Today marks ten years, one month and two days since September 4, 2012, the day Santos announced on television the start of negotiations with the FARC.

In these ten years, everything has happened: the distrust of citizens in the process, which many saw (with the reason given by the precedents) as a future disappointment, one more in the string of disappointments that the peace processes had been from this country;

the distrust of the negotiators in the citizens, or in what is called public opinion, which we saw march at the pace that the lies, distortions and deceptions of a part of the opposition put on it;

the normal and predictable mistrust of the negotiators among themselves, since it was a question of breaking with decades of misunderstandings and clumsiness and intransigence and deafness, and each failure cost lives.

And it was different, yes: but not only for good reasons.

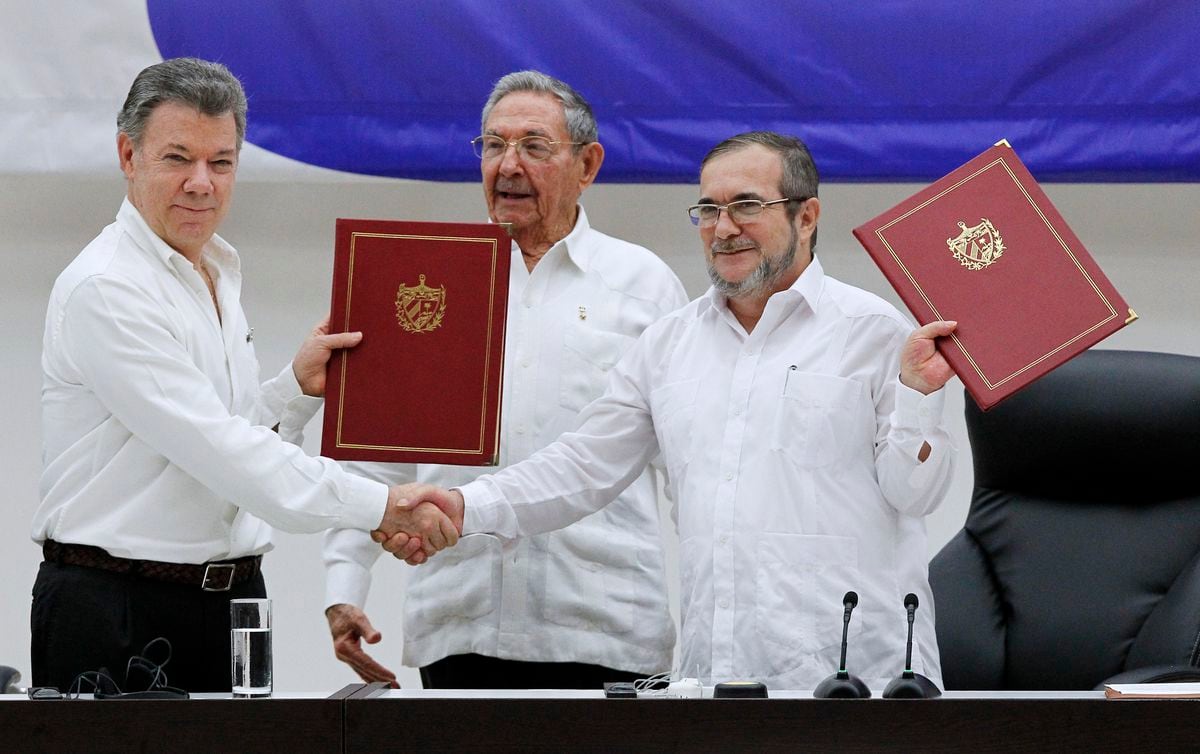

Government negotiators had met with the FARC for six months in secrecy, but at the end of August, when the general agreement was signed in Havana, the news was leaked to the media: it was reported by Telesur in Venezuela and by RCN in Colombia.

Santos was forced to watch two minutes of television in which he confirmed the conversations, explained some things and clarified others, and then came the reaction of Uribe, who said without shame (and without knowledge, and without information) that this was nothing more than a "legitimation of terrorism".

