The following story, which touches on one of the fundamental controversies of religious Zionist politics, belongs to the branch of history, but it is not yet a miracle: the year is 2004. These are the days of disengagement, the eve of the expulsion from Gush Katif. The members of the Knesset and the ministers of the Hempdal have been sitting for hours with those who are defined as their spiritual leaders, the chief rabbis at the time Rabbi Avraham Shapira and Rishon Lezion Rabbi Mordechai Eliyahu, and are trying in vain to understand from them whether to withdraw from the Sharon government or stay in it. , the two rabbis remain silent and stubbornly refrain from instructing members of the Knesset on Halacha.

Until all of a sudden Rabbi Shapira shakes off his seat and slams the five members of the faction: "What do you need us for anyway?", the MKs are amazed. Orlev replies: "You called us in order to impose a teaching on us.

The rabbi demanded that we come." Shapira answers: "I didn't call you.

I'm not the rabbi of the Hempdal... just someone who has a personal question, to come and ask me."

With them: "Rabbi Druckman, is it true that they called us here? You are our rabbis."

But Shapira answered: "I am not your rabbi."

This confusing situation ended with Rabbi Eliyahu Laitham and Yitzchak Levy's personal decision to resign from the government, but the embarrassment that remained in Rabbi Shapira's room full of books was carried by the MLAs for many more days.

This lesser-known historical event is still relevant today to anyone who wants to crack the codes that drive religious Zionist politics in recent decades.

The MPDL is no longer with us. Druckman, who in a sense inherited the greats of the old generation, became an address for religious politicians who make pilgrimages to him. After a while, Efi Etam tried, without much success, to integrate into Likud. Over the years, Likud itself has become a home for many of the people of the knitted caps. The number of religious MKs in it throughout many Knessets equaled the number of religious MKs in the sector party, and sometimes even exceeded it.

However, beyond the changes in roles, time, place and characters, this entertaining story illustrates more than any other two profound processes that the religious-nationalist public has gone through since those days.

If 18 years ago the issue of the Land of Israel and its territorial integrity stood as an exclusive matter at the center of the existence of the religious-nationalist public, then since then broad parts of the religious-Zionist society also pay a lot of attention to the other two sides of the well-known triangle: the people of Israel and the teachings of Israel.

No longer just the Land of Israel.

Beyond that, the debate about the place of the rabbis in political-policy decisions (Bennett claimed at the time that he abandoned the "Jewish Home" precisely because of this background) accompanies religious Zionism to this day and is symptomatic of similar discussions on a series of other Torah and value issues.

Sometimes it is about the legal system, sometimes about conversions and other times about issues such as the status of women, sexual abuse or kosher.

This discourse, on a variety of these topics, embodies the wide range of consciousness among a public that currently numbers about 600 thousand with the right to vote (about 15 mandates) - between orthodox and modern orthodox; between conservatism and innovation, and between liberal and religious religious and A pious and religious public many times more.

4 manager.

2 from Hebron

This diversity is not lost on the Knesset either: in the last two decades, many religious MKs have joined parties outside the sector party and in fact inherited, certainly numerically, the place of the elite of the kibbutzim and moshavim in the first Knessets. At the height of the parliamentary power of the moshavim and kibbutzim, pairs, triplets served as MKs , and sometimes even quartets, who came from one place of residence.

The settlement that sent the largest number of representatives to the Knesset was praised, but kibbutzim such as Ein Harod (Yitzhak Tabenkin and Aharon Cizling) and Mishmar Ha'emek (Yaakov Hazan and Mordechai Bentov) were not far behind.

Jubilee years later, when another population segment - the knitters and the settlers - reached the peak of its parliamentary representation, small settlements again sent pairs of MKs to the legislature. Thus, for example, Nissan Salomiansky and Shaul Yahlum from the MDF (Elkana), Uri Ariel and Dr. Aryeh Eldad from the National Union (Kfar Adumim), and today - Orit Strock and Itamar Ben Gabir (religious Zionism) from Hebron-Kiryat Arba.

