Calle de Antonio Cavero, 37, Madrid, October 28, 1982, 1:00 p.m.

Julio Feo put his scarf around his neck —with that flirtatious carelessness that over the years would become famous among the Moncloa covachuelistas—, he put on his jacket and, with the car keys in his hand, left the house.

He greeted the policemen at the door and walked slowly through that neighborhood of lackluster chalets.

He hardly passed anyone until the place where he had parked, a few streets in the neighborhood.

They had agreed that a traffic of cars at the door would attract the attention of the journalists.

He started up and headed to the other side of Madrid, precisely looking for a journalist, the only one who would be allowed to witness that afternoon and tell about it in a newspaper.

José Luis Martín Prieto waited impatiently on the corner of the meeting, and when Julio picked him up, it seemed to him that they were traveling very far, to the outermost regions.

The driver took so many turns to throw him off the track that Martín Prieto didn't know if it was to the north, to the west, or to the east.

He had carried too many kilometers in his body.

He had covered Felipe's entire campaign, embedded in his bus with a small band of chroniclers.

When dictating the texts to the editorial office of

El País

every night, it was difficult for him to know if he was in Cuenca or Badajoz.

His immersion in the political caravan had been so deep that he was beginning to show a certain Stockholm syndrome: Felipe and his team already seemed like friends to him, and that was dangerous.

When writing, he had to try very hard to keep his distance.

As soon as he entered the chalet, a robust and friendly basset hound received him as if he were from the house, sniffing him with confidence.

"His name is Pelayo," said Julio Feo, taking off his scarf and stroking the animal, which under his hands seemed like a fashion accessory.

Julio's daughter, his assistant, Piluca Navarro (Felipe's secretary), José Luis Moneo (Felipe's personal doctor, essential throughout the campaign to control his diet and send him to sleep), Juanito Alarcón with his wife and , of course, Felipe with Carmen Romero.

The press believed that the candidate was at his house on Pez Volador street or at the electoral headquarters of the PSOE, which Guerra directed, or at the party's headquarters.

No one suspected that he was hiding in Julio Feo's chalet, where he arrived after voting, avoiding the photographers.

There he waited for the results with no more contact with the outside than two direct telephone lines: one with the office of the Minister of the Interior, Juan José Rosón, and another with that of Alfonso Guerra in the electoral headquarters.

Otherwise, there was whiskey and liqueurs—champagne, no,

Martín Prieto was granted the privilege of spending the day with Felipe without any barriers or pressure: let him tell what he wanted.

During the campaign he had written a bunch of chronicles that were already part of the best political journalism ever written in Spain and that today are one of the richest sources for anyone who wants to know that time.

The one that he would write that afternoon, just before the closing of the electoral colleges, is entitled "Felipe González waits calmly at a friend's house" and would also deserve a place of honor.

With a very clean prose, more Anglo-Saxon than Latin —something very rare in Spanish journalism, which spills over to the baroque side—, he transmits something amazing: the domestic calm that precedes the greatest change in the history of Spain.

If Martín Prieto had not left that testimony,

It would be very hard to believe that Felipe González spent the day of his great victory taking a nap, smoking Canarian cigars, letting two ice fish melt in the whisky, caressing Pelayo and playing childish things with Julio Feo's daughter.

The document also has the value of being unique and definitive: there will never again be chronicles as close to a leader as Felipe.

From that day on, a cloud of cabinets and secretaries will protect you from direct contact with the pens.

Shortly after, Juanito Alarcón returned, having gone out to look for Pablo Juliá, the photographer who would illustrate the chronicle of Martín Prieto.

Juliá was the photographer for

El País

in Seville, but, above all, he was a friend of Felipe.

They met in 1967, when this one was already a labor lawyer who was messing around with the PSOE, and that one, a kid who studied Philosophy and Letters and hung around the assemblies.

Juliá had come to Seville from his native Cádiz and was poorer than the

Buscón students

of Quevedo, but he did not care.

He played politics without taking it very seriously either.

He was a communist, although not from the PCE, much more to the left, and he liked to annoy Felipe by calling him a bourgeois and a social democrat.

Far from getting angry, he acted as such with his friend.

One afternoon he learned that Pablo lived in the Vergara pension, a musty hole in the Santa Cruz neighborhood, and he took him out of there to install him, with Juanito Alarcón, in one of the apartments that his father had in Seville and reserved for his children. .

Without realizing it, he paid part of the tuition at the university (give me a thousand pesetas —he said—, I'm going to fix Carmen [Romero]'s tuition and I'll pay yours by the way, and Pablo didn't know that the tuition cost much more than a thousand pesetas, which Felipe paid) and I brought him clothes without hurting his pride (my brother-in-law doesn't like this sweater,

In those years, Felipe was more than a friend to him.

