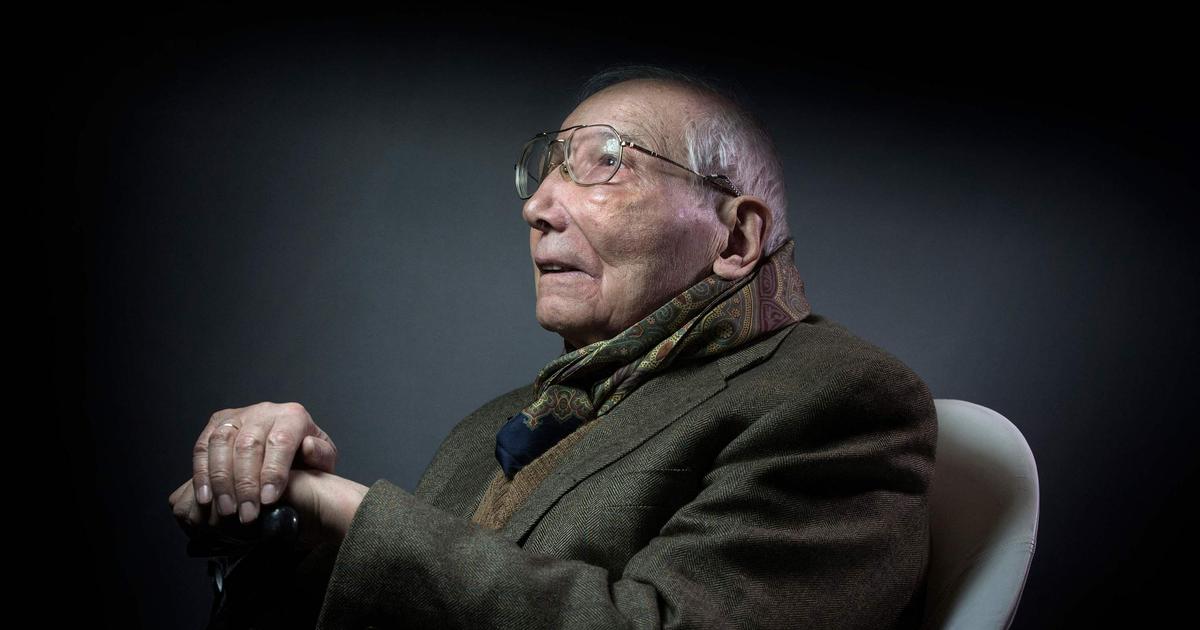

Loris Chavanette is the author, in particular, of

Quatre-vingt-quinze.

The Terror on Trial

(CNRS editions, 2017, preface by historian Patrice Gueniffey), thesis prize from the National Assembly 2013 and history prize from the Fondation Stéphane Bern-Institut de France 2018, and from

Danton and Robespierre.

The shock of the Revolution

(Pasts compounds, 2021).

He also established the edition of a selection of Napoleon's letters,

Napoleon.

Between eternity, the ocean and the night.

Correspondence

(Books, 2020).

Plato writes that parents are reborn through the children they produce.

The same goes for writers, except that children are their books.

Through them, their thought continues to float in our consciousness, to the point that their presence is still felt after their death.

This is the case with Paul Veyne, who left on September 29 at the age of 92, leaving us an abundant body of work.

The historian from Aix-en-Provence, who became famous for his works on Greco-Roman antiquity, including

Le Pain et le Cirque

(1976), and

When our world became Christian

(2006), have remained models of the genre, with this delicious mixture of erudition and irony.

A committed historian too, when the world yielding to bewilderment in front of the images of Palmyra dynamited, ravaged, martyred by Daesh's soldiers of death, took up his pen to offer a meditation on the beauty of the ruins of the ancient city in being reduced to ashes.

With his story of Palmyra la belle, Paul Veyne breathed new vigor into this treasure of the civilization he had loved so much, and to which he continued to give flesh through the refinement of his thought.

His peers, or rather one should say his successors, covered him with honorary rewards, to thank him for having been able to carry our language so high, that is to say so original, for decades.

Paul Veyne deplored this fashion for the erased historian, with marmoreal erudition, devoid of candor and intuition.