Almost a quarter of the members of the first and second Knessets, 28 MKs, were members of the working settlement, the vast majority of them members of kibbutzim. Since then, their number has decreased. In the outgoing Knesset, only four kibbutznik MKs served.

At the same time, the number of "knitters" grew, many of them residents of Yesha. In the 16th Knesset, 11 settlers already served as MKs, and more religious people who were not residents of Judea and Samaria.

In the outgoing Knesset, as in the 19th Knesset, 20 religious MKs served (except the ultra-Orthodox); not bad for a sector whose direct electorate stands at only 13-15 mandates.

And yet there is a significant difference: the MKs from the kibbutzim and the moshavim served in the parent party or their sector. The knitted MKs crossed camps and were scattered over the years between the Likud, Blue and White, Yesh Atid, Kulanu, Yisrael Beitenu and a host of other parties.

Why did this happen?

It seems that in the story of religious Zionism, its electors and its voters, there has been a built-in paradox for years: the greater its success in emerging in Israeli society, integrating itself into the central decision-making junctures of the state and realizing its ideology for the sake of Klal Yisrael - the less its political power.

From a peak of 12 mandates in the 1977 elections, the sectoral party deteriorated over the years to a single-digit number of mandates - sometimes 3, sometimes 6 (and there were also an exception or two).

As much as it deepened the anti-sectarianism education among its graduates and further entrenched the decree of joint responsibility for "all of Israel" - the more religious Zionism single-handedly diminished its political power.

Her political failure was her success, and vice versa: her success was her political failure.

In the elections to the 21st Knesset, less than four years ago, the two parties competing for the united vote stopped mentioning religious Zionism.

The new right and the union of right-wing parties have officially highlighted that the right-wing and non-religious dimension has become dominant for them.

Things came to a head about two years ago with the disintegration of the Jewish Home, the successor of the historic mother party, the Jewish People's Party, after 120 years of political existence.

The political collapse of religious Zionism stood in stark contrast to its public success.

In recent decades, religious Zionism has occupied the IDF's chain of command. It has "raised" the head of the Shin Bet, deputy chief of staff, generals, police commissioner, prime minister, vice president of the Supreme Court, university presidents, doctors and leading researchers.

She proudly presented knitted caps that became an integral part of the leadership elite in many fields, but at the same time continued to run politically in a sectional party.

For the general public, the contradiction was too sharp.

He had difficulty being non-sectarian in all areas, and remaining sectarian only in the political field.

The place of the mezuzah

MK Orit Struck from the religious Zionist movement interprets things differently and takes reservations from this thesis. Struck believes that "in order to represent religious Zionism it is not enough to wear a kippah or a skirt, and to observe Shabbat, kosher and the purity of the family.

The broad definition of religious Zionism is one that sees the State of Israel as 'the beginning of the growth of our salvation', and in contributing to the state - assisting God in the act of redemption. This is what is called 'working with God'. This is what usually distinguishes religious MKs in other parties from "Kim from the 'Sector Party', that this belief and worldview is a very central thing in their lives that guides them practically and not as a marginal thing."

How are you and your friends different from Likudniks like Yuli Edelstein, Amit Halevi, or Shlomo Karai, or Malkin in a new tikvah?

"When it comes to the Land of Israel and its destiny - they can have the same influence as us. When it concerns issues of religion and state - they cannot. Their parties limit them. For this, a separate party is needed."

The Masker Institute, which specialized in surveys on religious Zionism, previously estimated the "Torah group in religious Zionism" at 33%, the liberal group at 26% and the classical religious Zionism between them at 41%.

Your party presents itself as a home for everyone, but there is a dissonance between this presentation and the fact that until now you have been an orthodox party.

"This is exactly the reason for the large census we conducted. We realized that all shades need a political home. We passed the decision to the general public. Everyone had the opportunity to function and vote."

When a person like Miki Zohar fights for the Jewish tradition from within the great party of the national camp, doesn't that mean more than if the war is waged from the sectarian corner?

"This is why the Likud exists, which represents a very significant segment of our society, the traditionalists, a segment of the population of very high value and tribal importance. The Likud is the traditional party, but the religious-nationalist world is not traditional. It is not a world where the mezuzah has a place of honor in the home, but A world where the mezuzah is the center of the home."

