Editor's Note:

Don't miss the special "World's Untold Stories: The Brain Collectors" this November 12-13 on CNN International.

(CNN) --

For years, it had been hinted at.

It was rumored, stories were exchanged.

It wasn't a secret, but it wasn't openly talked about either, which made for a legend almost too unbelievable to believe.

However, those who knew the truth wanted it to be known.

Tell everyone our story, they said, about the brains in the cellar.

a family secret

As a child, Lise Søgaard also remembers the whispers, although these were different: the kind of family secret, kept quiet because it was too painful to speak out loud.

Søgaard didn't know much about it, except that these whispers centered on a family member who seemed to exist only in a photograph on the wall of his grandparents' house in Denmark.

advertising

The girl in the photo was called Kirsten.

She was the younger sister of Søgaard's grandmother Inger.

"I remember looking at this little girl and thinking, 'Who is she?'

'What happened?'".

Sogaard said.

"But also this feeling that there was a little horror story in there."

Upon reaching adulthood, Søgaard continued to wonder.

One day in 2020, she went to visit her grandmother, now in her 90s and living in a nursing home in Haderslev, Denmark.

After all that time, she finally asked about Kirsten.

Almost as if Inger had been expecting the question, the floodgates opened, and a story Søgaard hadn't expected came out.

Top left: Kirsten (top center) and her sister Inger (bottom left) on a family outing with their aunt, uncle and cousin.

Bottom left: The Abildtrup family in the early 1930s. Kirsten, center left, holding hands with her mother, was the youngest of seven children.

On the right: the photo of Kirsten that she hung on the wall and that first caught Søgaard's attention when she was a child.

Credit: Lise Sogaard

Kirsten Abildtrup was born on May 24, 1927, the youngest of five children and her sister Inger.

As a child, Inger recalls that Kirsten was quiet and intelligent, and that the two sisters had a very close relationship.

Then, when Kirsten was about 14 years old, something started to change.

Kirsten experienced prolonged outbursts and crying spells.

Inger would ask her mother if it was her fault, and she often felt that way because the two girls were very close.

"At Christmas, they were supposed to visit relatives," Søgaard said, "but my great-grandmother and father stayed home and sent all their children except Kirsten."

When they returned from that family visit, Søgaard said, Kirsten had disappeared.

It was the first of many hospitalizations, and the beginning of a long and painful journey that would end in Kirsten's death.

The diagnosis: schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia could be eight different diseases

The brain collectors

Kirsten was first hospitalized towards the end of World War II, when Denmark and the rest of Europe were finally on the brink of peace.

Like so many other places, Denmark also struggled with mental illness.

Psychiatric institutions had been built all over the country to care for patients.

Doctors prepare a patient for electroshock therapy at the Augustenborg Psychiatric Hospital in Denmark, 1943. Credit: AE Andersen/Ritzau Scanpix/AP

