As a teenager, Orhan Pamuk wanted to devote himself to painting.

It is finally the writing that he chooses, at the age of 22, for fear of being only a rapin.

But in 2008, in a color store in Massachusetts, her first love resurfaced.

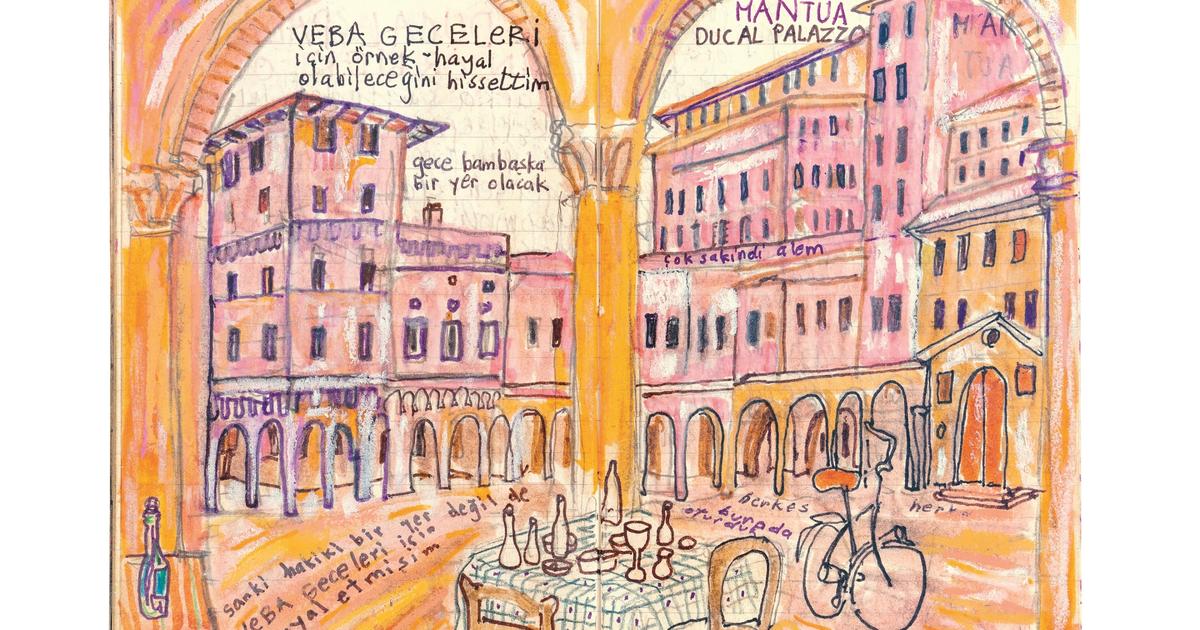

Since then, he has used his markers and pigments daily to record his emotions, his doubts, his reflections on current events… These facsimiles, where texts and drawings intertwine, are brought together in

Souvenirs des montagne au loin.

Sketchbooks (Uzak Daglar ve Hatirlar) (1).

A precious gift for young writers and the most loyal readers.

Because the author undoubtedly delivers the most personal and most intimate part of his work.

LE FIGARO. - You write and draw simultaneously since your childhood. Why reveal these notebooks today?

Orhan PAMUK. -

I have always noted feelings, nocturnal thoughts, reflections on my novels.

Every day I blacken the paper and leave blank spaces in the pages.

I come back sometimes to draw.

I don't plan anything, it's accidental art.

Like an encyclopedia of what I see and what I feel.

Now that I am 70 years old, I understand that my memory is no longer so infallible and that these 22 notebooks, all stored in a box, are a precious material.

The threat of an earthquake also worries me

(a fault in the North Anatolian plate, between the Caucasus and Greece, regularly threatens

Turkey

, Editor's note).

In 2009, I was already writing in a notebook:

“My wish, before I die, is to write a book about the mountains in the distance.

On painting and the fantasy of distant countries, the spectacle of misty mountains.

On this romantic feeling, this love of the landscape so deeply engraved in my heart, my soul.

And of which I do not explain the reason.

The time had come.

Throughout the pages, we come across the protagonists of your previous works. Do you consider this book as the most intimate of your work?

It would be an immense honor to consider this work as an intimate book in the country of André Gide, who gave his letters of nobility to the personal diary.

The choice of pages was complicated.

