In the mythical Yellowstone National Park (United States), wolves infected with

Toxoplasma gondii

are up to 46 times more likely to be the leader of the pack than healthy ones.

In addition, those affected by toxoplasmosis caused by this parasite tend to engage in more risky behaviors.

These patterns, observed over the last 25 years, would be related to the greater or lesser presence of the other great predator in the national park, the puma.

Both animals share territory and where the density of pumas is higher, so is the infection by

T. gondii

among the canids

This parasitic protozoan, feared by all cat owners, needs cats to complete its life cycle.

With the help of evolution, it has managed to influence the behavior of large predators such as wolves.

T. gondii

it can infect any warm-blooded species.

Once it sneaks into the body, it develops cysts in various parts of the body, especially muscles and brain.

Although it could affect up to a third of humans, it is only dangerous in babies born to infected mothers and people with weakened immune systems.

In its life cycle, it goes through several phases of development, beginning in a feline, followed by an external phase that begins in its urine and feces, requiring intermediate hosts before completing its reproduction again in another feline.

This life cycle has caused a strange relationship between infected rodents and cats.

Several studies have found that mice or rats with toxoplasmosis are attracted to the smell of cat urine, which exposes them to being hunted and thus

T gondii

reaches its final host.

A similar manipulation would be taking place with the great predator of Yellowstone National Park.

Every year, the park's conservators capture a dozen wolves to do a complete checkup.

They have data for decades.

Until 1999 all serological samples were negative for

T. gondii

, but the following year the first cases appeared.

In 2020, the latest year for which data is available, more than 36% of the nearly 250 wolves tested had the parasite.

The prevalence of toxoplasmosis has also been increasing among pumas, with more than half affected out of the 62 studied.

The causes of this increase are not clear, but, according to the experts, they could be related to the success of the recovery of both species within the park, rather than the introduction of the parasite by other vectors, such as the domestic cat.

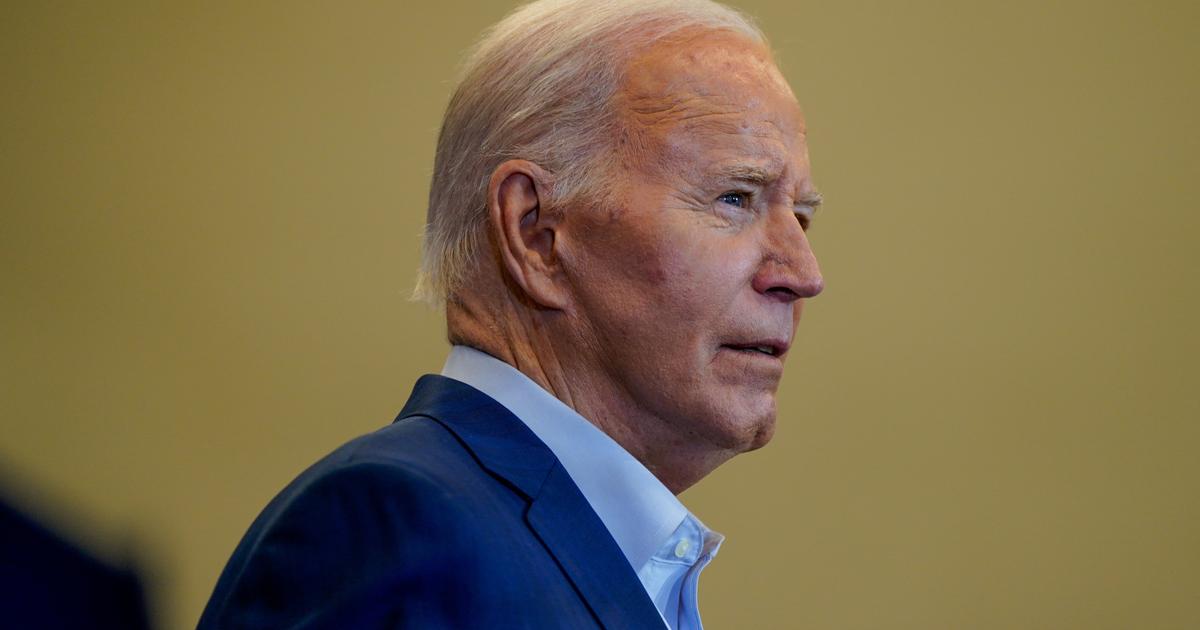

Aerial photo taken by the US National Park Service in Yellowstone in 2019. AP

These numbers led park scientists to wonder if, beyond health,

T. gondii

was having an impact on behavior.

With the data accumulated in the last 25 years, they collected cases of risk behaviors and grouped them into three categories.

