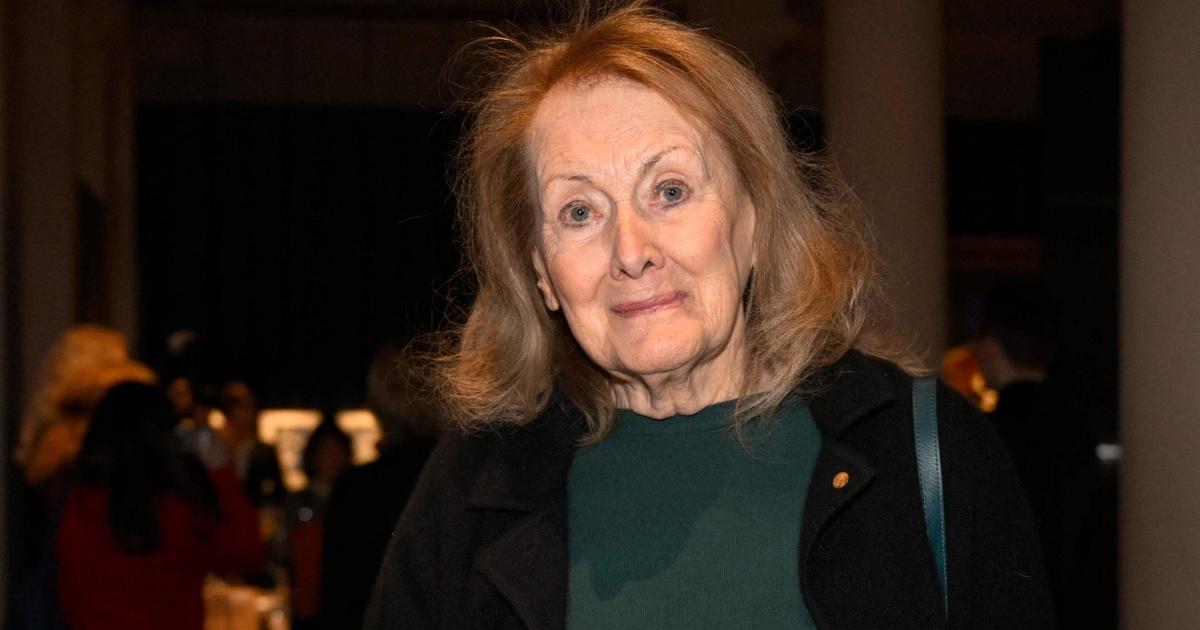

The first French woman to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature since the founding of the prestigious awards in 1901 granted an interview to AFP on Tuesday in which Annie Ernaux affirms that the Nobel is

"an institution for men"

, adding:

"It 's

manifested by this taste for tradition, in the costumes.

It seems to me that the attachment to traditions is perhaps more masculine, basically, we transmit power to each other like that.

Then:

"Speech has still been almost always monopolized by men and I have noticed that women are often less verbose in their speech than men, knowing full well that they are more practical."

The lady of Cergy had the possibility, through the speech that she will deliver at 5 p.m., to take up this word confiscated by the men.

The least we can say is that his very short text (one of the shortest probably ever written in the history of the Nobel) will not be remembered.

Returning to her favorite phrase, "I will write to avenge my race", recorded sixty years earlier in her diary and, excuse me a little, echoing Rimbaud's cry, "I am of an inferior race from all eternity", Annie Ernaux, after a touching return to her Norman roots, has returned to basics, to this

“area that is both social and feminist”

.

To avenge my race and to avenge my sex would henceforth be one.

Read also“Avenge his race and his sex”, discover the very political speech of Annie Ernaux at the Nobel Academy

To this need for an "insurgent writing", to fight an "attitude of dominated", of "immigrant from within", to fight the violence of men, violence in Europe, in Iran, in Ukraine... Naive that we are, we would have liked more elevation, emotion, literature.

Suddenly, we remembered Camus, in 1957:

“At the same time, after having said the nobility of the profession of writing, I would have put the writer back in his true place, having no other titles than those he shares with his companions in struggle, vulnerable but stubborn , unjust and passionate about justice, building his work without shame or pride in the sight of all, constantly torn between pain and beauty, and finally dedicated to drawing from his double being the creations he stubbornly tries to build in the destructive movement of history.

Who, after that, could expect ready-made solutions and fine morals from him?

The author of

The Stranger

continued:

“Truth is mysterious, fleeting, always to be conquered.

Freedom is dangerous, hard to live with as much as it is exhilarating.

We must walk towards these two goals, painfully, but resolutely, certain in advance of our shortcomings on such a long road.

What writer, then, would dare, in good conscience, to become a preacher of virtue?

As for me, I must say once again that I am none of that.

I have never been able to renounce the light, the happiness of being, the free life in which I grew up.

But although this nostalgia explains many of my mistakes and faults, it has undoubtedly helped me to better understand my profession, it still helps me to stand, blindly, with all these silent men who cannot bear, in the world,

Read alsoThe Nobel is an institution "for men", according to Annie Ernaux

Closer to home, how can we forget the moving text by Hungarian Imre Kertész in 2002?