(That day came to mind recently, with the reactions to the Truth Commission report: they raved about the thousand pages of Findings and Recommendations just 15 minutes after the presentation at the Jorge Eliécer Gaitán Theater.) Uribe,

Of course, it was the same president who, shortly before the end of his government, had invited the FARC to a secret meeting in Brazil: a meeting with an "open agenda" to try to make peace.

Hypocrisy and double standards were always one of the most notorious traits of the former president, but this was already a caricature.

Of course, Uribe was setting up his new party – the one called Puro Centro Democrático, which soon ended up losing the “pure” part: refrain from making bad jokes – and he needed a clear story and a specific enemy.

The announcement of the negotiations gave him everything and he gave it to time: his simple existence was almost a government program with which Uribe and his people would try to make him president again.

Although speaking of a government program is perhaps too generous: what Uribe set up with his party was a mere vehicle for the campaign for the No, which changed any government program due to the exacerbation of resentment, hatred, economic insecurities and physical fears of Colombians, to the point of getting them to go out

and vote for boars

.

It is too late to ask ourselves what country we would be now if one of our most influential politicians had not invested his enormous leadership in dividing us and alienating us.

But what happened happened: the No won, the negotiators came back to the table and ended up accepting 56 of the 59 No proposals. Today I am happy about that, because the result was better agreements: more inclusive agreements, the result of more negotiation. wide with more actors.

That is, after all, democracy.

(That's why it seems to me that it can only be the result of ignorance, misinformation or bad faith, or sometimes of all three things together, the idea, which still swarms out there, that the government made a rabbit out of the Colombian people. Please, be serious: a majority rejected the Havana agreements, and what there is now are not those same agreements approved through trickery, but corrected agreements, the result of a new negotiation in which that majority was duly represented by the same people which he believed at face value to vote for the No.)

But I digress.

What I want to say is that these ten years have been a long and difficult road.

It was difficult to find the words to explain what was happening in the negotiations;

it was difficult to convince the citizens of the virtues of a negotiated solution, and to achieve, through a precise lexicon, that it was well understood what caused reluctance.

The only thing the accords have had irrevocably on their side – these accords admired around the world and vilified here – has been time.

And it is a good ally: over time it has been seen that the slanders of the opponents were just that, slanders;

and nothing has happened that, according to their threats, had to be feared;

and neither has private property disappeared, nor has the Catholic family disintegrated, nor have the FARC taken power.

Instead,

For all of the above, it seems to me that Petro is wrong with the project that his government has ambitiously called

total peace .

.

The way in which the government has raised the matter, calling the criminal gangs and those who betrayed the agreements of the Teatro Colón at the same time that it calls the ELN, mixing apples and pears in a kind of mental hodgepodge that seems thought without patience, with ideas confusing and even more confusing language undermines the delicate logic that allowed the process with the FARC to settle slowly in the consciousness of Colombians.

The 2016 agreements were achieved after overcoming obstacles that most are not aware of, but one of the most obvious was a question of vocabulary: convincing Colombians that there was an armed conflict in Colombia, contrary to denial theses and a bit silly from the opposition, it cost pedagogy and arguments, and above all it cost time.

Using the vocabulary of the agreements to talk about these new conversations, whose actors are not politicians and cannot be treated like that, is seriously confusing citizens, just as it is confusing them to treat a criminal policy problem as a peace negotiation.

(For example, a gang does not demobilize: it submits to justice. I also fail to see how one can speak of a "cessation of hostilities" with organized crime. Words matter, and it matters to name things precisely, because that is the (The only way for society to take ownership of the peace story. And we need it.) In short, confusion can rob the implementation of successful agreements that we already have of energy, focus and resources – always limited – that are still needed to bring them to fruition,

or to neutralize the attacks they received for four years.

This is not the time for mistakes.

Subscribe here

to the EL PAÍS newsletter on Colombia and receive all the key information on the country's current affairs.

Register for free to continue reading

LOG INSIGN UP

Or subscribe to read without limits

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/K3P4376UVR26FWBFTPAU4UMSUI.jpg)