He was almost a mentor and, of course, a protector.

That is why it is Juliá who provides the best and most convincing testimonies of felipista honesty.

One day, Felipe stopped by the apartment to eat something with his two friends, and they took out some cans of pickled partridge.

From the way they looked at each other, Felipe understood:

"You stole it, right?"

As poor left-wing students, they stole things all the time and silenced their guilt by saying that they were stealing from the Franco regime, that they were acts of sabotage against a dictatorship.

Philip was very angry with them:

—A socialist doesn't steal, damn it.

Nobody, nothing is stolen from anyone.

Already then, Pablo Juliá was a socialist, although a little reluctant.

He lasted in the party as long as he was in hiding.

In 1976, on the eve of the first congress in Spain, Alfonso proposed him as freed, that is, paid by the party, so that he could dedicate himself entirely to politics.

Felipe didn't like it.

He invited his friend to eat and told her:

—Pablito, you're not good for this.

Dedicate yourself to photos, which you're not very good at either, because I take photos better than you.

You're not good for politics, you're too naive, you can't stand what you have to put up with here.

Pablo forgave the brutality of the felipista words, to which he was accustomed, he agreed and became one of the few Sevillian friends from the times of the underground who did not make a political career.

Also, one of the few old friends whose friendship has never been clouded by ambition or conflicts of interest.

A friendship that remains today and that, on October 28, 1982, opened the door of Julio Feo's chalet to make history with his camera.

Alfonso Guerra raises the hand of Felipe González, both leaning out of a window of the Palace hotel in Madrid, celebrating the historic victory of the PSOE.César Lucas

A few years earlier, in 1974, Pablo had signed one of the most famous stamps in the history of the PSOE: the photo of the tortilla, a souvenir of a picnic on the outskirts of Seville with Felipe González, Alfonso Guerra, Luis Yáñez, Manuel Chaves , Carmen Hermosín, Carmen Romero and other young Comanches from the PSOE, all ready to attack Suresnes.

The photo is actually titled

Oranges

Well, that's what they're snacking on.

Before that, in 1968, he made one of the best portraits ever made of Felipe: in his house in the Bellavista neighborhood, in the summer, a very young González leans on the hood of a car.

He's wearing a short-sleeved plaid shirt and smoking what's left of a cigarillo, almost a butt.

He doesn't seem to realize that he is being portrayed.

Watching for something out of frame, he half-smiles with half-closed eyes.

It's rare to surprise him so carelessly.

That day at Julio Feo's house, Pablo again managed to get a couple of intimate smiles out of him.

The great socialist boss is reclining on a sofa.

On the right he holds a small glass, and with the left he hugs Vanessa, the girl from the house, with whom he has been playing.

She is her, going to set the table, she asked:

"How many will we be?"

Philip replied:

—Two hundred in Congress and eight to eat.

At the table, the candidate took the measure of the discretion with which he faced his new life:

—I had to get rid of the entire Socialist International.

Not Brandt, not Mitterrand, not Soares, not anyone.

It has been difficult to convince them that you should not celebrate much, that you have to be discreet.

That bastard Rosón has asked me to control the street tonight.

What nose do they have?

They have already resigned, we have to do their job, as if we were already governing.

Not only did he disown champagne because of the price, but also for fear that its uncorking would incite the military to respond with live fire.

The country still had the cold of the blow in its bones.

Nobody knew it in the chalet, except Felipe: military intelligence had disarmed an attempt for the day before.

They had a plan to blow up the elections with a very bloody operation that included the assassination of politicians and the seizure of the Zarzuela Palace, so that the king could not repeat his speech on February 23.

Every once in a while, they would surprise a plot, which was good and bad at the same time.

Well, because its detection meant that the seditious military were becoming less important and had less operational capacity;

bad, because there was still too much coup in the barracks.

Felipe had promised a sober celebration,

After the disappointment of 1979, no surprises were expected in the count.

Alfonso had done his calculations well and the campaign was an unqualified success, full after full in all the provinces.

Julio Feo asserted his thesis that the elections had already been won since 1979 and that the campaign's job was not to lose them.

The electoral experience of other countries indicated that the favorite candidate was wearing down with exposure in the campaign.

It is usually good for the second-placed to go out to give rallies, because he can trace his intention to vote in them, but whoever starts with an advantage must take great care of his image so as not to lose voters along the way.

It was very difficult to add more seats than expected by the polls, but a bad campaign could cause them to lose many.

Therefore, the job consisted of propping up the experienced Felipe,

to Felipe heir to a democratic tradition, to the leader capable of taking the country forward.

In a colloquium on Televisión Española, days before the start of the electoral campaign after the elections were called, the director of

Cambio 16

, José Oneto, asked him about the electoral slogan, "For change."

"What does this change consist of?"