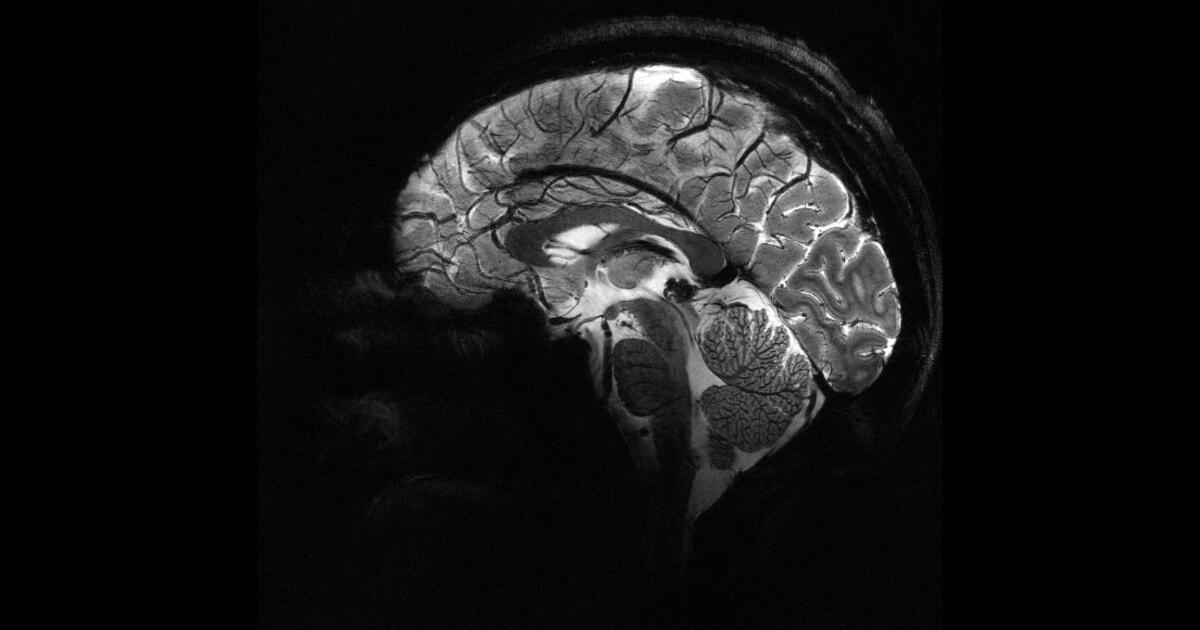

But understanding of what was going on in the brain was limited.

The same year peace came to Denmark's doorstep, two doctors working in the country had an idea.

When these patients died in psychiatric hospitals, autopsies were routinely performed.

What if, these doctors thought, the brains were removed...and preserved?

Thomas Erslev, a historian of medical science and research adviser at Aarhus University, estimates that half of the psychiatric patients in Denmark who died between 1945 and 1982 contributed their brains, unknowingly and without their consent.

They ended up in what became known as the Institute of Cerebral Pathology, linked to the Risskov Psychiatric Hospital in Aarhus, Denmark.

Doctors Erik Stromgren and Larus Einarson were the creators of the collection.

After about five years, Erslev said, pathologist Knud Aage Lorentzen took over the institute, spending the next three decades building the collection.

Dr. Larus Einarson, shown here lecturing, was one of the co-founders of the brain collection at the Institute of Brain Pathology.

Credit: Arne Sell/Aarhus University

The final count would amount to 9,479 human brains, which is believed to be the largest collection of its kind anywhere in the world.

Moving almost 10,000 brains

In 2018, pathologist Dr. Martin Wirenfeldt Nielsen received a call.

The Brain Collection, as it would come to be known, was on the move.

Lack of funding meant he could no longer stay in Aarhus, but the University of Southern Denmark, in the city of Odense, had offered to take over.

Would Wirenfeldt Nielsen be interested in supervising it?

Pathologist Dr. Martin Wirenfeldt Nielsen now oversees the brain collection, housed in Odense, Denmark.

Credit: Samantha Bresnahan/CNN

“I had only marginally heard of it,” recalls Wirenfeldt Nielsen.

“But the first time I found out about its magnitude was when they decided to move it here… (because) how can you move almost 10,000 brains?” she said.

The yellow-green plastic buckets containing each brain, preserved in formaldehyde, were placed in new, sturdier white buckets for shipping, and hand-labeled with a number in black marker.

And so the brains, more or less (no one knows where No. 1 is, for example), made their way to their new home in a large basement room on the university campus.

"The room was not ready when it was moved here," explains Wirenfeldt Nielsen.

"The whole collection was there, buckets on top of each other, in the middle of the floor. And that's when I saw it for the first time... It was like, okay, this is something I've never seen before."

An ethical reckoning

Finally, the almost 10,000 buckets were placed on mobile shelves, where they remain today, waiting, representing lives, and a series of psychiatric disorders.

There are about 5,500 brains with dementia;

1,400 with schizophrenia;

400 with bipolar disorder;

300 with depression, and more.

What sets this collection apart from any other in the world is that the brains collected during the first decade are untouched by modern medicines: a kind of time capsule for mental illness in the brain.

"While other brain collections ... (are) maybe specified for neurodegenerative diseases, dementia, tumors or other things like that, here we really have everything," said Wirenfeldt Nielsen.

But it has not been without controversy.

In the 1990s, the Danish public became aware of the existence of the collection, which had lain dormant since the retirement of former director Lorentzen in 1982.

This gave rise to one of the first great ethical debates about science in Denmark.

"There was a back and forth debate, and one of the positions was that we should destroy the collection: bury the brains or dispose of them in some other ethical way," explains Knud Kristensen, director of SIND, the Danish national association for health. from 2009 to 2021, and current member of the Danish Ethics Council.

"The other position was: OK, we've already done harm once. So the least we can do for these patients and their families is make sure the brains are used for research."

The history of the brain collection

1945

The Institute of Brain Pathology is founded, linked to the Risskov Psychiatric Hospital in Aarhus, Denmark

Risskov Hospital, photographed in the early 1900s.

Credit: Ovartaci Museum

1945-1982

About 9,500 brains are harvested without permission from deceased psychiatric patients across Denmark

The brains were collected and shipped from Danish hospitals, including the Rigshospitalet (pictured), in Copenhagen.

