It's a piece of paper just 21.5 by 15 centimeters.

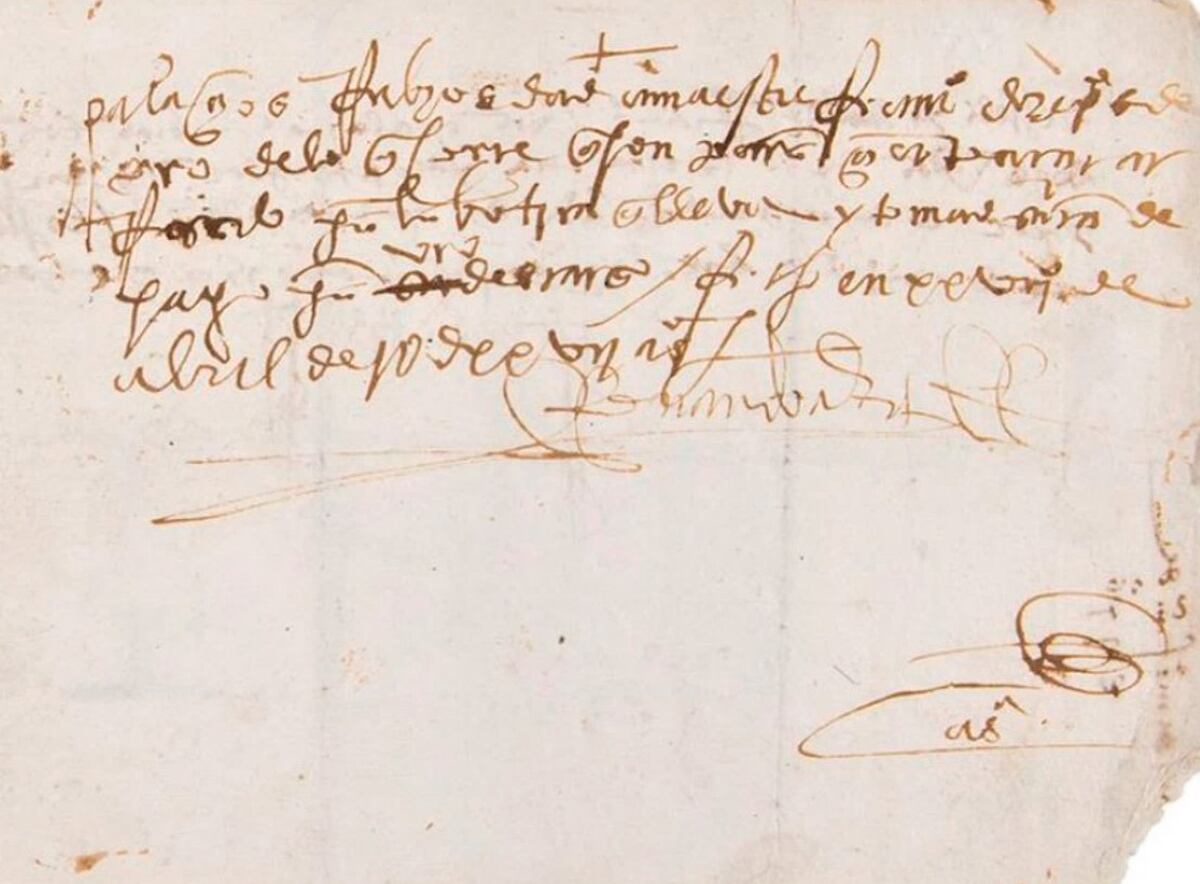

"Palaçios Rubios give Master Francisco twelve gold pesos of what he thinks are for a certain pink sugar for the apothecary he runs and take a letter of payment for your discharge, signed on April 27, 1527", it reads on the front .

These are the words that Hernán Cortés gave to his butler Nicolás de Palacios Rubios almost 500 years ago, a payment order to buy a product similar to the brown sugar that is currently consumed.

Words that were stolen from Mexico at least 30 years ago and ended up in unthinkable places, like a museum in Wichita or a collector's drawer in Florida.