Loris Chavanette

What is less remembered about his work are his reflections on the art and manner of writing history.

Never have works of methodology and epistemology been so pleasant to read than from the pen of Paul Veyne.

I remember that, for the preparation of a symposium in Rome on the writing of history under the French Revolution, I had immersed myself in his essays of the genre, and in particular

How one writes history

(1971).

Paul Veyne showed himself there annoyed by the wave of positivism breaking over historical thought, because of a history that had become essentially academic, the Sorbonne remaining the parent company of this current which Paul Veyne criticized for lacking imagination and , by dint of compiling sources and documents, of missing the essence of the profession of historian according to him, namely to trace the part of mystery and intrigue which the actions of men and civilizations of yesterday are by nature impregnated.

Also, against the assumed method of coldness of the positivist historian, the latter gloating in

"erasing himself before objectivity"

, Paul Veyne deplored this mode of the oblivious historian, with marmoreal erudition, devoid of candor and intuition, in short a sort of Leviathan of historical thought giving birth to a neutral, odorless, supposedly scientific truth, subjectivity being inevitable.

Paul Veyne paints the portrait of the modern historian according to him:

“all he has to do is report the facts, either as a

'reporter'

or as a compiler.

For this he does not need dizzying intellectual gifts;

it is enough for him to have three virtues which are those of any good journalist: diligence, competence and impartiality.

To the detective historian that the university creates, Paul Veyne, product of the École Pratique and the Collège de France, of multidisciplinary research, of the meeting of methods and knowledge, advocating myth as an object of history and the literature as marginal historical truth, opposed the wandering historian, the one who ventures on poorly marked paths, steep paths, skirting precipices, like Shakespeare's King Lear, to inhale the ocean vapors rising from the abyss, because it that is where the inspiration is.

The historian must become as poet as philosopher, an idea that Paul Veyne shared with Paul Ricœur, or even Michel Foucault, borrowing from the latter this warning to the young historian, with the flavor of an adventure:

"Let no one enter here unless he is or becomes a philosopher.

In what is undoubtedly one of his most moving books, he shocked by entitling it: Did the

Greeks believe in their myths?

If the positivist historian does not ask the question at all, the magic of Veyne is to ask it for the essential reason that everything is matter for reflection, for questioning, the worst being to build a system of methodological truth from which the thinker could not leave without being murdered for defect of form, defect of procedure, lack of understanding, or, worse, for sin of imagination.

What Paul Veyne reveals to us is that in reality the pious scholars of positivist history are infinitely more pretentious than the writer-historian, adventurer, who prefers to pose problems rather than prove solutions.

Loris Chavanette

In a note to

Memoirs from beyond the grave

, Chateaubriand criticizes the biography that Walter Scott devotes to Napoleon, on the grounds that he is sorely lacking in imagination and in the name of impartiality, did not know how

to "stand up to his hero, nor look him in the face.”

Ultimately, too much reason kills judgment for the romantic.

Certainly, we know from Herodotus that the word "Historia" comes from "Inquiry", but the investigator should not capitulate or bow to the source, because this depends to the end on personal interpretation, because science without conscience remains ruin of the soul.

What Paul Veyne reveals to us is that in reality the pious scholars of positivist history are infinitely more pretentious than the historian writer, adventurer, who prefers to pose problems than to prove solutions, because the latter alone has the modesty to believe that there is not a single truth, falsely presented as objective, but an infinity of ways of thinking, because there are a thousand ways of being in the world, especially in a world in perpetual movement.

Those attached exclusively to the document and, like Saint-Thomas, believing only what they see, are ultimately more to be pitied than those who, like Paul Veyne, had the humility to write:

"

'truth'

wants say many things… up to encompassing fictional literature.”

What does it matter, in the end, whether the Greeks really believed in their myths or not, what matters is to ask oneself in complete freedom, in complete independence, for pure pleasure.

Paul Veyne was the art of enchanting history by accepting its share of equivocation, which goes hand in hand with its necessarily fallible human part.

Fortunately fallible, one might say.

And in this sense, the spirit of Paul Veyne will continue to flow through our veins, despite the disenchantment of history to which the modern triumph of cold-blooded experts condemns us.