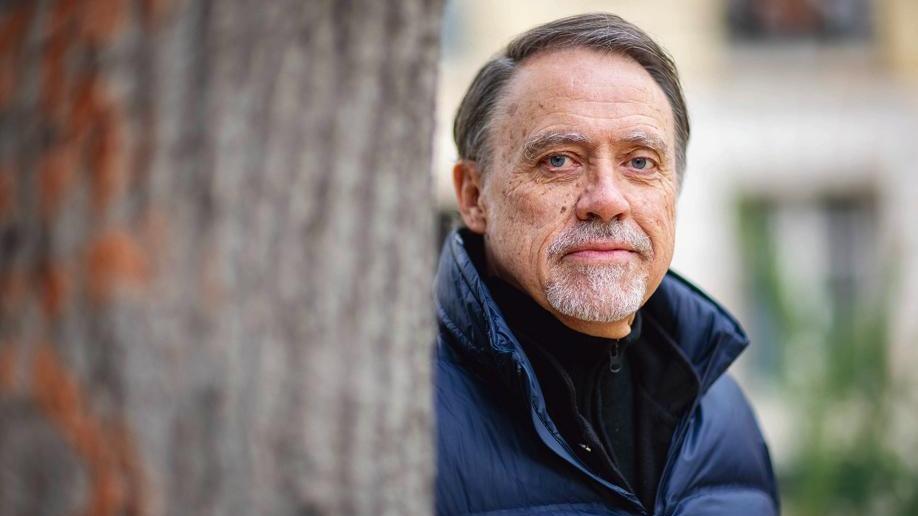

For Professor Joseph Heinrich (Norristown, USA, 54 years old) the classical cultural explanations of anthropology were not effective for understanding the psychological differences between people.

So this anthropologist, chair of the Department of Human Evolutionary Biology at Harvard University, set to work on his second book

The World's Weirdest People: How the West Became Psychologically Quirky and Particularly Prosperous

(Captain Swing).

With this voluminous work he intends to explain how populations differ around the world and why

strange societies

—by its English acronym WEIRD, “western, educated, industrialized, wealthy and democratic”—cannot be used as the global standard by which to look at humanity as a whole.

To explain these differences, the researcher combines the scientific work of his field in evolutionary anthropology, along with psychology, history and economics, always taking into account the strong biological roots of human behavior.

Heinrich applies an interdisciplinary approach to study the origins and evolution of family structures, placing special emphasis on the institution of marriage and religious norms.

The basis from which it starts is the following: these social behaviors throughout the centuries have had a great cumulative impact on human psychology, until making Westerners the strangest people in

the

world.

More information

Henrich: dear aliens, to understand the Western mentality, travel to the Middle Ages

Ask.

Do you find it difficult to explain his great thesis about culture-driven genetic evolution?

Response.

We are a cultural species.

More than any other animal we depend on the learning of other people.

This gives rise to a second system of heredity: biological-cultural coevolution occurs alongside genes, a rather large development in our understanding of human evolution.

You look at a human, and you can investigate the genes that they have inherited from their parents, but that person has also acquired beliefs, values, practices, norms, languages, ways of thinking, a great cultural heritage from their parents and other members of their community. .

All of this jointly affects the behavior of people.

Culture, like genes, accumulates over generations.

Q.

The final result is something so elaborate that no one originally could have created it or even imagined it. Does the same happen with knowledge?

A.

We think that culture is probably at least a million years old and this is a long time for it to affect the genetic evolution of our species.

It's similar to tools, which get more complex as time goes by.

Culture, like genes, accumulates over generations.

It is a second inheritance system

Q.

All technology, but especially objects like spears, are still considered artificial and alien to us, when we would not have survived without them.

R.

Yeah, people still do this, we have this mind-body dualism where we think of culture as separate from biology.

But what can be seen throughout history is that the biological and cultural aspects are inseparable.

This can really be understood in light of the fact that we are a species that has culturally transmitted how to make fire and cook.

Our little teeth require cutting tools to chew the meat and fire in the kitchen to soften the roots before eating them.

We have been dependent on technology and culture from the beginning.

Humans don't innately know how to make fire, but we can learn it.

Spending so much time digesting cooked food has been modifying our physiology and anatomy, leading to a short colon and a small stomach,

Q.

Cultural evolution has modified us so much that, despite being hunter-gatherers for much of our species' history, if any of us were dumped in the woods now, we wouldn't survive.

R.

Sure, that's right, because we have already become a species that cannot live without its culture.

Other animals do not require it to find food or build a nest, but we do need a great deal of cultural information.

We only survive if we interact.

It is the secret of the success of our species, and it lies in the capacity we have to learn from others.