-She said.

Felipe thought about it a bit, maybe really, looking for some words that he had not negotiated with his team, and answered with a second motto:

—That Spain works.

He could have left the answer there, but he had already gained momentum and he didn't know how to repress the explanation that rounded it off.

After a couple of detours through the hills of Úbeda, she quoted her friend Olof Palme:

—Some Portuguese told him that they wanted Portugal to stop having rich people.

Palme told them: "I want Sweden to stop having poor people."

I tell you: I want Spain to stop having misery.

I am not against anyone.

What I want is for there to be no marginalization.

It was there, they had it.

The candidate nailed the message that some Spaniards wanted to hear, fed up with nothing working, self-conscious about an endemic backwardness and disenchanted with a democracy that was not quite noticeable in daily life.

From that moment on, Felipe only had to walk the phrase through Spain like an athlete carrying the Olympic fire.

Let Spain work.

The whole effort was to keep it from going out.

And it didn't turn off.

They took her turned on to Julio Feo's chalet, at number 37 Antonio Cavero street in Madrid, where she warmed up the after-dinner while Pablo Juliá took photos and Martín Prieto wrote down in his notebook.

At a quarter to nine, forty-five minutes after the schools closed, the phone on the secure line with Guerra rang.

Julio Feo took it.

Alfonso's voice on the other end said:

"Put me through to the president."

-What's happening?

Philip said.

"President," Guerra announced, emphasizing the position for the second time, with the hyperbole of a classic actor that he always cultivated, "the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party has obtained two hundred and two deputies."

Carmen, Julio and the others, who were glued to the phone, heard Alfonso and jumped for joy, with shouts and tears.

Everyone hugged, jumped and cheered, but Felipe hung up without flinching.

The others, taken aback by the boss's unruffled calm, calmed down as well.

Julio confessed, almost in whispers, that he had a few bottles of champagne in the fridge, despite the prohibitions, and suggested that perhaps this was the moment to open them.

"No champagne," Felipe said;

if anything, a glass of wine, to toast.

But quickly, you have to prepare for tonight.

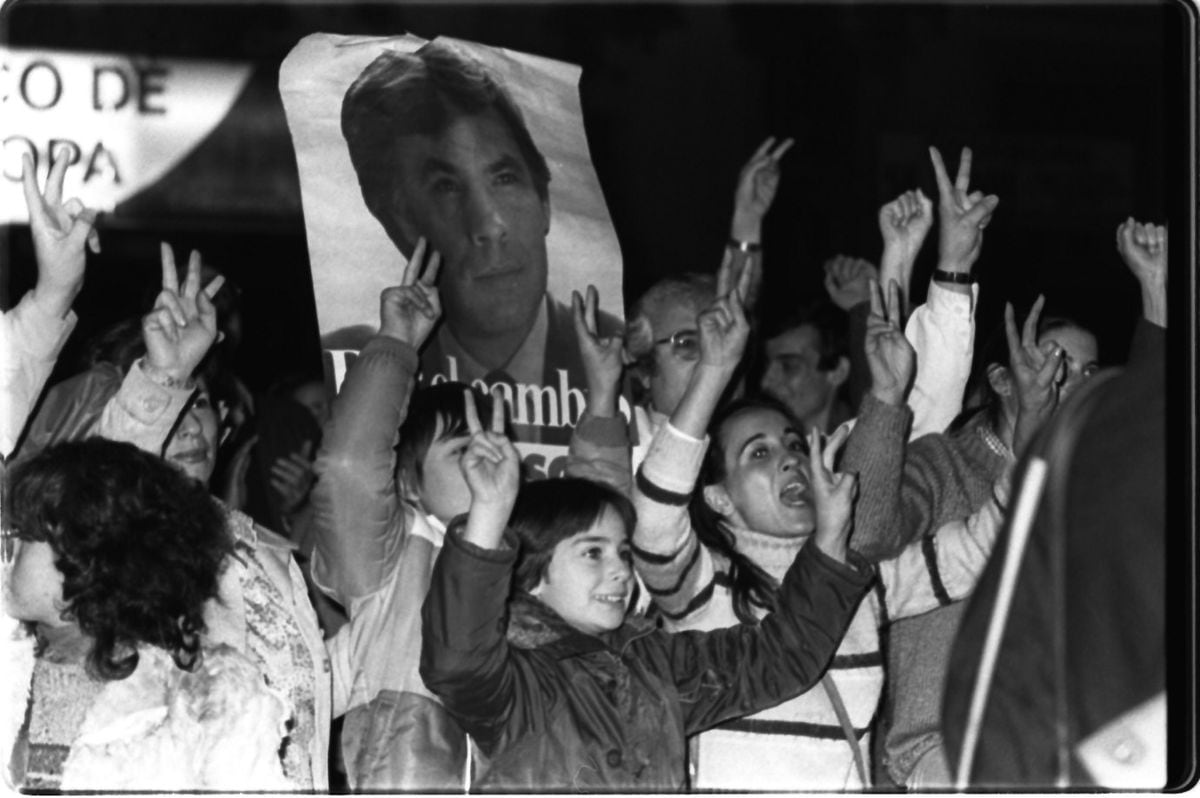

Felipe González greets surrounded by supporters at the Palace hotel after the victory of the PSOE.