Deported to Auschwitz at the age of 14, the first Jewish writer to win the Nobel, ended his speech with these words: "

So I died once so I could go on living – and maybe that's my real story.

Since this is so, I dedicate my work born from the death of this child to the millions of deaths and to all those who still remember these deaths.

But since it is ultimately about literature, a literature which is also, according to the arguments of your Academy, an act of testimony, perhaps it will be useful in the future, and if I listened to my heart, I would even say more: it will serve the future.

Because I feel that by thinking about the traumatic effect of Auschwitz, I touch on the fundamental questions of human vitality and creativity;

and in thinking thus of Auschwitz, in a perhaps paradoxical way, I think more of the future than of the past.

In 2006, the Turkish Orhan Pamuk built his entire intervention around his father's suitcase, found after his death.

An object filled with manuscripts and notebooks.

The act of writing inspired him with this unforgettable passage:

“I write because I want to.

I write because I can't do normal work like other people.

I write so that books like mine will be written and read.

I write because I am very angry with all of you, with everyone.

I write because I enjoy being locked up in a room all day long.

I write because I can only endure reality by modifying it.

I write so that the whole world knows what kind of life we lived, we live me, the others, all of us, in Istanbul, in Turkey.

I write because I like the smell of paper and ink.

I write because I believe above all in literature, in the art of the novel.

I write because it's a habit and a passion.

I write because I

am afraid of being forgotten.

I write because I enjoy fame and the interest it brings me.

(…) I write in the hope of understanding why I am so angry with all of you, with everyone.

I write because I like to be read.

I write telling myself that I have to finish this novel, this page that I started.

I write thinking that this is what everyone expects of me.

I write because I believe like a child in the immortality of libraries and the place my books will hold there.

I write because life, the world, everything is incredibly beautiful and amazing.

I write because it is fun to translate all this beauty and the richness of life into words.

I write not to tell stories,

but to build stories.

I write to escape the feeling of not being able to reach a place where one aspires, as in dreams.

I write because I can't be happy no matter what.

I write to be happy.”

A year later, the English novelist Doris Lessing, a committed writer if ever there was one, reflected on her youthful years spent on the African continent.

“My mind is full of sumptuous memories of Africa, which I can bring back to life and contemplate at my leisure.

These sunsets, gold, purple and orange, which invade the evening sky!

The aromatic bushes of the Kalahari Desert, blooming with butterflies, moths and bees!

Or me sitting in the pale grass of the banks of the Zambezi with its dark, glistening waves, above which all the birds of Africa soar.

Yes, elephants, giraffes, lions and all the rest, there were plenty of them, but what about the marvelously dark night sky, still unpolluted, riddled with effervescent stars!”

, she wrote.

And she added:

“Other memories still come to me.

A young African, maybe eighteen, is in tears, planted in what he hopes will be his “library”.

A passing American, having seen his library empty of books, had sent off a whole crate.

The young man had taken them out one by one with respect before rewrapping them in plastic.

“But, we object, these books have indeed been sent to be read, come on!

“No,” he replies.

They would get dirty.

And where can I get more?

And what about the speech of Patrick Modiano, the last French crowned before Annie Ernaux.

It was in 2014.

“Curious solitary activity that of writing.

You go through moments of discouragement when you write the first pages of a novel.

You feel like you're on the wrong track every day.

And then, the temptation is great to go back and take another path.

We must not succumb to this temptation but follow the same path.

It's a bit like being behind the wheel of a car, at night, in winter and driving on ice, without any visibility.

You have no choice, you can't go back, you have to keep going, telling yourself that the road will eventually be more stable and the fog will clear.

Dora Bruder

to continue:

“On the point of finishing a book, it seems to you that it is beginning to detach itself from you and that it already breathes the air of freedom, like children, in the classroom, on the eve of the summer holidays.

They are distracted and noisy and no longer listen to their teacher.

I would even say that as you write the last paragraphs, the book shows you a certain hostility in its haste to free itself from you.

And he leaves you as soon as you have written the last word.

It's over, he no longer needs you, he has already forgotten you.

It is now the readers who will reveal it to itself.

You experience at this moment a great emptiness and the feeling of having been abandoned.

And also a kind of dissatisfaction because of this link between the book and you, which was cut too quickly.

This dissatisfaction and this feeling of something unaccomplished pushes you to write the next book to restore the balance, without you ever succeeding as the years pass, the books follow one another and the readers will speak of a '' work''.

But you will have the feeling that it was only a long flight forward.

»

Annie Ernaux, whose books were reprinted in 900,000 copies by Gallimard after the announcement of the Nobel, will receive a check in Sweden for around 900,000 euros.

We hope that the one who calls herself a “social defector”, now a millionaire, will make good use of it.

A bit like Dominique Lapierre, who died a few days ago.

The author of

The City of Joy

made, for years, donations to India to treat lepers in particular, thanks to the colossal sales of his bestsellers.