Joseph Henrich's Field Ethnography Experiments Examining Cultural Transmission and Social Norms, in the Yasawa Islands, Fiji.Harvard

Q.

Are cultural differences enough to explain the diversity that occurs among populations in the world?

A.

Doing ethnographic fieldwork during my doctorate as an anthropologist in Peru, I realized that only cultural analysis for the study of human behavior was inadequate.

So I decided I should read psychology, political science, Elinor Ostrom's work on community resources or Kahneman and Tversky's decision making, I also did a lot of studying behavioral economics.

All my research since then has been multidisciplinary, a recombination of social sciences and biology.

Q.

All that decades-long work leads to your new book, How Did the West Become “Psychologically Peculiar”?

R.

I wanted to explain the psychological diversity that we have found, especially the global one in contrast to that of the countries that we group as

rare

.

The map of Western thought begins with individualism and analytical thinking, and a characteristic called impersonal sociality, the trust in cooperation with strangers.

As an explanation, I suggest that the family organization plays an important role.

Families are the first institutions humans encounter in the world and they shape many aspects of our relationships, they affect the way people think.

And it turns out that many populations of European descent have unusual families, which tend to be small, nuclear, and monogamous, compared to the much larger, even clan-wide, family networks we find elsewhere.

Throughout history, biological and cultural aspects are inseparable

Q.

But then why are parts of Europe unusual in this perspective?

R.

I continue the work of anthropologist Jack Goody who long ago argued that Europe was peculiar because of decisions made by a branch of Christianity, which became the Roman Catholic Church during late antiquity.

The Church made a lot of decisions about incest taboos, such as the ban on marriage between close relatives, which led these extended kinship networks to become small monogamous nuclear families.

Of course, this is taking place at different rates within Europe, which explains the great variation across the continent.

It is important to stress that there is no monolithic Europe.

And then I look at a lot of other institutions that come out of this process.

Once families are removed as the central structure,

people have to find other institutions for production and social security, care for the elderly, orphans, widows... So we have guilds or universities, and many more, which lead to increasing urbanization.

All this makes emerge The Industrial and Scientific Revolution, and the Enlightenment.

Q.

And it all started when you realized that the academic research samples you were working with were biased by having only university students, already the most

peculiar

of the

rare

?

R.

That's right, in 2010 I published it in the Department of Psychology and Economics at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver (Canada), together with psychologists Steven J. Heine and Ara Norenzayan.

We had all noticed that in the areas in which we worked, the populations most studied by psychologists were unusual in global distribution.

And that led us to create the acronym

weirdos

, as a way of pointing out a problem in social psychology.

The social sciences for decades have made generalizations about human behavior based exclusively on

rare

subjects , when most of the world is not.

The social sciences had been for decades making generalizations about human behavior based solely on a

rare

subject —Western, educated, industrial, wealthy, and democratic—when most of the world is not.

Q.

Did the Church come to legislate against itself during the Middle Ages?

A.

Many of the things that the Church adopts are actually at odds with doctrines found in the Bible.

Thus, for example, the prohibition of polygamy, which was rampant in the Old Testament.

I am also interested in the origins of Protestantism, it seems to me a very strange religion that requires analysis.

Max Weber used it to try to explain aspects of the commercial companies that were developing.

But from my point of view, as an anthropologist, I try to present a longer-term historical perspective that could answer how you arrive at such an individualizing process.

Q.

Is it an unintended consequence of Protestantism, due to literacy, because they needed to read the Bible for themselves?

R.

Yes, the bottom line is that Protestantism compared to Catholicism is more focused on the mental states of the person.

There is no interface between the individual and the divine.

It's just you and god.

The person is at a disadvantage in front of his deity, and must create his own relationship.

Q.

Which, you defend, causes the emergence of psychological differences in the last centuries in the European population.

A.

You see variation across all kinds of domains.

Europeans have the best data on individualism and independence, conformity and obedience, trust and fairness.

Parameters that vary a lot in the European countries themselves.

In fieldwork, if someone breaks a common practice without being criticized, it was customary;

but if it is rejected by all, what was violated was a norm

Q.

Are trade friendly countries a catalyst for these changes?

R.

The change in prosociality.

In the old world, the model of interpersonal relationships prevails, where you build close and lasting friendships within a community, so if you need help, you try to think of who your cousins are to help you out.

When you begin the transition to a more impersonal prosociality, you have a lot of interactions with strangers.

You are looking for the best person in your job, there is more competition in the market.

There are more exchanges and that leads people to cultivate other dispositions like wanting to be honest or smart.

Business populations tend to favor more impersonal socializing, and this leads people to trust and cooperate more with strangers.