You identify yourself with the settlement in Yesh, and as someone whose main concern is the Land of Israel, its integrity, security and development. What differentiates you from Yariv Levin?

"The public does not see the difference.

But the public saw Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon, two distinct people from the Land of Israel, uprooting settlements.

My number one insight and that of many is that if your commitment to Eretz Yisrael is not based on a deep faith and commitment to the Torah - it will not last.

I don't want to say, God forbid, that my friends in Likud are not loyal to the Land of Israel, but there is always a fear that if it doesn't come from the Torah side and God-fearing - something, in a certain situation, could go wrong."

The lack of electoral demand in recent congresses for the goods of a Zionist-religious sector party, Struck attributes to two fundamental problems: "One, our public is very integrated in its way of life, and this affects its voting patterns, and the second - the internal disputes, which do not start with the parties but with the rabbis and permeate Onward, deterrents."

Struck finds it difficult to forget that "Bennett and Shaked are the ones who destroyed the Jewish Home from the inside": "They changed the statutes beyond recognition and turned it into a party under the control of one man. It was once a very alive and vibrant party. They introduced into the Jewish Home norms of contempt for the holy places of Israel that were the basis The values that the party was built on. When the head of your party takes a picture with a hundred high school girls like some kind of rock star, and on the other hand people have trouble remembering one photo of him with a Torah book - this is not our spirit. As soon as they resigned, just before the elections, and went to form a government with the arm of The Islamic movement and smashed everything they promised the voters - they left behind a broken public."

We've split up enough

Former MK Amit Halevi, one of the founders of the College of Jewish Politics, number 36 on the Likud list for the 25th Knesset, sees things in a different light: "From the day I made up my mind, I didn't feel comfortable dividing myself into one sectoral party or another.

In the last hundred years we have moved from a reality of communities to a nation.

I have no interest in returning to the community model, and this is also true of the religious-national public, of which I am a member.

It's time to grow up.

When you are segmented once, you are then segmented into sub-sectors and endlessly into divisions.

This is also what happened to the sectoral political movement of religious Zionism.

I once saw an advertisement for apartments in Nof Zion: 'Live with people like you'.

Exactly the opposite: this is not true for us as a society, neither in settlement nor in politics."

"It is possible," Halevi says, "that in the first years of the state there was a place for a religious-nationalist party that would influence and shape the Jewish character of the state in legislation and budgets, but today, when things have become established, the broad public denominator that the Likud represents expresses what is really important - the Jewish identity of the state and maintaining About the Land of Israel. It is precisely the traditional public, which has no political parents, that needs a father and mother to take care of it, and that is what it finds in Likud."

Is a religious MK required or asked to help with sectoral needs? Is it even possible to do this from within the Likud?

"Certainly.

Me and my friends too.

When Ehud Barak as the Minister of Defense wanted to close the settlement meeting at Har Bracha and when it was on the agenda to harm the settlement meetings - Netanyahu and Miki Zohar and others (including me) prevented it.

See for example the war that people like Gadi Taub and Roni Sesover are waging today, outside of a sectional party, against progressive content and the tattooing of Jewish identity in the education system.

When I was the Chief of Staff of the Minister of Sports and Culture Miri Regev, we knew how to budget for voices that were excluded from the budgets and from the main stage for generations: community theaters, ultra-Orthodox creators and people from the periphery."

No head covering

Aliza Lavi, currently the chairman of the Film Council, served as a Member of Knesset on behalf of Yesh Atid in the 19th and 20th Knessets and chaired the committee for the advancement of women's status and gender equality. She dealt, among other things, with the fight against the phenomenon of sexual harassment in the public sphere and during her time the committee was at the forefront of legislative action to prevent the exclusion of women. Lavi, who, like Halevi, grew up in the cradle of religious Zionism, is a religious woman and began her political life in the MDF, as an assistant to the minister and former MK Shaul Yahlom. Lavi shelved her political ambitions to fight for a place on the MDF's list, after She realized, according to her, "from one of the most impressive women I've ever met in my life - Judit Hibner", that a woman without a headscarf has no chance of being a member of the Knesset there.

