were and still are financial challenges. We are much less supported than all the acting or film schools, even though we are much larger. We are constantly in a war of existence. We would like to be supported by the cultural institutions in Israel, just as there is support for cinema, theater, and dance. The second to the establishment of Ramon, I had no money for salaries. I gathered the teachers, I said, 'Guys, I'm staying, you are welcome to leave'. But no one left."

In those years you were already a well-known musician and producer. Why did you need a school on your head?

"You are so right. I was successful in the things I did in music as a guitarist and producer, but the part of connecting to the community and doing something that is bigger than me is at the heart of my personality. And really, I don't stop with it. I am constantly searching and inventing and investing in this thing."

Real life as a musician.

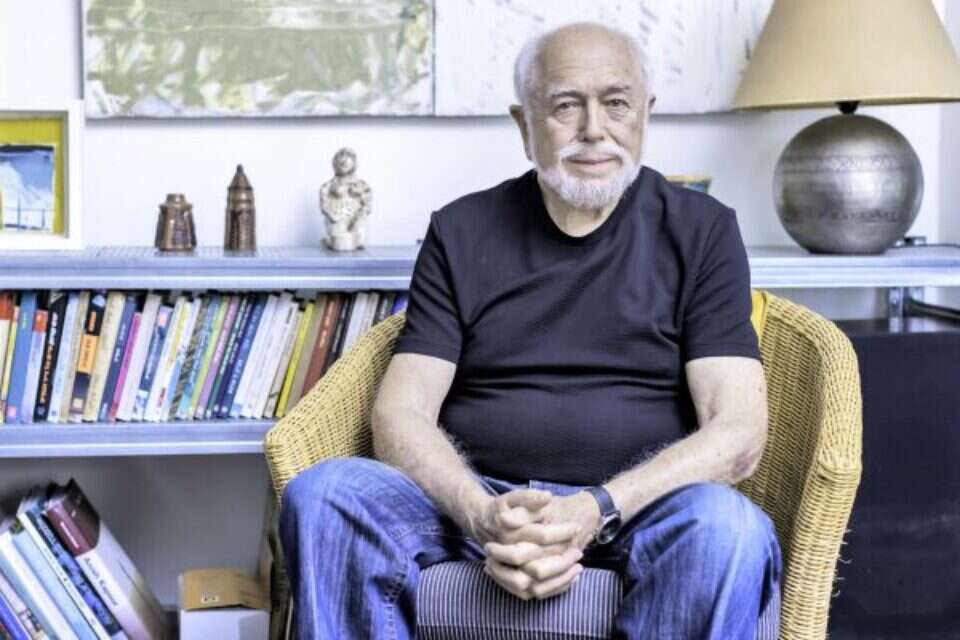

Yehuda Ader, photo: Efrat Eshel

When did you realize you were able to change something in the industry?

"I think it was in 2005, when the group of Miri Mesika, Keren Pels, Aya Korem and Eric Berman broke out. Suddenly there was a crazy enrollment here, Aya Zahavi Feiglin and Hila Rukh arrived here. The school not only grew a lot then, but also received talented people is very".

Since then, "Rimon" has become a thing in Israeli musical culture, not least thanks to an approach that prepares those who study it for real life as a musician.

It enables a joint degree with Berklee, and along with musical knowledge, its graduates learn about a variety of aspects in the music industry - from public relations and dealing with the media to the possibility of pursuing a degree in teaching.

In recent years, the graduates produce their first EP (short album) already at the school (singer Yasmin Moalem is a good example of this), and work with communities with special needs.

Recently, the school also joined the worlds of advanced technology, with an agreement with the "Art List" company that allows graduates to work, develop and earn in high-tech as well.

"In retrospect, I understand today that what I founded is a startup," says Adar, "they just didn't call it that back then."

Photo film in the bath

In 1978, if the amateur photographers of the city of Tel Aviv were interested in developing their photos, they were faced with the possibility of paying for a "darkroom for rent".

No one knew then that the small basement apartment on Shlomo Hamelech Street, which offered a practical solution for photography enthusiasts in Zion, would in a short time become a place to acquire theoretical knowledge, and would later develop into an educational institution with a reputation in Israel and the world, which would also change the perception of photography in Israel.

