As with doping in other sports, science is ahead of the law in cheating in chess with the help of powerful computers.

Reigning world champion Magnus Carlsen has scandalously insinuated that 19-year-old American Hans Niemann played dirty to beat him.

The accused admits that he did it between 13 and 17, but not now, and the Norwegian has not provided a single solid indication.

Cheating already existed in the 18th century, and everything indicates that it will increase when the chips are connected to the brain.

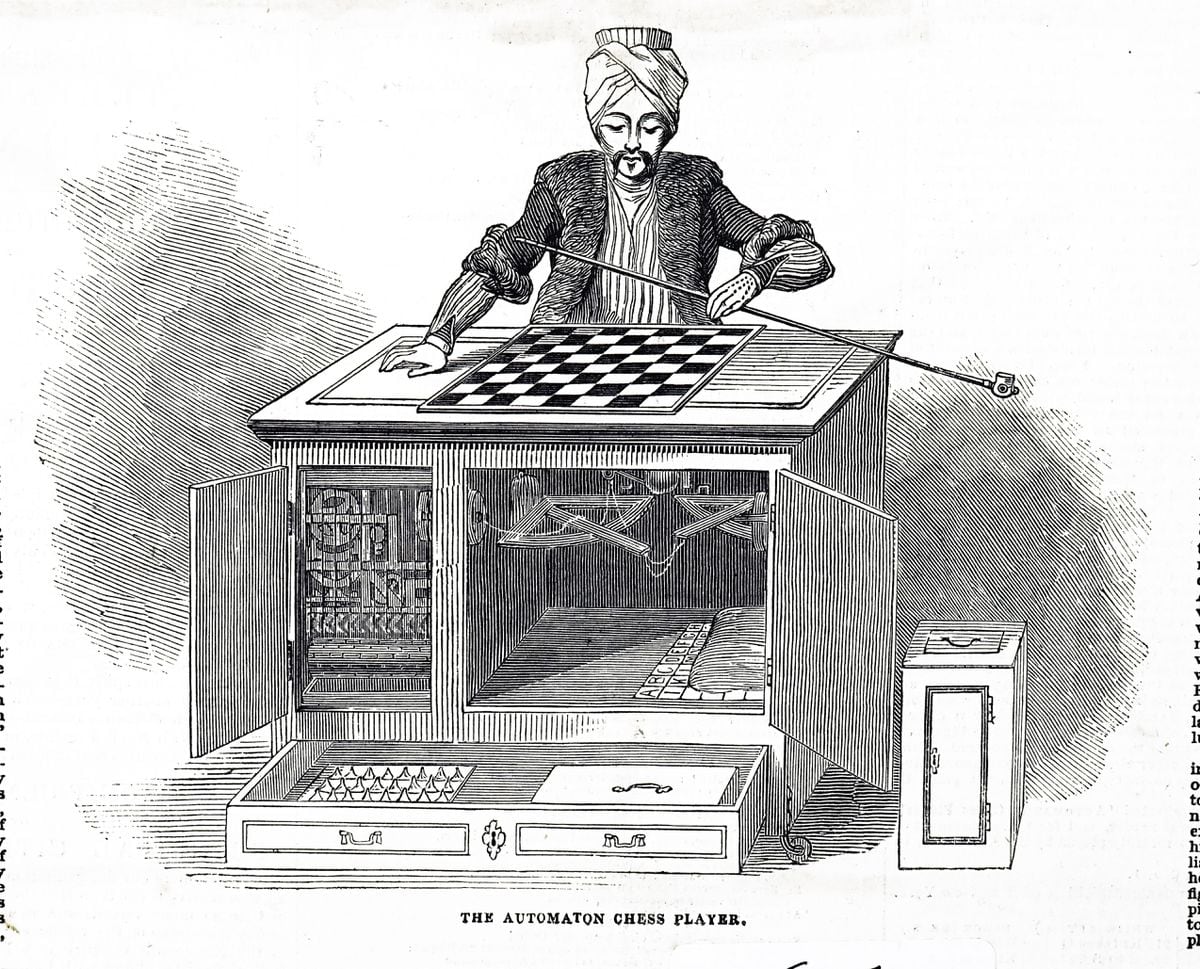

If the renowned Austro-Hungarian engineer and inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen (1734-1804) were to rise from his grave today, he would probably smile with great satisfaction at the Carlsen scandal.

Especially in its most jarring branch, supported by magnate Elon Musk (Tesla): Niemann would have used anal devices, connected to someone who was following the game live on the internet with the help of computers that calculate millions of moves per second, so that tell him what his best move was.

Such eccentricity is technically possible, but absurd, because the same thing could be achieved with a simple micro-earpiece hidden in Niemann's ear that would easily pass through the metal detectors used by referees at major tournaments.

Why would Kempelen, to whom Edgar Allan Poe dedicated an essay, feel a boost in his self-esteem?

Because his showy machine,

El Turco,

dressed in Turkish clothes, was all the rage playing chess in various European courts, where he defeated Napoleon and Catherine the Great, among others.

And later, on a tour of America with the late Kempelen, Benjamin Franklin and many more.

The trap was a very short, high-level chess player hiding inside.

It was not discovered for decades by the great intelligence of Kempelen, who, thanks to a precise set of mirrors, opened the doors on the four sides of the machine without seeing anything suspicious.

And he lit candlesticks on top to hide the smoke from the candle that illuminated the hidden player.

With the technology of the 18th century, only such clever tricks could make a machine play chess.