I asked Antoine Gallimard to send someone to Istanbul to see what we could do with these notebooks.

I met Nathalie, who first chose 450 double pages.

I was then instructed to select half of them.

I first thought about the value of the pages in relation to the interest of the text.

Then there was the aesthetics.

But ultimately, the emotion of memory is perhaps what guided the design.

It's never easy to reveal so much of yourself to the world, but reading Jean-Jacques Rousseau helped me a lot in this direction.

He taught me to distill intimacy into my works.

Because humanity is universal, and that's what makes people buy and read books.

Like me, the characters evolve.

They are alive in my mind, I talk to them.

I'm not afraid of the blank page because if I trust my characters, they show me the way.

And this book brings them to life.

We note your admiration for artists like William Blake, Raymond Pettibon or Cy Twombly. What does drawing have that writing doesn't?

When I draw after drinking a glass of wine, I have the same feeling as when you sing in your shower.

I am happy in a very ordinary way.

Painting is ultimately very accessible.

It is a celebration of sight, a joy, when writing takes us through hurricanes of suffering.

Being a novelist is painful, but it is also what is essential to my balance and gives me a raison d'être.

Many artists have proven that the two practices can mutually enrich each other.

William Blake is undoubtedly the greatest of all the writers of drawing, or, let's say, of the writers who knew how to think text and image at the same time.

But we can also cite Proust or Tolstoy in terms of visual artists.

I aspire to be more like them.

Orhan Pamuk, Nobel Prize for Literature 2006. 2022, Orhan Pamuk, all rights reserved.

Find the other episodes of the series "A book under the tree"

EPISODE 1 -

Marie Couderc and Nil Hoppenot: "On foot, every meter is part of the journey"

EPISODE 2 -

Lucie Azema: "Tea has both a notion of adventure and violence"

EPISODE 3 -

François Sarano: "I have never been afraid when swimming with sharks"

EPISODE 4

- Guillaume Desmurs: “Skiing embodies speed, the cardinal value of modernity”

EPISODE 5

- Philippe Gloaguen: "At Hachette, they call me the laying hen"

Travel has an important place in this book (India, Italy, United States, Russia…), but Istanbul remains omnipresent. Will this city always be the central character of your work?

I believe him.

It is my city of birth and passion.

I have traveled a lot and I live part of the year in New York where I teach at Columbia University.

These destinations bring me energy, a form of inspiration.

But in Istanbul, I am at home.

People speak my language, share my culture and its familiarities.

I am attached to these sounds that I find only here: those of footsteps on deserted pontoons in the heart of the night, the generators of docked boats, the popular melody that comes out of a radio set... In the neighborhood where I live, in Cihangir, life is human.

There is still, close to my house, a greengrocer, a small grocery store.

It reminds me of my childhood, the large family, the turmoil of community life, friendship, happiness.

Even if I moved away from those communities.

I have become a solitary man, walking around town under police escort.

But in a high place, with a clear view, nothing around, I'm safe.

You glorify Istanbul but you have harsh words for the urban transformation of this metropolis. Is it nostalgia?

There is nothing more vulgar than demolishing heritage without even trying to preserve it.

I very rarely go to Nişantaşı, the neighborhood where I grew up, for example.

With its ugly shopping center right in front of the Pamuk building, its fashion chains, its clubs, its bars, its restaurants and its crowds, there is nothing familiar anymore, nothing that makes me happy anymore, Alas.

I knew Istanbul in its fallen splendor as a former capital.

There have been great waves of immigration in recent years and the autocratic rulers have changed the urban landscape to meet their new ambitions.

It makes me sad, but I don't want to be nostalgic.

I often think of this book by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki,

Praise of the Shadow

, on the aesthetics of old Japanese houses.

After the publication, everyone asked him if he would like to live in this type of dwelling again.

The answer was obviously negative, he said he wanted to live with water, electricity and modern comfort!

But that did not prevent him from celebrating this heritage of ancient times.

We must relearn how to glorify the past.

This does not make us reactionaries, far from it.

(1)

Memories of the mountains in the distance.

Sketchbooks (Uzak Daglar ve Hatirlar)

, translated from Turkish by Julien Lapeyre de Cabanes, Gallimard, 396 pages, €39.50.

Memories of the mountains in the distance.

Sketchbooks

, Gallimard.

Gallimard / Photo press