The room, which will move to Bialik Street in the city and become a college, then to a building on Allenby Street (and then again, to Rival Street) was then opened by Aryeh Hamer and Michal Rovner - a young and modest couple, who had no intention of creating a revolution.

"Arie started as an amateur photographer and he was very good at it," says Rubner, who is today considered one of the most successful Israeli artists in the world, who works in the fields of photography, video and installation.

"He had an idea to open a darkroom, instead of people opening film in their bathtub. That's what 'Camera Obscura' means. People could come, pay by the hour and enjoy such a darkroom. I, who was his girlfriend at the time, said I would be happy to be a partner in this venture. We An ad that said 'instead of in the bathroom - do it with us'. It was humorous."

Magazines published under "Camera Communications" publishing house,

Soon, by force of inexplicable inertia and without any premeditation, the place became a pilgrimage center for those who wanted to learn the secrets of the field.

"There was no vision in advance to establish a school that would reach where it will, with hundreds of students a year and with credit agreements with institutions from around the world," she explains.

"It came about the way a real creative process comes about, some good intuition and dedication to an idea. We didn't think of it as a business. Aryeh didn't come there with a commercial agenda. The photo studio and the photography itself were something he loved to do, and he was also very generous. He wanted To share a hobby, which technically can be challenging at times, with other people."

Over time, what would later become the camera obscura art school also became a place that inspired her to document and photograph.

"I wasn't a photographer at that time," says Rovner.

"I studied philosophy, cinema and television at Tel Aviv University. People came to develop pictures and then asked Aryeh, who was there the whole time, if he could explain to them how to develop, etc. In a short time Aryeh organized several lecturers to come and explain how to print, and the whole thing very quickly This began to expand beyond photography and printing in the technical sense, and also included looking at photography as a kind of creative language, a very significant language of expression. A year or two after that, the first cycle of photography opened at the Bezalel Academy of Art and Design. I studied in this cycle and some of my teachers at Bezalel taught at our camera Obscura. There was no support, there were no donors, no people we asked for money from. There wasn't this thought of 'how are we going to manage.'

And the most accurate definition I can give it is 'melting pot'.

was a great creative vector.

A very big event, which everyone was drawn to."

No commercial agenda.

Michal Rovner, photo: Sion Farage

It's the 1980s in Israel, and the discourse around photography (just as it will later be around video) has not yet significantly established that it is an art form at all.

At this time the Camera Obscura College becomes a meeting place for beginning photographers before and after the class, and a center for the exchange of creative ideas where the field will begin to receive artistic recognition and appreciation.

"Bezalel was a very different school in this respect, I think more rigid," she says.

"A bit like film and television studies, where you have to say first what will be in the film, and there were endless work reviews.

"I remember at Camera Obscura, people would stay for hours after school, talking, exchanging ideas, getting inspired. Since I was with Aryeh at the time, this was really our life at that time. They didn't think of opening a place where you could learn artistic photography before. I don't remember that there was That kind of thing. Other places taught very technical things - industrial photography, journalistic photography. Camera was the connection of that to art. People could learn the technique needed for artistic expression, like institutions like the School of Visual Arts and the Pratt Institute. In that sense it was a pioneering school ".

The modest venture that began on Shlomo Hamelech Street, brought Rubner to an extensive and impressive international career.

"After Bezalel, I didn't touch the camera for more than two years because I had to erase the didactic voice. And one day something woke me up to take pictures, and that's how I started taking pictures again. Shortly after that I left for New York, and from there I already chose art. When I left, I remember that there were about -300 students per year.

The technique needed for artistic expression.

A joint project of the "Ha'ir" newspaper with a camera obscura edited by Adam Baruch, late 1990s,

"It was a special thing that I don't think was like it in Israel. Especially in the really strong energy that was there. We were young and beautiful, but not only young and not only beautiful. I always say 'ana panna janana' - I'm a crazy artist. That's how Arya was, And I owe him a debt of gratitude for the fact that thanks to him and the camera obscura I got into photography. It was his vision, and I will always give him credit for the fact that thanks to him I entered the field of photography and art."

The politics of the theater

"My first year as a teacher at the kibbutz seminary was around 1973, right after the Yom Kippur war. I taught there the aesthetics of drama, acting and theater," recalls Yehoshua Sobol of his early years in the theater department of the old institution.