First, its adaptation to human presence, getting closer and closer to humans and cars.

In addition, they looked at straying from the pack, since, like humans, wolves are social animals and loners have a higher mortality rate.

Lastly, they reviewed the fights for the throne, the disputes over the leadership of the pack.

These canids have a very defined social hierarchy and the position of leader is won by challenging the leader of the pack.

The follow-up results, published in the specialized journal

Communications Biology

, found no relationship between infection by

T. gondii

and closer to humans.

However, they found that for every healthy lone wolf, there were two infected that had strayed from the pack (an affected percentage of 18% vs. 36%, respectively).

Even more intriguing: HIV-positive wolves are much more likely to be the leader of the pack, specifically up to 46 times more than HIV-negative wolves.

These observations fit with a third.

The study authors found that the degree of overlap between the ranges of pumas and wolves appeared to be related to disease incidence.

Thus, while in areas with a low density of cats, the prevalence of toxoplasmosis did not reach 15%, where these large cats abounded, 37% of the canids were infected.

"If wolves were to catch a cougar on the ground, they would likely attack and kill it, that may be one way wolves are becoming infected with toxoplasmosis."

Connor Meyer, researcher at the University of Montana, United States

Connor Meyer, a graduate student at the University of Montana (United States), spent several seasons in Yellowstone investigating this strange trio of wolves, parasites and cougars.

“Wolves don't necessarily avoid pumas.

In direct interactions between the two species, they pose more of a danger to pumas than they do to wolves," Meyer recalls, adding: "If wolves caught a puma on the ground, they would likely attack and kill it, and that may be one way wolves are getting infected with toxoplasmosis.”

Or vice versa, that it is a way by which the parasite manages to reach its final host in the fray and complete its life cycle.

Meyer and her colleagues at the National Park Service who collaborated on the research are concerned about the impact of these risky behaviors on the herd as a whole.

“The pack leaders, it seems the female leader especially, have a lot to say about how, when and where a pack moves through the territory.

So it could be

teaching

uninfected packmates to make riskier decisions," recalls the American scientist.

For now, they have not detected increased mortality from causes related to behavior among those infected with

Toxoplasma gondii

.

What does the parasite gain by

choosing

the leader of the pack?

In rodents, the almost mechanical relationship between infection and approaching cats, the necessary destination for these protozoa, has been seen.

Some studies have observed that infected chimpanzees lose their aversion to leopard urine, an unequivocal sign that one is around and that leopards are their great predator.

Meyer opines along these lines: “This is all speculative, but evolutionarily, if we look back to Pleistocene North America, wolves would be further down the food chain and there would still be American lions [extinct about 8,000 years ago].

If so, we would probably see something similar to what we see in spotted hyenas and African lions, where toxoplasmosis-positive hyena cubs are more likely to approach lions... So,

Hyenas infected by 'T.

gondii' tend to get closer to lions, their great enemy.Zachary M. Laubach

Meyer's reference to hyenas refers to research published last year that led to a fascinating discovery: taking into account all causes of mortality among spotted hyena pups, 100% of the infected dead fell under the jaws. of the lions, compared to 17% of the healthy deceased.

The work, based on three decades of observations of two hundred hyenas from the Masai Mara reserve, found that the offspring affected by the parasite were more reckless, engaging in obviously risky practices, such as not keeping their distance from lions.

Adult hyenas with toxoplasmosis also tempted their luck more, getting closer to their only great enemy.

The result is increased mortality.

Of 33 cases of dead hyenas with a known cause,

those infected were twice as likely to have been killed by the big cats.

Lions don't eat hyenas, but just biting their head opens up the possibility of hyena cysts.

T. gondii

pass to the lion and the parasite can reproduce again.

The ecologist at the University of Colorado in Boulder (United States) Zachary Laubach, who participated in the research with the hyenas, details that "infected cubs had a higher mortality caused by lions than uninfected cubs", although he acknowledges that the size of the sample was relatively small.

Regarding rank, they did not observe a connection between parasite and leadership.

The social hierarchy in both species is very different.

Hyenas inherit the range of their mothers.

Also, the size of the group is very different.

Among wolves, packs number about half a dozen animals, all related.

Among hyenas, clans can be made up of more than 100 adults.

Leaving domestic cats aside, the cases of chimpanzees, wolves and hyenas would explain the survival of the parasite among humans as a legacy of the past.

Today, the parasite appears to be associated with a higher incidence of suicide and aggressiveness, but we are no longer a good intermediate host.

But in the past, as the authors of the wolf study point out, humans were also prey to big cats.

You can follow

MATERIA

on

,

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.