"I received master Francisco de vos Palaçios Rubios the twelve gold pesos contained in this other part and they are for the pink sugar or and for bos given, the signature of my name, or today May 13, 1527 years", it is written on the back.

The document dates from when Cortés was on an expedition through Central America, probably in what is now Honduras.

The payment order and other files remained stored for four centuries in the Hospital de Jesús, the oldest in America and founded by the conquistador himself on Avenida 20 de Noviembre in Mexico City, in the same place where legend says that in 1519 the Spanish soldier met for the first time with the

tlatoani

Moctezuma Xocoyotzin.

The Mexican Government declared on December 24, 1929 that all the files found in the Hospital de Jesús were patrimony of the nation and, after issuing an official decree, integrated them into the catalog of the General Archive of the Nation.

The twists and turns that life takes and the traffic in cultural goods caused the document to appear in another catalogue.

" Incredibly rare

payment

order to buy pink sugar signed by the conquistador Cortés," reported the auctioneer RR Auction of Boston, Massachusetts last May.

The manuscript, iron gall ink on cotton paper, was placed in auction lot 168 with a starting price of $18,626.

The back of the Hernán Cortés manuscript, stolen from the General Archive of the Nation of Mexico. FBI

That was what a researcher who attended an event where the director of the General Archive, Carlos Ruiz Abreu, participated.

More than a complaint, it was a comment and that comment became an instruction: recover the document at any cost.

Ruiz Abreu notified the institution's legal team on May 25.

“It is a document with mysticism, with historical relevance due to the fact that it has the signature of Hernán Cortés”, explains Marco Palafox, the director of Legal and Archival Affairs.

“But the main trigger for all this was that it was stolen from us and we cannot allow things stolen from the General Archive of the Nation to remain outside.

That was the instruction we received,” he comments.

"It was a mission against the clock," says Palafox.

"There were a lot of nerves," he confesses.

If the manuscript was sold before the authorities arrived, they could have lost sight of it forever.

There were 20 days left until the auction ended.

The battle against plunder

Mexico has started a battle against the looting and trafficking of its history.

It is an order that comes from above, the protection of cultural property has risen to the top of the priority list of the Government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

In three years, for example, more than 9,000 archaeological pieces have been recovered.

The problem is that fighting usually takes time.

The diplomatic and legal channels of complaint, at least the traditional ones, are paved with bureaucracy.

Palafox explains that the moment called for an unorthodox exit and so it was decided that Marlene López, the deputy director for the Protection and Restitution of Documentary Heritage, would call an FBI complaint line, similar but not exactly the same as 911.

"Before concluding the call, they told me that it was not certain that they would give me an answer, that there was a possibility that they would not attend to my complaint, but that, in that case, a person from the Federal Bureau of Investigation would contact me shortly," Lopez account.

The call was made on June 6, according to legal documents to which EL PAÍS has had access.

Less than an hour and a half later, the FBI began to investigate.

As the proceedings began, Mexican officials began putting together the legal strategy to prove that the document was from Mexico.

They contacted Carmen Martínez, a researcher at the University of Valladolid who is an expert in Cortés's manuscripts, to prove that the paper belonged to the Hospital de Jesús fund, and they carried out a systematic analysis to trace all the payment orders issued by Cortés and where they were kept. .

Martínez had already been key in recovering 16 court documents that were going to be auctioned in New York last year and were finally repatriated in April.

The next step was to prove that the manuscript had been stolen.

Between 1985 and 1986, the General Archive ordered the collection of the Niño Jesús Hospital into pages.

What was done was to put an escartivana on each manuscript, a strip of paper or cloth that is attached to the loose leaves to facilitate binding or that whoever consults them can turn the page.

The Mexican officials realized that the file kept the escartivanas and the folios, but not the original document.

In the manuscript it is also observed that the part where the folio number was annotated with red crayon was intentionally torn out.

The investigations showed that in 1993 a backup of the file was made on microfilm, but at that point Cortés' paper was no longer in the possession of the Archive.

Thus they were able to determine the date of the theft: 1993 or before.

Who took the role then?

The Archive keeps a record of the files that each user consults in blogs.

The problem is that normally it is not an individual document that is lent, just a manuscript, but rather a whole fund or a box of papers, and tracing is more difficult.