Q.

Transgressing a rule, especially when it is a tradition, can leave one very alone;

but even when they are mere social conventions, and not laws.

A.

Exactly, that's right.

Doing field work with people, we present scenarios where someone has allegedly broken a rule, and we ask for their opinion.

If the subject is heterodox, he is in a minority with respect to a common practice, but does not receive criticism from others for disagreeing, it is a mere custom without repercussions.

But if there is a general rejection that considers it a "bad action", the broken was a norm.

Immigration powerfully energizes innovation;

banning cultural miscegenation would kill some of our most precious legacies from previous generations

Q.

The book deals in depth with the reduction of violence.

Has this type of control via cultural norms, once community kinship ties are broken, have they pacified us?

A.

You can think of it as a change in norms from a world with more intense kinship to an individualistic one.

In a world of highly kinship societies, one often has a strong notion of honor.

You uphold loyalty to your group, your family, clan or tribe, and the country.

If you are in a bar and someone offends you by attacking one of those things it can lead to violence.

Whereas in an individualistic world, where everyone is trying to sell you their goods, whether it's a friendship with potential business interest or some new shoes, you have to cultivate more marketable ties.

You can't immediately turn to anger or appear hostile.

You must know how to negotiate, since not everyone will agree with you.

So you're more patient and you're less concerned about honor.

No threats, basically.

Q.

Does immigration and the open door policy affect the emergence of new ideas and economic growth?

R.

Yes, the evidence on this is clear.

It is the conclusion that is obtained from different sources: immigration powerfully energizes innovation.

And the reason is, and this is something I emphasize in the origins of the Industrial Revolution, that most new ideas—whether it's the steam engine or Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation—are reformulations of previously existing ideas.

That's why you have to bring together a variety of people and have them freely exchange novel hypotheses.

And the larger the population of heterogeneous minds becomes, and the more plural exchange of ideas becomes popular, the more rapid and creative innovation will result.

One example is the United States, where you can look at the history of innovation by studying its census, if you go back at least to 1840, and even earlier.

If you check it against the patent database you find that the counties that had more waves of immigration subsequently produced more knowledge and better cited studies.

Creativity can be studied through that kind of evidence.

More information

Javier Sampedro: 'The strangest people in the world', an explanation of how culture changes the brain

Q.

Could it be dangerous to associate democratic institutions or the progress of countries with psychological differences between populations?

Aren't you afraid that racists will use you to support nativist political agendas?

R.

White supremacists hate this book because it really undermines their view that biological differences are due to genes and are somehow deeply racialized.

In the book I argue how Europe in the year 1000 was a wasteland.

The global technology and business cooperation leaders were the Middle East and China.

But, I analyze, why did Europe emerge as a power after 1500 and begin its global expansion?

Then I expose the theory of cultural evolution, which arises accidentally because the Church formalized some rules on marriage and the family, with a series of subsequent consequences.

It's not about European geniuses or anything like that: it was the result of the strange religious taboos on sex.

Then I look at the variability within Europe itself and show that it has nothing to do with white people.

It really depends on the details of the history of specific places in Europe, and I choose to reference Italians or British and the differences within regions of countries, and I also research China and India, with special attention to different family models. .

This totally belies a racialized point of view.

I think it's important to point out that part of the problem is the current state of public discussion, where by wanting to offer a scientific explanation for why the world is the way it is, some are implying that you're supporting white supremacism, when in fact I'm dismantling it.

I have had many problems with them.

It gives the feeling that simply if you talk about certain issues you are already on the side of racism.

But it's not like that.

The best antidote to the racial pseudoscience of white supremacism is more real science, and not a debate vacuum where we can't discuss ideas.

Q.

So, do we cancel criticism of cultural appropriation?

R.

No, of course we must worry about the looting of indigenous populations and share in the economic benefit that knowledge brings to the whole world.

That is a problem and there is a lot of room left to do.

Having said that, it is undeniable that most innovation is a recombination of ideas from different societies.

So you shouldn't try to stop taking ideas and remixing them.

Rock 'n' roll, steam engine parts can be traced all over the world or, for me the best example, food.

A pizza has tomatoes that come from the New World, but were added in Naples, Italy, by people who had common flatbreads in the Mediterranean region.

A recombination that they later brought to New York and New Yorkers went crazy over the idea and did all kinds of interesting experiments with food.

So yes, banning cultural miscegenation would kill some of our most precious legacies from previous generations.

You can follow

MATERIA

on

,

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/RVDFPGY2WNC6ZCIVCNQNJWWK3U.png)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/BS6KLR7HWVHDBPE2NL7LDTVNKE.jpg)