Credit: Jesper Vaczy/Medical Museum

1982

The head of the brain collection, Knud Aage Lorentzen, retires.

Nobody takes his place and the collection remains intact in a basement.

The brains, shown here in their original yellow packaging, would remain virtually intact for more than 20 years.

Credit: Hanne Engelstoft

1987

Danish Ethics Council established

The Ethics Council is an independent group formed to advise the Danish Parliament (this photo, in 2016) on ethical matters.

Credit: olli0815/iStock/Getty Images

1991

After the Ethics Council said that brains can be used with certain restrictions, the Danish National Psychiatric Health Association (SIND) requires that brains be buried, sparking one of the first debates Important ethical scientists in Denmark

Some pieces of brain material are preserved in paraffin wax.

Credit: Hanne Engelstoft

2005

Danish scientist Karl-Anton Dorph-Petersen takes over the daily maintenance of the collection in Aarhus

Karl-Anton Dorph-Petersen helped revive and preserve the collection in the mid-2000s.

Credit: Hanne Engelstoft

2006

The Ethics Council goes against political and religious demands by ruling that it is ethically correct to use the brains of deceased psychiatric patients for research without obtaining the consent of the relatives.

This time, the SIND agrees

The collection includes patient records and tissues preserved on slides, such as these.

Credit: Hanne Engelstoft

2017-2018

A lack of funding threatens the brains, and the collection is saved by moving it to Odense, where Dr. Martin Wirenfeldt Nielsen takes over.

The brains were placed in new white bins for shipment to Odense, where they remain safely stored on rolling racks.

Credit: Samantha Bresnahan/CNN

Source: Thomas Erslev, historian of medical science

Graphic: Woojin Lee, CNN

After years of intense debate, the SIND changed its position.

"All of a sudden, they became strong advocates for preserving brains," Erslev said, "actually saying this could be a very valuable resource, not just for scientists, but for psychiatric patients, because it could be beneficial for therapeutics." later".

"For (SIND)," Kristensen explained, "it was important where it was located and to make sure that there would be some sort of control over future use of the collection."

When it was moved to Odense in 2018, the ethical debate was largely resolved, and Wirenfeldt Nielsen became caretaker of the collection.

A few years later, he would receive a message from Søgaard.

Was it possible, he asked her, that he had in there a brain belonging to a woman named Kirsten?

Looking for Kirsten

In searching for what happened to his great-aunt Kirsten, Søgaard realized that there were clues all around him.

But piecing together exactly what had happened to his grandmother's sister was slow, full of dead ends and setbacks.

However, she was captivated and began officially reporting on her trip for the Kristeligt Dagblad, the Copenhagen newspaper where she worked, eventually releasing a series of articles.

At one point, Søgaard decided to focus on a single word his grandmother had told him, the name of a psychiatric hospital: Oringe.

"I grabbed my computer and looked up 'Oringe patient diaries,'" he said.

After making a request through the national archives, "I got an email that said, 'Okay, we found something for you, come take a look if you want.' ... I felt that emotion ... like it was there outside".

Journalist Lise Søgaard set out to find out what had happened to her grandmother's little sister, Kirsten, a journey that would take her to places she never imagined.

She shared that experience with CNN's Dr. Sanjay Gupta at her home outside Copenhagen in April 2022. Credit: Cameron Bauer and Samantha Bresnahan/CNN

That excitement was short lived.

In the national archives, an almost empty file was placed in front of him.

It wasn't much to go on, but it confirmed Kirsten's diagnosis of schizophrenia.

With no other solid lead, Søgaard wondered where to go next.

Then, almost in passing, as they looked at old family photos together, her mother said something she had never heard before.

"He said, 'You know, they may have kept his brain,' and I was like, 'What?!' Søgaard told CNN's Dr. Sanjay Gupta at his home outside Copenhagen. "And he told me what he knew about the collection of brains".

living with schizophrenia

At 95, Søgaard's grandmother Inger can still clearly imagine visiting her little sister Kirsten in hospital, after the symptoms she started experiencing at age 14 continued to progress.

On one of her visits, Inger recalled, "(Kirsten) was lying there, completely listless. She couldn't talk to us. ... Another day we went to visit her and she was no longer in her room. They told us she had thrown a glass at her." a nurse and that they had sent her to the basement, to a room where (they held her) with belts. We were not allowed to go in, but I saw her through a hole in the door; she was lying there, tied up."

One of the floors of the Oringe psychiatric hospital is now a museum displaying medical treatments and patient rooms, like this one.

