It was an isolated case.

A

rare bird

of probability.

One of those few unfortunate patients who populate medical school textbooks as footnotes that statistical anomalies are also possible in an operating room.

That's what they thought, at least, when it all started.

The first woman arrived at the Durango Maternal-Child Hospital on October 14.

She had terrible headaches.

A month earlier, on September 15, she had undergone a caesarean section at the Hospital del Parque.

The anesthesiologist who performed the operation also worked at the Maternal-Child Hospital — having jobs in various clinics is a common practice among doctors in Mexico to fill the gap in salary — and decided to treat her there.

No one could have suspected it, but the first domino had just fallen, revealing an outbreak of meningitis caused by a fungus that has already killed 25 women, one man, and infected more than 70 people.

Although, then, the word meningitis was just a rumor.

Christian Herrera (33 years old) arrives one day in early December at a cafeteria with views of the Durango cathedral.

He has just finished an eight to eight shift at Maternal-Child and is still wearing work clothes under a black jacket.

He has a large face, close-cropped hair, square glasses, and sideburns that fade to a scruffy goatee and frame his features like a photograph frame.

He, a gynecologist, was one of the first doctors to care for that first patient.

Amandina Catrala

The woman underwent several tests but nothing added up.

They were unable to find a diagnosis that would justify the nausea and dizziness, those stingers that dug into her skull for no apparent reason.

The neurological examination did not give "frank" beginnings of meningitis, explains Herrera, "but something was happening, the pain did not go away."

The first clue came from the hand of a lumbar puncture: extracting a sample of cerebrospinal fluid and analyzing it chemically.

They found a glucose deficit: hypoglycorrhachia, in medical language.

—It is an indirect piece of information that indicates that there is an infectious process: I left three plates and someone ate two.

Doubt had come to settle.

"We thought there was something, but we didn't know what."

They applied a "suspicious treatment": antibiotic and steroids to "hit whatever she was there and help her reduce inflammation."

On October 20, the second patient was admitted with the same symptoms.

On the 21st she was the third.

The 23rd the fourth.

The analyzes of all four presented hypoglycorrhachia.

All had received surgeries at the Hospital del Parque, all with the same anesthesiologist.

The rumor began to take shape.

—We began to think that it was not a coincidence.

“I saw myself again in the pandemic”

The anesthesiologist, who is under investigation and has declined to speak to this newspaper, was concerned.

He didn't understand why four of his patients were suffering from these symptoms, Herrera says.

The women's pain levels were through the roof and they were given Dexamethasone.

"Clinically, they improved a lot," says the gynecologist, "after that medication, some stopped having symptoms."

“At that time, the main suspect was the same anesthesiologist.

But other cases began to be reported with other specialists, ”he continues.

—There I said: 'Something is happening'.

I felt afraid, I saw myself again in the pandemic.

It arrived on Friday.

For the following Monday, the first patient had a lumbar puncture scheduled to monitor her progress.

But over the weekend the calm was broken.

The woman began to convulse.

She suffered an aneurysm that ended in bleeding.

She went brain dead.

“Here, euthanasias are not performed, the vital signs are allowed to disappear.

It was the first brain death, but it was not the first official deceased”, explains Herrera.

It was October 24 and everything had just begun.

Doubts gradually began to dissipate.

They applied the standard treatment for meningitis caused by a bacterium, the most common form in which the disease presents.

A neurologist ventured the hypothesis that the origin could be a fungus.

“In the world of meningitis, those caused by fungus are very rare.

Almost all of them are immunocompromised patients or who have suffered severe trauma or neurological surgery”, says Herrera.

“In terms of statistics, we were entering the weirdest of the weird.

The problem was when we started seeing it in other patients.

Until then we were still clinging to the theory that it was an isolated case.

A relative agreed to perform a necropsy on the body of the first victim.

And the suspicion was confirmed: it was

Fusarium solani

, a fungus.

The rumor had become certainty.

“That was when the real terror began.

The other three patients followed the path of the first.

After about ten days of apparent improvement, they all suffered hemorrhages that led to brain death.

Cases began to multiply in other hospitals.

The health authorities decided to transfer all those infected to the General Hospital 450 and two other public centers where day-to-day life became hell.

Maribel Nava, mother of Nancy, one of those infected, described it as a nightmare: “Many girls convulsed and the doctors ran from one side to the other.

My daughter told me: 'Why are you shouting for help?'

I lied to her because she knew what was going on.

I have not detached myself from my daughter, I do not want to take my eyes off her ”.