With the one at the beginning of the 20th century, and without any ruse, it was partially achieved by the engineer Leonardo Torres-Quevedo (1852-1936), one of the most brilliant Spanish scientists in history -he also invented remote control, balloon technology Zeppelin and the ferry used by tourists in Niagara Falls -, despite the fact that very few Spaniards know who it was.

His automaton, which perfectly gave the checkmate of rook and king against king alone, is preserved (but has not been restored) at the Polytechnic University of Madrid.

Three quarters of a century later, in 1997, an event occurred in New York whose importance far transcended the field of chess.

The 2nd game of the 2nd duel was played between the world champion, Gari Kasparov, and the

Deep Blue

computer , from IBM, defeated by the Soviet one year before in Philadelphia (2-4).

The silicon chess player was attacking the human, who was preparing to counterattack.

And suddenly, the machine did something amazing, which left those of us who were following the fight from the press room dumbfounded: instead of continuing its offensive, it inserted a blocking movement to prevent the counterattack.

That's what an elite human player would probably have done in a reverse situation, but never an inhuman until then because that way of

thinking

it was inconceivable on a machine.

Kasparov suffered at that time one of the greatest traumas of his career.

He accused IBM of cheating with human intervention at the key moment in that game, which he lost.

The duel was even (2.5-2.5) in the sixth and last round, but the champion was unhinged and lost again, with a game unbecoming of his genius.

The news went around the world, IBM shares skyrocketed, and Kasparov made a fuss during the final press conference, insisting on accusing him and demanding a duel of rematch that he never got.

Kasparov, during one of his games with Deep Blue in New York, 1997Reuters

Ten years later, around 2007, there was no longer any doubt that the best chess player in the world was made of silicon.

That scared a lot of people, because of the prospect of machines taking over the world, but human and computer chess coexisted well, like athletics and cycling or motorcycling with Formula 1. Also, what IBM learned with Deep Blue to bring down Kasparov was later applied in very important fields of molecular calculation (manufacturing of complex medicines, weather forecasting, agricultural planning...).

However, a worrying problem arose, one that jeopardized the future of chess as a sport: cheating with the help of very powerful computers.

A player calling himself John Von Neumann, after the famous Hungarian mathematician who died in 1957, had rocked the 1993 Philadelphia Open with a disturbing scandal as he alternated beginner's mistakes with royal wins over favorites.

In reality, he was an impostor and provocateur: he didn't even know the rules, but he was connected by a small headset with a friend and a computer installed in another room.

The deception was discovered because communication glitches sometimes caused awful plays.

Thus arose the ban on entering the gaming room with a mobile phone and the need for referees to scan the body of each participant at the entrance of important tournaments, among other measures.

Since then there have been many players punished in virtual chess clubs on the Internet, who have developed algorithms to catch cheaters: if their moves coincide in a very high percentage with those that the machines would make, it is assumed that they are cheating.

But never before has there been a case in the world elite, because the chess stars, who earn more than enough money for a very pleasant life, know that their career would end immediately if they were caught cheating.

The closest thing happened at the Janti Mansiisk Chess Olympiad (Russia, 2010), where a member of the French team, Sebastian Feller (today he is the 435th in the world), received help through the sign language of his captain, Arnaud Hauchard , who in turn was connected to a buddy in France who followed the games live.

Niemann looks at Carlsen during the game between the two, on the 11th, at the Sinquefield Cup in San Luis (USA)Lennart Ootes

Until the Niemann case has arrived, whose last name resembles by pure chance that of the famous Neumann.

The young American, who had already beaten Carlsen in the rapid game tournament in Miami in August, did it again in September, but this time in one of the biggest (slow game) competitions of the year, the Sinquefield Cup in San Louis (USA).

The world champion reacted in an unprecedented way, withdrawing from the tournament -he had never done it in his life- and without giving explanations;

he only added to his tweet a video of soccer coach José Mourinho in which he says: "I don't speak because if I do I will have serious problems."

But the organizers made it very clear that there was an implicit accusation of cheating by immediately decreeing that, from the next round,

From there, the scandal in social networks and the media has been enormous, and fueled by two other very striking events.

Niemann admitted in an interview with Chess24 (online chess platform whose main shareholder is Carlsen) that he had cheated in online games between the ages of 13 and 16, but not afterwards ("I learned my lesson") and never in face-to-face games. .

And when it was time for them to meet again, in a quick online tournament organized by Chess.com, which Chess24 bought two months ago, Carlsen again did something very unsportsmanlike that he had never done before: surrender to Niemann after making a single move.

Most grandmasters who have weighed in, including former champion Gari Kasparov, demand that Carlsen explain rather than throw the stone and hide his hand.

The Norwegian has not said anything substantial up to the time of writing these lines, but perhaps he will from this Sunday night, when he finishes the final of that tournament against the Indian Arjun Erigaisi.

Meanwhile, a legion of fans of the Scandinavian show a blind trust in him and in his veiled accusations, despite the fact that his behavior is very close to slander.

Beyond the moral background of the matter, this scandal is only a foretaste of the great leap forward: experts say that our brains will be connected to a chip, or have one inserted, within ten years.

It will be a major change in our lives and a breakthrough in many areas;

for example, in disease prevention.

But it will end chess as a sport unless referees can deactivate that chip for the duration of games.

In any case, these enormities will have a logic and will not reach the point of absurdity, as happened a few days ago, when Niemann, faced with accusations of having put something in his anus, said: "I am willing to play naked."

Subscribe to

the weekly newsletter 'Wonderful play',

by Leontxo García

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/KMEYMJKESBAZBE4MRBAM4TGHIQ.jpg)