Credit: Samantha Bresnahan/CNN

Inger felt confused and scared, she said, because it could have been anyone, including her, who could "get sick."

At Sankt Hans, one of Denmark's oldest and largest psychiatric hospitals, Dr. Thomas Werge walks the same grounds he walked as a child, when his own grandmother was hospitalized there.

He now directs the Institute for Biological Psychiatry, where he and his team study the biological causes that contribute to psychiatric disorders.

A 2012 study found that about 40% of Danish women and 30% of Danish men had received treatment for a mental disorder in their lifetime, although Werge estimated that figure would be "almost certainly" higher if perform the same study today.

(By comparison, that same year, less than 15% of American adults received mental health services.)

Among the other Nordic countries, including Sweden and Norway, Werge said the figures would be comparable to Denmark, as there are "similar [universal] healthcare systems and admission standards."

"Mental (health) disorders are everywhere," he added.

"We just don't recognize it when we walk among people. Not everyone shows their pain to the outside."

In the case of schizophrenia, there are no blood tests or biomarkers to indicate its presence;

instead, doctors should rely solely on clinical examination.

Schizophrenia presents in what the World Health Organization (WHO) calls "significant alterations in the way of perceiving reality", causing psychoses that can include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized behavior or thoughts and extreme agitation.

According to the WHO, approximately one in 300 people worldwide suffers from schizophrenia, but less than a third of them receive specialized mental health care.

Since the mid-1950s, the standard treatment has been antipsychotic drugs, which typically work by manipulating levels of dopamine—the brain's reward system.

But, according to Werge, this may come at a cost.

"Schizophrenia and psychosis are related to creativity," he says.

"So when you're trying to inhibit psychosis, you're also inhibiting creativity. So there's a price to be medicated... What causes all these problems for humans is also what makes us human in a good way."

Dose of Synthetic 'Magic Mushroom' Helped Ease Severe Depression: Study

Brain #738

Although there have not been many significant scientific advances in understanding the disease, researchers have confirmed that genetics and heredity play a role.

According to Werge, the estimate of heredity reaches 80%, the same as height.

"It's not a surprise to people that if you have very tall parents ... there's a lot of genetics to it," she said.

"The genetic component is just as big in most mental disorders, in fact."

These inherited genetic factors come from the parents, he added, or can arise in a child even if the parents do not carry the gene.

Søgaard, who has two young children, said the genetic connection was not a motivating factor in her quest to find out what happened to Kirsten, but she has thought about what it means for her and her family.

Cuando las familias se ponen en contacto con posibles parientes en la colección de cerebros, "es un dilema ético que debemos tener en cuenta", dijo Wirenfeldt Nielsen. En el caso de Søgaard, recibió la aprobación para que los Archivos Nacionales daneses revisaran el conjunto de libros negros que contienen los nombres de todas las personas cuyo cerebro está en la colección.

En la lista estaba el nombre de Kirsten.

"Recibí un correo electrónico [de los Archivos Nacionales], y escanearon la página donde estaba el nombre de Kirsten, y su fecha de nacimiento, y el día en que recibieron el cerebro. Y en la columna de la izquierda había un número", recordó Søgaard. "El número 738". Inmediatamente escribió un correo electrónico a Wirenfeldt Nielsen, preguntando si ese número correspondía al balde con el cerebro de Kirsten.

"Le dije: 'Sí, es ese'", recordó Wirenfeldt Nielsen. Pero también dijo que no podía estar seguro de que el balde estuviera allí porque faltaban algunos por razones desconocidas. Se aventuró a bajar al almacén del sótano para comprobarlo.

En uno de los estantes estaba el balde nº 738.

El cerebro de Kirsten

El balde 738, el cerebro de Kirsten, está en una estantería entre el resto de la colección de cerebros en el sótano de la Universidad del Sur de Dinamarca en Odense. Crédito: Samantha Bresnahan/CNN

Cuando Søgaard lo vio por primera vez, sintió un impulso de abrazar el balde.

"Había aprendido mucho sobre Kirsten", dijo. "Siento una especie de conexión... (y) conozco el dolor que sentía, y sé por lo que pasó".

El "corte blanco"

Lo que vivió Kirsten fue otro golpe extraordinario en esta increíble historia, y en la larga historia de la atención psiquiátrica en Dinamarca.

Como parte de su tratamiento, Kirsten recibió lo que se conoce comúnmente en Dinamarca como "el corte blanco".

En términos médicos: una lobotomía.