Although the Kibbutzim Seminary was established as early as 1939 as a teacher training institution (or the "Teacher and Kindergarten Training Plant", as it was called then), but since the 1970s it has also housed the Faculty of Arts, which has become a central and important institution in Israel for studying art, dance, design, Communication, cinema, and of course theater.

Like other institutions in this article, here too the strength and pioneering spirit of the young group was in the new, less rigid and rigid approach, which it took when it comes to imparting practical knowledge in the art of acting.

"The teaching framework was very free and very creative, that's what characterized the department. The creativity," he says, "what's more, at a certain point they merged the teaching teams with graduates who came from the creative drama department, which was a different department intended for teachers. People who worked in creative drama came from there About certain techniques of making theatrical works accessible to a wide audience, an audience of students. I remember that one of the department's students, Amira Kaminer, who studied there and then moved on to teach in the drama department, really excelled at this. She brought with her techniques she developed during her studies in the course.

Sobol's play from '88 created a big media storm, which reached the Knesset.

"Jerusalem Syndrome" 2010 version performed by the students of the Kibbutzim Seminary, photo: Eyal Landsman

"This merger between the creative drama teachers and the drama teachers created a class where the work was experimental and very free. I think this spirit was passed on to the graduates of the theater class at the seminary, from which many movement, drama teachers, directors, choreographers, and of course actors came out."

The change in attitudes, he says, was significant.

"Actually, as soon as you were chosen to be a teacher in the department and a subject was assigned to you, you were given a very large degree of freedom to decide and choose how you teach and what you teach there. And it is not a forced framework, but a very free one. This was the atmosphere in the department. This was instilled by the heads of the department during That I worked there, which were Yishai Dan, Assaf Or, Shmuel Shila. These were the directors of the department, and they brought with them the approach that the teacher studies theater and brings his students to creativity. That was the name of the game, more than anything else.

"The study framework in the drama department seminar was very free and each of the teachers in this framework could bring the type of theater he believed in and that interested him," he explains.

"This is in contrast to some dry academic approach that says you have to study this way and that and here you have Torah - if not from Sinai, then at least from New York or Moscow."

One of the approaches he developed inspired him to write the memorable and controversial plays he wrote.

"I would sit the actors in a circle," Sobol describes an exercise he devised in the circle, "someone who had some kind of association with a place for which he was expressing, say, a prominent phenomenon in society, would get up, enter the middle of the circle and mime the place. Anyone who understood what place it was about joined in and enriched the the expression of this place, and so on. Let's say a tramp, which evokes a memory of an army, which evokes a memory of a range. We would work on it for two hours, at the end of which we had a group of say 15 male and female students and a variety of places that play a role in the Israeli collective consciousness. This exercise was later used me when I wrote the play 'Jerusalem Syndrome'. I actually based the play's structure on this exercise, an exercise of transformations. That is, changing the identity of a place and the time of occurrence. This is how a play was created that threw the actors and spectators from the days of the Second Temple to the present day, into a hallucination of the future, to some Walking back to the time of the Holocaust,

And so on.

In the play, I tried to bring the collective consciousness associated with the association of destruction, the destruction of the Second Temple and the Jerusalem syndrome."

The play written by Sobol created a big media storm, which led to a special discussion in the Knesset.

When it premiered in January 1988, outside the Bhima Theater in Tel Aviv there was a large right-wing demonstration against its continued performance.

Members of the so movement even increased the purchase of tickets for the show and disrupted the series, which was interrupted no less than six times.

Later, the storm led to the resignation of the playwright from the management of the Haifa Theater.

Another play written inspired by his days as a seminary teacher was "Joker".

"I served six months in the reserves during the Yom Kippur War, and this period affected me. 'Joker' dealt with a group of reservists whose social reality in the environment they came from greatly affected the atmosphere of the unit in which they served. Later it influenced a television play called 'Hafif' ', a television drama in which Ze'ev Roach and actors from the stage, Yitzhak Hezekiah, and others acted. It dealt with a reservist who returns to civilian life and discovers that his place has been taken there, in every respect. Six months of reserve service did not stand to his credit when he returned to civilian life, but he had to struggle anew For occupying his place in the workplace and in society in all kinds of fields."

A collective consciousness associated with the association of destruction.