When I received an invitation from Meir Lapid to join Lish Atid, I understood that it was a center party of religious and secular people.

Together we built the chapter on religion and state in the party's platform, and I was a co-author of it."

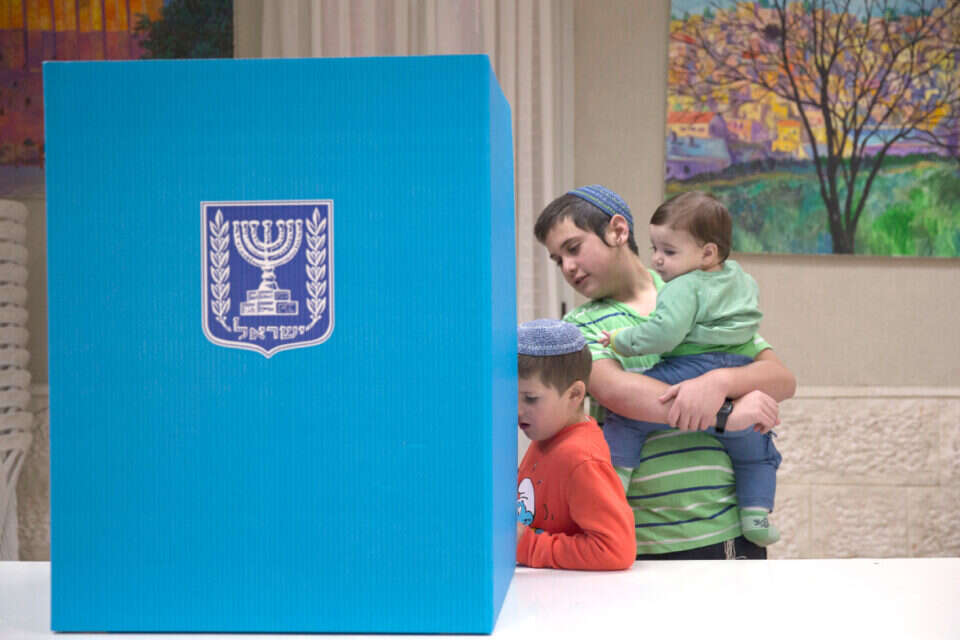

Naftali Bennett's victory celebration in the elections for the Jewish Home party, November 2012, photo: Yossi Zeliger

Lavi claims that Bennett and Shaked, as the leaders of the Jewish Home, did almost nothing in the fields of religion and state.

"Precisely, I and one of my friends in Beish Atid moved things. In the 20th Knesset there were five religious Zionist MKs, none of them from a religious party.

I, as a member of the Knesset, assisted the religious preparatory school in Machmesh, an ultra-Orthodox preparatory school. I was the one who addressed the rabbis of Europe on the issue of overseas moorings, and also when it was necessary to take care of mixing in the area of hotels in the Dead Sea, they contacted me and I harnessed the Shas people to the matter.

But Bennett allegedly opened the Jewish home, exactly in the direction of the non-sectors, which you are closer to.

"That's true, but along the way he changed his opinions and positions. When we needed him in matters of religion and state - he disappeared. The Likud, by the way, also pretty much refrained from dealing with these issues."

In your opinion, is there a need today for a Zionist-religious sector party?

"The way the sector party looks at the moment, of course not. The profile of Smotrich's party is homogeneous. You will not find in his party people like me, or like troopers from Blue and White, or like Rachel Azaria at the time from 'Kulana'. The difference between the different shades of what today is called Religious Zionism is so broad that it does not allow one central political house for everyone. This is also one of the reasons why many talented people from our public went to other parties."

The need for an imagined enemy

Prof. Yedidia Stern, who currently heads the Institute for the Policy of the Jewish People, further substantiates the view presented by Levi.

