Supporters of Rejection in Santiago, Chile, on September 4. MARTIN BERNETTI (AFP)

The overwhelming victory of Rejection in the constitutional plebiscite on September 4 has left President Gabriel Boric, and the groups in favor of the new text, in a position that forces them to seek dialogue and moderation.

That's what the left did, in fact, in the 1990s.

The geographer Jared Diamond has a short but very valuable analysis of the conciliation process that took place in Chile after the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973-1990).

He reflected on it in his book

Crisis: How Countries React at Decisive Moments

(2019).

According to Diamond, the left at that time had to abandon the intransigence of the past and learn to tolerate and negotiate in order to reach agreements with other political forces, and thus be able to begin to heal the historical wounds and begin the reconstruction of the country.

This is how the Concertación originated, the coalition that governed the country until 2010. What happened during that period of Chile's history can serve as a reference for the new constituent process to be successful.

The conciliatory rhetoric and the latest changes in Boric's cabinet are indicators that the Chilean president has understood his situation.

It is not clear if the same can be said of the other sectors that promoted the change.

More information

The five keys that explain the Chileans' rejection of the new Constitution

The conventional ones —representatives democratically elected to write the new Constitution that was voted in a referendum— aspired to elaborate an environmentalist, feminist and indigenist text, which would serve as a basis to deal with the enormous inequality of the South American country.

They were empowered to know that 78% of citizens had been inclined to convene a Constituent Convention in 2020. The result of that year "intoxicated" the left, according to Diana Aurenque, director of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Santiago. From Chile.

The left-wing groups thought that the majority of the people agreed with their positions, but finally only 38% of the population voted for Approval.

Aurenque and other experts agree that the result of the plebiscite cannot be attributed solely to one cause.

The low approval of the Boric Government (in August it was around 37%) and the inappropriate behavior of some conventional definitely affected the result.

But the content of the text, as such, was one of the most determining catalysts.

It included controversial points such as the declaration of a “plurinational state” and the establishment of “indigenous courts”, which fueled fears that it would end in a country with two judicial systems.

The recognition of the right to housing also generated much discussion, which, according to the opposition, opened the door to expropriations.