Este procedimiento forma parte de la historia psiquiátrica del país. Durante el tiempo que duró la colección de cerebros, desde los años cuarenta hasta principios de los ochenta, se dice que Dinamarca hizo más lobotomías per cápita que cualquier otro país del mundo.

"Es un tratamiento muy pobre, porque se destruye una gran parte del cerebro", dijo Wirenfeldt Nielsen. "Y es muy arriesgado, porque puedes matar al paciente, básicamente, pero no tenían otra cosa que hacer".

Las opciones de tratamiento eran limitadas, y en muchos sentidos extremas. Las convulsiones se inducían colocando electrodos a ambos lados de la cabeza; la terapia de choque con insulina suponía administrar a los pacientes grandes dosis de insulina, lo que reducía el nivel de azúcar en la sangre y provocaba un estado comatoso; y la lobotomía, ya fuera transorbital, utilizando un instrumento parecido a un pico que se insertaba a través de la parte posterior del ojo hasta el lóbulo frontal, o prefrontal.

La lobotomía prefrontal fue iniciada por un neurólogo portugués, Antonio Egas Moniz. Aunque ahora se considera una barbaridad, ganó el Premio Nobel por este procedimiento en 1949.

Se inserta una herramienta en el lóbulo frontal, raspando tramos de materia blanca, lo que explica el apelativo de "corte blanco". "Las reacciones emocionales... se localizan, al menos en parte, en el lóbulo frontal", explica Wirenfeldt Nielsen, "así que pensaron que cortando (ahí) se podría calmar al paciente".

Izquierda: el neurólogo portugués Antonio Egas Moniz recibió el Premio Nobel en 1949 por ser el pionero de la lobotomía prefrontal. Arriba a la derecha: las lobotomías se convirtieron en una opción de tratamiento muy popular desde los años 30 hasta principios de los 50. Aquí, un cirujano perfora el cráneo de un paciente en un hospital de Inglaterra, en 1946. Abajo a la derecha: al cortar segmentos de materia cerebral en el lóbulo frontal, se creía que la lobotomía podía tratar los síntomas de la enfermedad mental. Crédito: Boyer/Roger Viollet/Getty Images, Kurt Hutton/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images, Ilustración: Prof. E.A.V. Busch

En el caso de Kirsten, Inger dijo que había destellos de "la antigua Kirsten" antes de que se hiciera la lobotomía, pero que después de eso, se había ido. En 1951, un año después de su lobotomía, murió.

Solo tenía 24 años.

Una promesa para el futuro

En una mesa metálica situada en un pequeño edificio independiente en los terrenos del hospital psiquiátrico de Oringe, se extrajo el cerebro de Kirsten, se introdujo en un pequeño balde de plástico, se colocó en una caja de madera y se envió, por correo ordinario, al Instituto de Patología Cerebral de Risskov, para que se uniera a la colección de cerebros.

Søgaard vio la mesa de metal, en la que todavía hay un bloque de madera blanca en un extremo, donde se colocaban las cabezas, y sobre el que todavía se ven pequeñas marcas. Aquí es donde se abrían los cráneos.

El edificio independiente de Oringe (izquierda) que alberga la sala de autopsias donde se extrajo el cerebro de Kirsten en 1951 sigue en pie hoy en día, e incluye las cajas de madera (derecha) que se utilizaron en su día para enviar los cerebros a Risskov. Crédito: Samantha Bresnahan/CNN

A pesar de los recordatorios explícitos, al informar sobre esta historia tanto para ella como para el periódico, "era importante (para mí) no escribir una historia que fuera una historia de terror", dijo, añadiendo que era fácil mirar atrás y decir: "¿Cómo pudieron hacer eso?"

"No creo que los médicos quisieran hacer el mal. Creo que en realidad querían hacer el bien. ... Creo que lo más ético que se puede hacer es asegurarse de que se sabe exactamente lo que se puede hacer con estos cerebros. Y eso es lo que están haciendo ahora. Intentan averiguar cómo pueden ayudarnos".

A lo largo de los años se han realizado estudios con la colección, incluido el descubrimiento en 1970 de lo que ahora se conoce como demencia familiar danesa, y se está llevando a cabo un nuevo estudio, centrado en el ARNm de los cerebros, a cargo de la investigadora danesa Betina Elfving.

For the most part, brains represent enormous untapped potential.

Bucket 738 has already accomplished something extraordinary, though, thanks in no small part to Søgaard herself.

She worked to break the cycle of stigmatization surrounding mental health disorders by sharing her most personal and intimate family details with the world.

"(My grandmother) expressed her gratitude," Søgaard said.

"She also said, 'I feel like I'm closer to my sister now.'"

human brainDenmarkMental Health