In any case, while seeking answers from the FBI, the institution filed a complaint with the Attorney General's Office (FGR) for the theft of files so that it could provide international assistance in the case in the United States.

After the theft in Mexico, a person identified by the initials JK bought the manuscript at auction in the early 1990s in the United States.

JK is the founder of the Museum of World Treasures in Wichita, the largest city in Kansas, and kept it on display for more than 20 years.

After his death, JK's family consigned the item to be auctioned in Los Angeles by Goldberg Coins and Collectibles.

Another person, only identified as RN by US justice, bought the manuscript from the Goldberg auctioneer in 2019 and took it to his home in Englewood, Florida.

In May of this year, RN turned the document over to RR Auction, the Massachusetts auction house, to be purchased by the highest bidder.

The role of auctioneers

The case has raised questions about the role of auctioneers as accomplices in the trafficking of stolen cultural property.

“Before the Cortés manuscript was offered for auction in 2022, a specialist told RR Auction that similar manuscripts signed by Cortés had been stolen and that it was possible that this manuscript was also stolen,” reads an affidavit from a FBI agent.

It was not the first time that RR Auction had tried to sell the document.

In 2020 it went on sale, but did not exceed the reserve price and was returned to RN

This time, the auction site received 22 bids, until the FBI stopped the auction on June 8, two days after the call with Lopez.

“As soon as they contacted us we stopped the sale, notified the consignor and there was no problem with them,” Mark S. Zaid, an attorney for RR Auction, told

The New York Times

.

On June 20, the complaint was filed in Mexico with the FGR.

The headquarters of the General Archive of the Nation, in Mexico City. Hector Guerrero

The General Archive of the Nation sent a delegation to Boston on August 28 to verify that the manuscript was authentic.

López, a historian and restoration specialist, traveled accompanied by Kenneth Smith, the FBI liaison at the US Embassy in Mexico City.

“It was a long and heavy trip,” says López.

"We had a suitcase full of supplies, materials, specialized and delicate equipment," adds the lawyer.

They packed, among other things, a microscope, special light sheets with which some aspects of the materials can be seen, and they borrowed an ultraviolet light from Harvard University that they could not document at the airport for security reasons.

The technical analysis, presented on October 25 to the FGR, corroborated that it was the original document.

"The recovery of this national treasure stolen from Mexico and its people not only preserves an important part of the country's history, it also reflects the commitment to seek justice for victims of crime here and abroad," said the special agent of the bureau of investigations Joseph Bonavolonta, after the United States announced the seizure on November 22.

But the manuscript's journey is not over yet.

Matters of the judicial process still need to be resolved, procedures between the authorities of both countries and wait if RN will cede ownership of the document or go to trial.

"It is not on the door for this document to return to Mexico soon," says Palafox, although he qualifies that it is still early to enter into speculation about a possible repatriation.

“It is not only a legal issue, it is a moral issue: assets that are the patrimony of the nation, of the people have been removed, trafficked and profited improperly,” says Jorge Islas, consul in New York and a key player in their recovery. the other 16 courtesy documents last year.

Islas found out about that auction while having coffee for breakfast and reading the newspaper.

Months later, the consulate's complaint found a diplomatic channel for part of that file to be returned without the need for a trial.

“Not only have they been delivering recovered treasures to us,” says Islas, “they have already realized that Mexico is not going to let one pass and this is generating alarms to the extent that the large museums are already refusing to receive lots like these as donations, They don't want to have problems."

The battle has several open fronts and you have to go case by case.

For the lawyer Palafox, the legal route is a slower option, but it can generate legal precedents that help the country to recover more assets in the future: from documents to archaeological pieces.

Only the General Archive has four cases pending resolution, the majority in the United States.

And he is considering ways to avoid thefts such as using dogs, molecular scanners or hypersensitive scales, although nothing has been decided yet.

There are denunciations, legal strategies, a greater knowledge of the

modus operandi

of the traffickers and an increasingly closer possibility that a stolen manuscript from almost 500 years ago will return home.

subscribe here

to the EL PAÍS México

newsletter

and receive all the key information on current affairs in this country