Sobol (right) in rehearsals for his play,

Sobol's years at the seminary, which were spread over different periods (he retired from it in 1987, but returned in the 1990s and taught there until about a decade ago) helped shape his own career as a theater person with an important political voice in his generation.

"I think the contribution of the seminar is in engaging in social theater, in significant issues such as the situation of different strata in society, underprivileged strata," he says, "theater with political undertones."

exposure to the South

Just before the turn of the new millennium, filmmaker Abner Feinglerant found himself looking for work.

He started to set up his independent studio in Kibbutz Boror Ha'il in the northern Negev in front of a pool, among peacocks and Thai workers, intending to become what he defines as a sort of troubadour documentarian.

He took a camera, got into an old car, drove to places in Israel that interested him and documented them.

He later edited the materials himself.

Cinematic nomadism in a southern country, if you will.

But at this point he was already a family man with a wife and children, and had to find a quick and convenient source of income.

"Then I decided to do the thing I hate the most," he says, "and I went to teaching."

Unheard voices.

Abner Feinglerant,

"In general, I intended to make a living from about NIS 4,000 a month as a teacher and continue to wander the country, making films in a very personal way," he tells of the way he began teaching at the Negev College.

"There was a school for engineers and a program for production, a certificate program. Something very beautiful, a kind of collective home video but with aspirations to touch art. Something rudimentary but very touching and beautiful. And they started to build infrastructures of communication, cinema, in this area. At this stage I was teaching there About a year and a half ago, and there was a media department opened by Prof. Haim Berashit. He opened the department, brought in good people, and then asked me: 'Come and concentrate the field of production and creation.' I told him, 'Who needs that? Let's start a real cinema department! Academically Let's compete with Tel Aviv University. We will be better than them.'

"Haim said to me: 'Great, write a show'. Now, who am I? I barely have a BA, I've made one film, I'm still working on my film 'Ava' on my way, of a stuttering car, a camera, a backpack on my back and living on people that I meet along the way. It is a personal, investigative method. Such a traveling anthropologist. But I agree to his proposal. I said - I will write everything I would like to learn, in the way I want to learn, in contrast to the study method I saw at Tel Aviv University. I took curricula from Columbia University And New York and somewhere in Australia and I wrote a new curriculum together with Prof. Berashit, which focuses on documentary anthropological cinema."

Almost without meaning to, Fainglerant found himself one of the founders of the School of Sound and Screen Art at the Sapir Academic College in Sderot, an institution he would head for almost two decades, not before establishing the South Film Festival.

"For 18 years I'm not sure I slept," he says, "I founded a film school that started with 20 students and finished with 450."

Not an obvious thing, considering the fact that this is a war zone.

For Feinglerant, born in the south, his flowering is nothing less than a mission.

They will understand the enormous potential that exists in the place I am talking about.

They will understand'".

A state of mind of obsession and very deep belief.

Feinglarnet with his students,

Over the years, the school also plays an important role in changing the content world of Israeli television and cinema.

"In 2002, there is no periphery in cinema and television. It's all Tel Aviv stories, as if Tel Aviv wants to be New York," says Feinglerant.

"I said - we have the greatest cultural advantage! Because everyone who lives here in the south comes from the third world in general. My ethos was to bring to the front of the stage the voices that had not been heard until then in Israeli cinema. At that time, the beginning of the 2000s, the cinema that fascinated me the most was cinema My world. So I wrote a curriculum that connects immigrants and cinema. I started from the premise that we are the truly rich, because we have a cultural source that is not found elsewhere and in Israel they do not understand its power and strength. I think that as a result of this, Eastern cinema and the social periphery have become a bon ton in Israeli cinema. In 2001 I wrote all these things, like some kind of prophetic thing like that. I think we showed that in the periphery you can establish the cultural enterprises,

In a somewhat ironic way, Avner brought his vision of the blossoming of the wilderness to the big city.

Recently, after leaving Sapir and going on sabbatical, Avner moved to the kibbutzim seminary and established the faculty of dance, film and television arts - right inside Tel Aviv, on Ahad Ha'am Street, not far from Migdal Shalom.

"With great regret," he describes the move to the center.

"Perhaps it should be done in Tel Aviv so that the south understands that this is the right model."

were we wrong

We will fix it!

If you found an error in the article, we would appreciate it if you shared it with us

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/GP2ZXWJRROQQUNBAGJPH3WIOVQ.jpg)