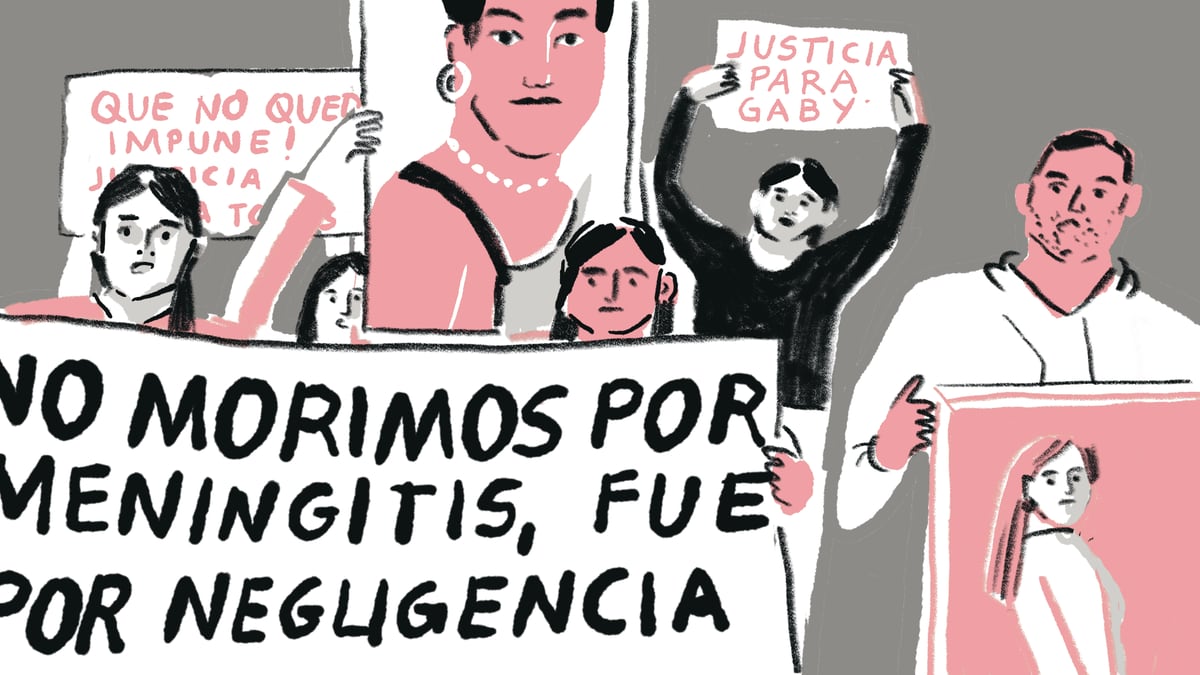

The fear of impunity

The brain deaths triggered an investigation that identified four private clinics as the origin of the outbreak: Hospital del Parque, San Carlos, Dikcava (which did not even have a license) and Santé.

The fungus appeared in four batches of a local anesthetic, bupivacaine, used for short operations, mainly caesarean sections.

Hence, the vast majority of those affected are young women.

After analyzing samples of the drug, the Federal Commission for the Protection against Sanitary Risks (Cofepris) established that there was no original contamination in the drugs, but it did identify the presence of "fungi and bacteria" in the four health centers.

Amandina Catrala

A health worker who worked in three of them and prefers not to give his name describes them as “shady” places: “One was more or less good, but the smallest one was practically a house adapted to see patients.

It was never clear who the owner was, I think not even the employees themselves knew it”.

The owners of the clinics are in the crosshairs of the Prosecutor's Office, which issued seven arrest warrants against them on the 5th, but it was too late and the suspects had already escaped.

Their whereabouts remain unknown.

"In a matter of two weeks there were already more than 40 cases," says a doctor from 450, in charge of caring for meningitis patients, who prefers not to give his name.

“We didn't know for sure how many people had undergone interventions.

They said it could be about 500. I did the math and thought: 'Where are we going to put 500 people?'”.

The toilet's estimates fell short.

Although the disease is not contagious, the Durango Health Secretariat (SSD) identified more than 1,800 people at risk having undergone surgeries since May in the centers involved.

It was a key task: according to a study, mortality from the disease can drop from 50% to less than 10% if those infected receive treatment before symptoms appear.

The treatment seems to work in some cases.

The SSD has confirmed twelve medical discharges, although in an interview with this newspaper, Irasema Kondo, the head of the agency, acknowledged that "once [patients] present intracranial hemorrhage, it is very difficult for them to survive."

There are still more doubts than certainties, all the experts consulted agree in assessing the outbreak as "historic": there are hardly any references in the scientific literature or previous experiences that mark the way forward.

The precedent is being set in Durango.

Two months later, the end is still far away.

Along the way, 26 lives have been lost;

more than 40 children have been orphaned and the high mortality of the disease indicates that there will be more deaths.

There are no culprits, only seven fugitives and no one who has assumed political responsibility.

After death, the battle against impunity begins for families.

subscribe here

to the EL PAÍS México

newsletter

and receive all the key information on current affairs in this country