Stern, former vice president of the Israel Democracy Institute, points out that "unlike the ultra-Orthodox and the Arabs, who strive to differentiate themselves from Israeli society and maintain their religious and national identity apart from the rest, religious Zionism does not want to differentiate but to integrate," and therefore, in his view, "there is no need for a distinct Zionist-religious party." .

"In the past," he notes, "religious politics existed mainly to achieve two goals: religious legislation designed to realize a halachic vision for the Jewish state and to preserve Jewish identity in a religious sense, in the public sphere, and the second - allocating resources for the maintenance and development of various institutions of the sector - The education system, youth movements, yeshivas and more. The time of religious legislation," believes Stern, "has passed. Its flaws infinitely outweigh its advantages. From a religious point of view, not only is there no value in coercion, but it causes alienation from religion."

The religious branding, of dealing with the Jewish identity of the public sphere (Shabbat, marriage laws, conversion, etc.), in Stern's opinion, is a "proven recipe for failure", and regarding budgets - the religious, according to him, "are no different from any other group, and even in the absence of a dedicated religious party, The Knesset is saturated with religious Zionist MKs who realize the ambition of integration they were raised on, both in the coalition and in the opposition, so this concern also holds no water."

Hagit Moshe, chairman of the Jewish Home, once cherished the glory days of her party, which faded over the years. "My mother," said Moshe, "always says that only when the tree is lying on the floor do you realize how tall it was." Yair Ettinger, author of the book " Fromms" which deals with the disputes that divide religious Zionism (Kinneret Zamora Dvir Publishing House), has been documenting the many branches of the same metaphorical tree for years.

Ettinger, currently a commentator on religion and state affairs at KAN News, identifies the political breaking point at which the foundations of sectional politics were shaken, in Bennett's activity at the Jewish Home.

"The opening of his ranks, both at the level of content and at the level of personalities, and then his and Shaked's departure, greatly weakened the system and emptied the camp party of its content."

Prof. Asher Cohen believes that it began during Menachem Begin's time, when the religious-nationalist public found itself less threatened by the left camp of the labor movement, because Begin, the traditionalist, with his "good Jewish flavor" government, gave them the feeling that the Likud was also home.

"It is possible that the seeds were already germinated then. It is possible that a political force, including religious Zionism, needs an imagined or real enemy to mobilize the camp. It is possible that once the religious nationalists, at least some of them, were freed from the sense of threat and felt sufficiently in Likud at home, the power of the sectoral party weakened. This comfortable feeling , devoid of the threat, became even more powerful during Netanyahu's time, many of his advisers and people came from the knit sector. For many, it became almost emotional. Netanyahu managed to bring many religious-nationalists to identify with a party that is not the party of their sector in a way that even Begin did not do."

And this alone explains the fact that the knits were spread everywhere and scattered among all the parties?

"No. Something else happened in religious-nationalist politics, whose public grew greatly and became very diverse, especially from a religious point of view. For many, many years this public wavered around one and only one issue - the Land of Israel. This story created the tension between those who are willing to go as far as A confrontation with the state and with the left, and with those who had more clear boundaries in this matter. Today, the disputes have changed - more about the Torah of Israel and the people of Israel. This concerns the issue of girls serving in the army, the issue of the Jewish family, what kind of religious-nationalist are you? Hared." Li or Lite?

Conservative or liberal?

Bennett did an experiment.

His ethos was to be a partner of the secular.

He tried to reproduce in politics what he experienced in the army;

The joint ambush in which the religious part of the settlement, the leftist and urban kibbutzniks from Ramat Gan are taken.

In politics, unlike the army, it lasted a year and fell apart."

Ettinger also comes from the sector.

"There is a public that still needs a sectoral party," he estimates.

"Part of him is known to me from the wide circles of my family. These are people who have voted for FDL all these years and the last decade shook their political world.

In this fifth election they find themselves very confused.

The religious-national ideology was privatized.

Today, the national religious are everywhere, even in the political field.

It is very difficult today to sit in a laboratory, as in the past, and say: This is the religious-nationalist party I want.

The diversity is huge, the sector has grown a lot and its ends are far from each other."

were we wrong

We will fix it!

If you found an error in the article, we would appreciate it if you shared it with us