This image was the cover of EL PAÍS the day after the elections, on October 29, 1982.CHEMA CONESA

The photo for history was not made by Pablo Juliá, who has always worked on a more important record, that of intrahistory.

The testimony that would illustrate encyclopedias and high school history textbooks was the work of César Lucas.

Before midnight, Alfonso and Felipe leaned out the window of a suite at the Palace hotel and greeted a discreet crowd chanting Felipe's name.

The two friends shake hands, raising their arms, united in a triumphant gesture.

It is not a big thing.

An austere icon for a night in which very few got drunk.

I have written

the two friends

and I have written well.

At the close of that 1982 campaign, at a large rally in Seville, Felipe referred to Alfonso as "my soul friend, my forever friend."

Most exegetes, public and private (that is, those who tell anecdotes about the president with the request that it not be known that they have disclosed them), maintain that they were never friends, and that their relationship was political, not political. intimate.

They attribute the confession at the rally to the exaltation of the moment, but I think they are wrong.

That they did not share intimacy does not mean that they were not united by a deep friendship.

That photo is the portrait of two friends in the sweetest moment of their friendship.

The enthusiastic socialists huddled between the Plaza de las Cortes and Plaza de Neptuno soon dissolved, and the Palace employees did not have to make much of an effort to control the revelry in the salons.

No one trashed the suites, and no one had to call the police to bring order.

Nor did the feared fascist pickets appear.

The night ended very discreetly, in the

El País

building on Miguel Yuste street, at a late dinner with the director of the newspaper, Juan Luis Cebrián, the owner, Jesús de Polanco, some journalists and some other famous columnist, like Francisco Umbral, who remembered Felipe «with long hair and boots, without a tie, and sat down with his legs crossed, smoking a Fidel cigar».

He wrote this portrait long after that dinner, when Threshold was no longer working for

El País

nor for the felipismo, but on the contrary.

"From the balcony of the Palace to the dining room of

El País

," he concluded, "two areas of historical liberalism."

A new power settled in the interiors of Madrid and drew routes between newsrooms, government palaces, intellectual halls and shareholders' meetings.

That night a symbiosis destined to change the Spanish landscape was born.

The newspaper that aspired to represent democratic Spain declared itself, like more than ten million voters, felipista.

Two journalists from

El País

accompanied Felipe in his political climax, and the same newspaper was in charge of giving him dinner and toasting with him, perhaps without pretense, to a full laugh.

In the adjoining building the copies announcing his victory were printed, and the noise of the presses would muffle the applause of the toasts, in case they disturbed the broadswords.

The headline on the front page was the most insipid, in tune with the discreet air that everyone was looking for: «The Socialist Party, with 201 seats [

sic

, were 202, but the last seat was assigned when the newspaper had already closed the edition ], obtains the absolute majority to govern the nation».

Diario 16

, sponsored by

Cambio 16

, where Felipe had found his first friends in the press, was much more celebratory: on a full page and in capital letters, it read "PRE-SI-DEN-TE."

Julio Feo and Juan Tomás de Salas, the owner of Grupo 16, had their differences since the time when he worked in an office in Pareda with the

Cambio

newsroom , and they were used to asking each other for favors that were later not done.

For example, Julio would write a cover for his candidate, and then they would put it out on the inside pages, giving the cover to Fraga or to someone else.

Or the other way around: from the newsroom they asked Julio for an exclusive, and then he gave it to another medium.

Perhaps that forged a distance that led Felipe to approach

El País

, which then fell into the hands of the Polanco family, after a few years of very divided shareholding, with representatives of many economic and political interests.

Nor should we forget that Enrique Sarasola, a close friend of the already president, was one of the founders of

Cambio

.

The PSOE could not move away from that nucleus of journalistic power and approach another without raising treason alarms).

In five columns, the cover of

El País

was illustrated with a landscape photo of the new president making his way between the public and photographers as he stepped down from the gallery at the Palace.

The hand of an enthusiast who greets him covers half his face.

Everything had changed, but he had to pretend that everything was still the same.

'A certain Gonzalez'.

Serge of the Mill.

Alfaguara, 2022. 376 pages, 21.90 euros.

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

Subscribe to continue reading

read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/45YBKTPDNNEPPK2E3GCF3LSJSI.jpg)