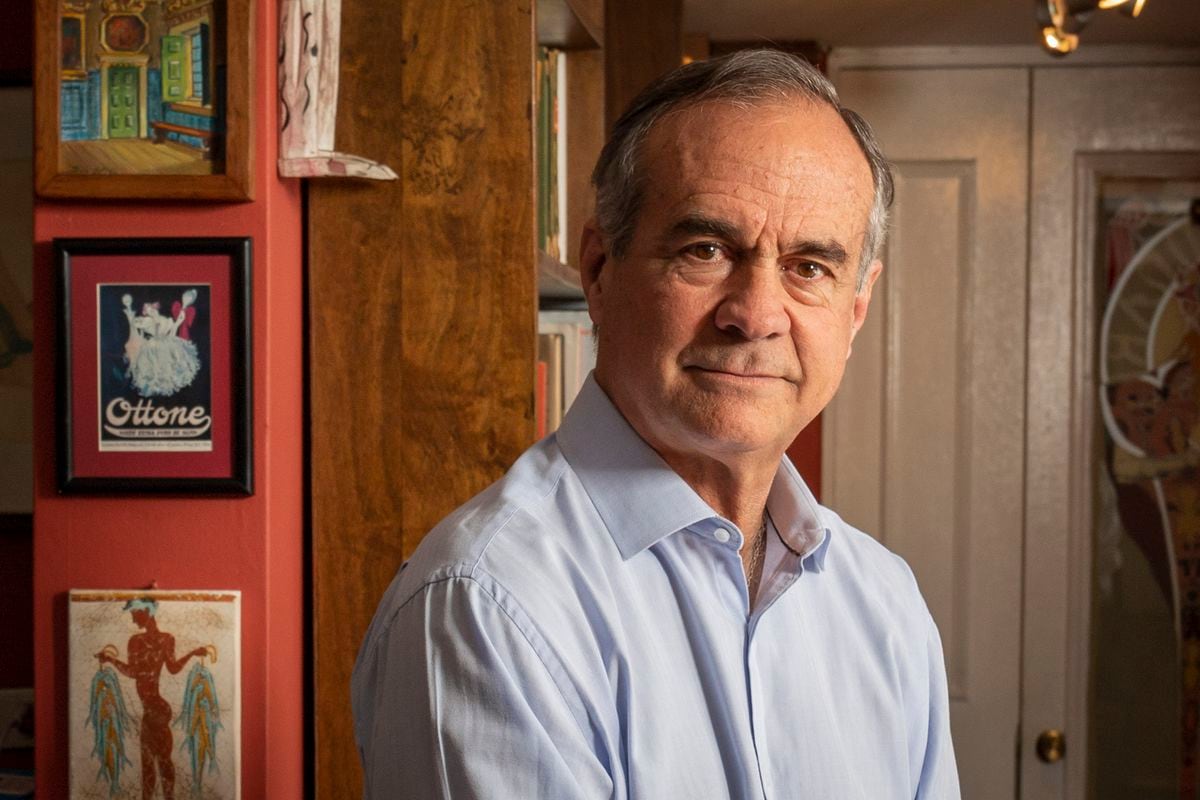

For Eugenio Tironi, a doctor in sociology and Director of Communications for the government of President Patricio Aylwin (1990-1994), in the Constituent Assembly "every call for moderation was destroyed."

"Here we went from a paper to a Constitution without political, historical or ethnographic mediation," explains the academic from Santiago.

Tironi maintains that several of the points that generated scandal —such as the decentralization of the State or the recognition of indigenous peoples— would have had a greater acceptance if they had been incorporated with “more measure”.

The sociologist also explains that it is necessary to understand the different historical moments in which the plebiscites took place.

The process that led to the approval of the Constituent Convention was born from the riots of 2019, the largest in Chile's democratic history, which gave the university left legitimacy as a political actor.

But between then and 2022 there was a pandemic and presidential elections (in which the extreme right of José Antonio Kast won in the first round);

In addition, insecurity worsened and the economy experienced a significant deterioration.

The climate was different and the left was not aware of it.

"The conventionalists were not sensitive to this change in public opinion and embraced the causes that had put them in the convention," explains Tironi, who describes this behavior as a sign of political inexperience.

The result of the plebiscite was a bucket of cold water for the left.

Mandatory participation was applied for the first time and the result revealed a "disconnection with the real Chile," according to Ascanio Cavallo, a journalist, political analyst and member of the Chilean Academy of Language, via videoconference.

While the country was going through a state of "semi-recession" and the concerns of the common citizen were focused on the lack of employment and the cost of living, the Convention had, according to Cavallo, other concerns, "very student, very upper classes".

That is why the analyst is not surprised that the majority of the votes against the Constitution have come from the poorest sectors of Chilean society.

More information

Gabriel Boric's generation deals with its first major defeat in charge of Chile

In the ranks of the left, the story has become popular that the victory of Rejection was the result of false news and fear campaigns from the right that predicted the transformation of Chile into another Venezuela.

For Cavallo, however, it's time for them to accept defeat: "I think they have to explain something they don't understand and still don't understand."

When the numbers show such a clear difference, the

fake news

argument loses steam.

The left failed in this first attempt to bury the 1980 Constitution, that vestige of the military dictatorship, but its fight is not over.

The president has confirmed the beginning of a second process, since the people's mandate to come up with a new text is still in force.

The left should, perhaps, take the path of moderation, get closer to the concerns of citizens and not repeat mistakes.

“Chile does not need any winger and Boric must be a president of that medium.

It is difficult to do it when you have criticized previous governments for doing just that”, explains the philosopher Aurenque.

Boric is no longer a student leader, he is now the president and must deal with the realities of politics.

The replacement of key figures in his cabinet —giving space to traditional Concertación policies— and the first approaches to the center are the sign of a change, but convincing the opposition will not be easy.

“In Chile I see very little generosity from side to side.

As citizens we must demand more of that political greatness.

Make real politics and not just opportunistic attacks”, says the thinker.

As Boric began to search for that “middle path”, student movements started new protests and took over subway stations in Santiago.

Thus, as one of those students, Boric was a few years ago: demonstrating in the streets and demanding a better country.

Now, as president, he must govern both for them and for that 62% who voted against the Constitution.

With a fractured country, he is obliged to aim high and has to aspire to build, as Patricio Aylwin said in 1990, "a Chile for all Chileans."

Sign up for the weekly Ideas newsletter

here .

Subscribe to continue reading

read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber