"We are asked if we are Thai, we are called Chinese, we are asked what we are even doing here. We came as Jews to the Jewish state, but people don't know what our story is at all. They don't know us."

These painful words are uttered by young members of the Bnei Manasha community in Nof HaGalil, one of 15 communities of immigrants from northern India scattered throughout the country.

The terrible tragedy that struck the community with the terrible murder of the boy Yoel Langhal in Kiryat Shmona, a few months after he immigrated to Israel with excitement, leads the members of this modest community to reveal the painful difficulties of absorption in the country they have been waiting to be a part of, and they hope that this terrible situation may be a sign of a needed change .

It happened on Thursday night before Sukkot.

Langhal, an 18-year-old yeshiva student who immigrated to Israel less than a year ago, went to meet his partner and friends in Kiryat Shmona.

They were waiting for the pizza they ordered, when a group of young boys started harassing them.

The murder - an outcry regarding the treatment of the members of the community.

The late Yoel Langhel, photo: Ancho Josh, Gini

Yoel's father describes what happened there, as his late son's friends told him: "They sat down to eat pizza and boys started cursing at them and then attacked them. They broke his teeth. The police came to check what happened. The attacker ran away, and the friend asked the police to catch the attackers. But the policemen who arrived said everything was fine and left the scene. In the meantime, the attacker invited his friends, who came with helmets and irons to fight with them. Then the disaster happened. They murdered Yoel. His friend tried to save him, until the ambulance arrived."

Everyone feels that this horrible murder could have been prevented.

Joel was murdered only because of his appearance, his origin.

According to his friends, after they complained to the police about the first attack, the uniformed men joked with the attackers and left the scene.

Following the incident, the station commander was removed from his position, but the hard feelings do not let up in Yoel's environment.

For them, this is a rallying cry regarding the treatment of the entire Bnei Manasseh community.

Everyone should hear their story, they say, their love for the land and their attachment to it for thousands of years should be recognized by everyone, and the humiliating treatment they receive from the environment must stop.

Too easy a target

In Nof HaGilil, the northern city where the Langhal family lives, there is the largest Bnei Menasha community in Israel - 300 families, about 1,250 citizens.

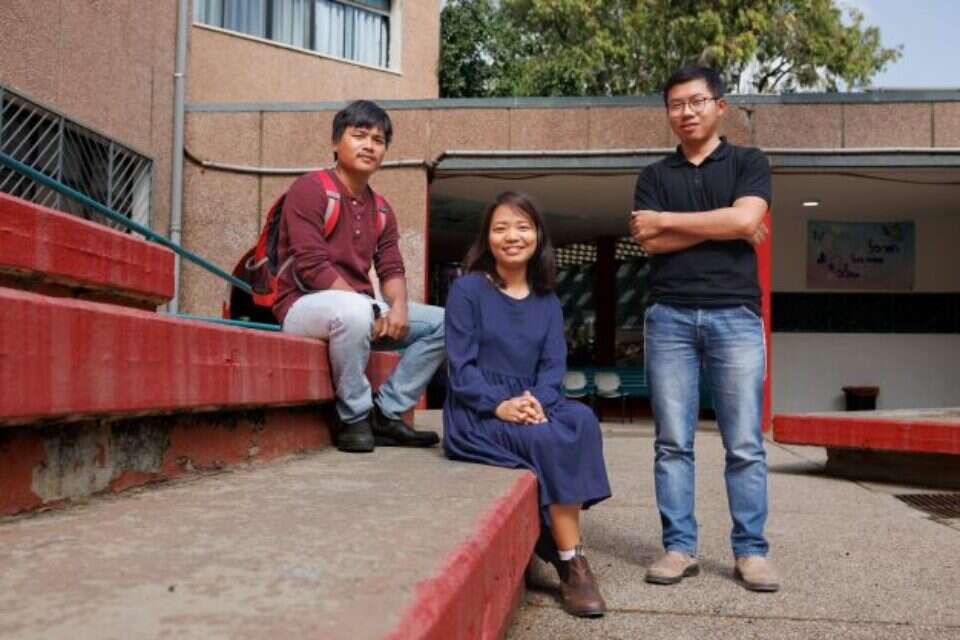

In the local studio class I meet three young people from the community who want to make their voice heard, the voice of the entire community.

Harel Flatuel, 28 years old, works as a manager at Klalit Health Fund.

He immigrated to Israel in 2014 with the first group that arrived in the city and began studying at a kollel until he enlisted in the army.

"We are very connected with the religious residents," he says.

"Everyone knows us, we study with them, we pray with them. But apart from the religious, they don't know us. On Shabbat, when we walk around the city, they constantly shout at us, call us names. Up until now, we got along - we suffered, but we got along. Now it's time to tell how they treat us.

"Every time we walk down the street, we are yelled at by moving vehicles, across the road. Arabs yell at us a lot. Arabs are constantly yelling at us - 'Thai, Chinese,' they start beating us. Every time the police come and they run away. It happens all the time. And what else So? We don't hear anything from the police."

Harel enlisted as a Nahal soldier at the age of 23 and was excited to serve the state. But even there he had to suffer disrespectful treatment. So much so, that they kicked him out of the unit at the end. At first everyone told me 'Thai, Chinese.' It annoys me.

Zvi Hauta: "Since time immemorial, our ancestors celebrated the holidays three times a year, circumcised and sat seven days. Each community has a priest, and for years we continued the custom of sacrifices, and I saw this with my grandparents as well."

"They ask me if I eat cats. Never. I'm Jewish, I wear a kippah, so what don't they understand? They've lived in Israel all their lives, they know what a kippah is. Why don't they still understand? Why, because I have slanted eyes? So We had a department meeting and I told my commander that I wanted to say a few words. I explained to everyone about myself and the community, and the commanders also explained to everyone. If there is laughter after that, that's fine, but let them get to know me first, so that they understand who I am."

Shimshon Panai, 30 years old, immigrated to Israel about five years ago.

He works as an educational mediator in the Nof HaGalil municipality and studies special education.

After immigrating to Israel, he began studying at the Hesder Yeshiva in Nof HaGalil.

In the yeshiva he felt a lot of love, even when he had difficulty with the language in the first year.

"But some people don't like us because we look different," he says, "we are not the stereotype of Israelis, so they talk about us all kinds of nonsense. They ask strange questions that are not acceptable to ask - 'What, are you Chinese?', 'Why are you enlisting in the first place?' ?', 'Are you really Jewish? I don't believe you'.

"In the Galilee landscape, especially here in the city, the Israelis are very accepting of us. But the Arabs here in the city don't accept us at all. They really hate us. You can't walk down the street at night without shouting that we are Chinese and that we have to go back to where we came from. It happens here every night, and it It doesn't happen to other communities here."

Moti Yogev: "Let them be brought down. They were sent to work as cleaners, without sensing the high intelligence they have, without giving them the chance. They yearn to return to the State of Israel in all respects, to Torah life and the army."

Sitting next to him is Ruth Hanamata, 24 years old, who works as a mediator for the community.

She also came up about five years ago.

She completed the conversion process and began studying at the madrassa in Ma'alot and began national service in the process.

"The most difficult thing was the language, but during the service I was able to speak with the children. Before that I was unable to speak at all, and thanks to the children and the service I learned to speak."

She has also gotten used to being asked if she is Thai or Chinese and what she is doing here.

"It hurts that we are not understood. People don't even know what our story is, they don't know us."

What, in your opinion, needs to happen in the country for you to be recognized?

Shimon: "People still don't understand what we went through. In my opinion, we must start teaching our history in schools. If they start teaching at a young age, the young people and boys will know our story, understand who we are."

Harel: "We need to establish a program that will run in schools and tell the story of the community. People now see the news, hear about the disaster, but after that they won't care about us."

Shimon: "People don't believe that something like this can happen. I certainly believe that it happened. Everyone who lives here in Israel experiences racism, there is no one who doesn't. In India we were the minorities. We came to Israel to be safe. We came to be part of the majority, to be part of the Jewish people." .

Ruth: "In India they would laugh at us for wanting to immigrate to Israel."

Harel: "There was anti-Semitism in India. We have to go to the country of our people, to realize our dream, to live with the Jews. So we came all the way here and they don't accept us? Everything we thought is shattered, and this is not perceived because everyone here in the country is a new immigrant, so how does this attitude happen? "

Harel: "You should know - Menashes are very shy people. In the community no one talks to a person they don't know. I don't go to a fight with someone for nothing. We are very quiet. Even when we work in a factory, people won't ask for anything. We are really shy, Even in the army. And in Israel, everyone knows, you have to shout. The first thing you do when you're in the office is to shout, that's how it is here. We don't do that. We sit on the sidelines, listen and wait. That's our nature."

Samson: "This racism will not end until the Messiah comes. It was once, it is happening now and it will be in the future as well. It exists all over the world, it cannot be ignored. What can be done is to build something on top of it and use it as a tool. Take away all the suffering What we passed as an opportunity to rise from this and rise from this. There will be knowledge so that what happened with Yoel will not be in vain and that good things will come out of it, that we will all learn from it and have unity in the end."

Pious preservation of tradition

The story of the Bnei Menasha community is a story of tradition, faith and brotherhood.

A community that maintained its Jewish character for thousands of years, and never gave up the dream of returning to its beloved and distant land.

The ancient tradition was passed down from generation to generation, until the dream came true.

To hear about this unique story, I meet with Dr. Zvi Hauta, director of the immigration and absorption of Bnei Menashe and the absorption center on behalf of the Shavei Israel organization.

Zvi is one of the first immigrants.

22 years ago he settled in Kiryat Arba, where he currently lives with his wife and five children.

His eldest son was two years old when they immigrated, and the other four children were born here.

Recently, his two eldest sons completed regular military service in the paratroopers, and one of them received a Presidential Distinguished Service Medal last year.

"It hurts that they don't understand us, people don't understand what our story is."

The children of the Bnei HaMansha community in Nof HaGalil, this week, photo: Ancho Josh, Gini

Zvi lives the needs of the community on a daily basis, and their historical story emerges from his mouth with passion and sensitivity.

"According to tradition, we were in exile for more than 2,700 years. Our ancestors told us that the king of Assyria kidnapped us to Assyria, from there to Afghanistan, and from there to China. Some stayed in China and some took a long route and reached Myanmar-Burma, and from there we entered northeastern India. Our ancestors did not call themselves Jews or Israelis, but sons of Manasseh. This is our tradition."

The Manasseh settled in northern India, and two other Jewish communities also existed in Mumbai and Cochin.

The mitzvot of the Torah were a significant part of community life.

"Since time immemorial, our ancestors celebrated the holidays at least three times a year, circumcised on the eighth day and sat for seven after burying the dead. Every community has a priest, but the relationship to him is not spiritual, but like a doctor. If something happened in the community or family - they turn to the priest He says - one should make an individual sacrifice or a public sacrifice. Our ancestors continued with the sacrifices for many years. Even as a child I saw my grandparents who kept the tradition of sacrifices.

Harel Flatuel: "The Menashes are very shy people. In the community no one speaks to a person they don't know. I don't just go to a fight with someone. We are very quiet, even in the army. And in Israel, everyone knows, you have to shout."

"We also have a song about the splitting of the Red Sea in our language - Kuki - and we pray to God, to one God, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, the God of Jacob, this is part of the prayer.

We have longing songs for Zion, ancient songs for Jerusalem.

For thousands of years there was no assimilation, you only marry members of the community.

Thanks to this, everyone knows that we are Jews."

The tradition that was passed down from generation to generation for more than two thousand years began to erode only in 1890, when British missionaries arrived in the region and began to convince the community members to accept the New Testament as their Judaism.

Most of the congregation followed the missionaries, except for a minority of conservatives who refused to change their customs.

"The British missionaries started to establish educational institutions," says Zvi, "those who sent their children received free education and food. Thus, within 50-100 years, significant assimilation began. Before the British came, this did not exist at all. They gave us the New Testament and told us to translate from English to Cuckoo. Because it resembled the customs of our ancestors, almost all of them became Christians. Only the most conservative of us remained, keeping the holy tradition. My grandfather was the chief of the neighborhood, and he did not agree that the British should establish a Christian church. But with the generations it became more difficult. The conservatives became the minority among minorities, still continuing this tradition."

After the establishment of the State of Israel, the conservative representatives began to contact representatives in Israel, among others with Golda Meir.

But they did not get an answer.

Salvation came from Rabbi Eliyahu Avichail, who began dedicating his life to locating the ten exiled tribes.

In 1964 he came to visit the community and since then worked hard to immigrate its members to Israel, until the first immigration to Israel in 1981. A few more years passed before a significant immigration could take place, thanks in large part to the establishment of the Shabi Israel organization, by a philanthropist named Michael Freund who saw this as a mission.

Unequal absorption

Raising the community was a complex and complicated process.

In 2004, the Chief Rabbi at the time, Rabbi Shlomo Moshe Amar, sent a delegation to investigate the origin of the community.

Finally he decided that this is a community that is the seed of Israel, but because of the fear of assimilation a full conversion is needed.

As far as the community was concerned, there was no objection, and they were happy about the renewed connection to the Jewish people, which they had been striving for for generations.

The problem was when the Indian government refused to authorize the conversion of 300 people on its soil.

Hauta: "Following the ban, we stopped, but if not for that, everyone would have converted and according to the Law of Return they could have returned home. But the Law of Return does not apply to us because it only checks up to a third generation back, and we have a tradition that goes back several dozen generations. So 232 families They converted according to the Law of Return, and Shabi Israel helped bring them up."

"If he had sacrificed his life for the country in military service - we would understand."

Yoel's parents, photo: Ancho Josh, Gini

The Shebi Israel organization operates a sub-studio in the Galilee landscape, and the members of the community are spread over 15 communities throughout the country, many of them in the north - Kiryat Shmona, Tiberias, Beit Shean, Migdal Hamek, Acre, Ma'alot and more.

In the studio classroom where I met Hauta and the three young men, I also found former MK Moti Yogev, sitting and talking with parents and children who are members of the community.

Yogev currently serves as a projector for the city of Nof HaGalil, and is deeply connected to the community of Bnei Manasha.

"These are amazing people, intelligent people with a special emotional intelligence, but in many places they don't know how to treat them. We suppressed them. They sent them to work as cleaners, without feeling the high intelligence they have, without giving them the chance. They yearn to return to the State of Israel in every way, to return to the Torah and to the army and state life."

Yogev testifies that there is a problem in the absorption process of the community in Israel.

"The conditions of their absorption must be compared to the conditions of the Ethiopian immigrants. The Bnei Menasha come from a mentality very different from that of an advanced country, and they were allotted only five months of language study. Ethiopian immigrants are in absorption centers for between one and three years. The Bnei Menasha immigrants only have a few months of absorption basket , like accepting immigrants from France. This is not enough. That way the immigrant cannot realize his potential. Once they have better Hebrew, there will be more academics and they will be able to work in more significant jobs."

Yogev accompanied the local youth after the murder and heard their pain.

"It was important to us that these feelings do not lead to severe anger. We are looking to see how to make flesh out of the crisis, in the words of the late Emmanuel Moreno.

We are busy creating programs to uplift Yoel's soul - training courses, a program for youth in the Negev during Hanukkah, including Torah study in his memory."

For him, this is just the beginning, and he has other big dreams for the future of the community: "We are building the first Bnei Akiva branch of the Bnei Menashe in the Galilee landscape. The communal is from the Bnei Mansheh community, as well as the instructors. Informal education is just as important as formal education. Bnei Menashe is a community of people Amazing, humble, humble, responsible, with a strong desire to return to the People of Israel and the Land of Israel, so much so that in their tradition they are supposed to return to their original inheritance in the tribe of Menashe. We want to establish a settlement for them in the Golan, where the tribe of Menashe lived. This is a thought that I began to consider this year. We were In an initial meeting with the head of the settlement council, and I hope it will have an executive channel."

In the home of the late Yoel Langhal, his bereaved parents, Gideon and Batsheva, are sitting. Next to them is a little baby girl born in June, wrapped tightly in a blanket. Gideon's parents are sitting on an armchair opposite. During the conversation with them, Yoel's two little brothers and a sister come in quietly and happily, returning from school. The family immigrated to Israel only six months ago. They still don't speak Hebrew, and answer my questions with a smile after the representative of the absorption center, Shimon Ha'Okip, translates for us.

"Let there be free love"

"It was our dream, to immigrate to the Land of Israel and live happily," says the father in a weak voice.

"The sadness now is indescribable, it is very difficult. The time has passed, we cannot forget. He had a desire to study Torah, do sports, he was attentive and helped a lot at home. He helped my mother a lot with the daughter who was born. He said - 'If I immigrate to Israel , I'm learning Torah, enlisting in the army to be a fighter'. But his dream will no longer come true, he didn't enlist."

Gideon Langhal: "Yoel wanted to build a sukkah together. When we finished, he told me that he wanted to visit Kiryat Shmona with close family and his girlfriend, and bring the family here for sukkah. Until now we are waiting to celebrate with him."

The last thing the father and son did together was build a sukkah.

"He wanted to fulfill the mitzvah of building a sukkah and sitting in it. We bought all the parts of the sukkah and started building. When we finished, Yoel told me that he wanted to visit close family in Kiryat Shmona and his girlfriend. He said he would return after Shabbat and that he wanted to bring the family here to make sukkah together. We are still waiting to celebrate Sukkot with him. That won't happen either."

About life in India and immigrating to Israel, Gideon says: "In India we lived a good life. We had a car, we grew our own vegetables. We lived in the village of Patlin, in Manipur. Although all life there was good, our dream was to immigrate to our land, the land of all the Jewish people, because we Men of the Menashe tribe and this is our dream - to live in the Jewish state. If my son had been killed to defend Israel, in the war, in the army, we would have been able to understand it. But he was murdered by a Jew, here in the Jewish state. It was not understood."

When I ask him, before we say goodbye, how he would like Yoel to be commemorated, he replies: "By studying the Torah, that a Torah book be written for the uplifting of his soul. To observe mitzvot, as many mitzvot as possible. Let there be free love between everyone. When there is unity with our Jewish brothers, such a thing will not will happen again."

were we wrong

We will fix it!

If you found an error in the article, we would appreciate it if you shared it with us