The territory shared by fiction and verisimilitude is exposed in the prologue of the latest novel by Yuri Herrera,

La estación del pantano

(Periférica).

The exile of Benito Juárez in New Orleans serves the Mexican writer to recreate a stage in the life of the revolutionary of which little information is available.

“It is in that gap marked by the full stop where this story takes place.

All the information about the city (...) can be corroborated in historical documents.

This, the true story, no ”, invites you to read the first page of the book: a polysemic story, the one from the days of Juárez, but also the one that emerged from his imagination, the true one.

“It is a parenthesis in the life of Benito Juárez.

All biographies mention this period very briefly.

Another of the things that is invariably said is that it is the period in which he became radicalized and in which he became the most important liberal.

But nobody has any data,” explains Herrera (Actopan, Mexico, 52 years old) in a diner in New York.

Juárez and New Orleans intertwine in the life of the writer, who has been teaching at Tulane University in that American city for a decade.

Although with frequent comings and goings to Mexico.

Regarding La estación del swamp, he continues, “the curious thing is that [that period in Juárez] is a very important black hole, because returning [to Mexico] is when he becomes Minister of Justice and then President, and then the person who will face the French invasion."

A source of unknowns that is “an opportunity to make a kind of plausible imagination, so to speak.

That is what I have allowed myself to do with a few data about his life, with a lot of data about what the city was like and fundamentally with my imagination ”.

“Narcoliterature?

I don't like the etiquette, but one must assume the consequences of dealing with certain topics.

When I published 'Trabajos del reino', drug trafficking was not the main problem in Mexico”

Herrera details his documentation work, until he soaks up the daily life of New Orleans (“the music, the race relations”), of which, he says, entire libraries have been written.

The digitization of The Times-Picayune newspaper helped him to raise the scaffolding.

“It helped me to have a panorama that obviously will never be a faithful reflection of reality.

But yes one of the possible ones about what daily life was like and, specifically, the criminal life of the city, because the red note [chronicle of events] is frequently one of those inescapable data from reality.

And this was an incredibly violent city in many ways, as it still is."

His own life experience as an expatriate also helped, that of "someone who has not been in exile, but who does feel nostalgic, who in many moments feels isolated."

Revolving around space and time, two constant fields in his narrative, this foray into the historical novel is too close for an author capable of breaking the molds of genre and style.

In

Signs that will precede the end of the world

, the second one published (and, like all of them, in Periférica), the story of a young woman who is looking for her brother across the border between Mexico and the United States is mixed with echoes of pre-columbian myths.

In the third,

The transmigration of the bodies

, a black fiction, tells a story of drug traffickers in the middle of an epidemic.

kingdom jobs

, his first work ―highly praised by references such as Elena Poniatowska―, was classified as narcoliterature, this label that was so fashionable a few years ago, the result of the mystification by popular drug culture: “Those labels work for good and for bad.

There are people who have made an academic career out of them;

they also serve to situate a book in a bookstore, or in a kind of public discussion.

I never liked it.

Books have their own life, and one cannot go around the world posting instructions on their lives.

One has to assume the consequences of talking about certain issues at certain times, and when I published Trabajos del reino, drug trafficking, although it was already one of the most important issues, had not become the most important issue in Mexico.”

“Literature does not influence politics.

By the time they read you, the political phenomenon you've written about has already passed."

What is striking in Herrera's speech is the academic precision with which he lays out his ideas.

It may be due to his university education, but the truth is that he powerfully ties each sentence.

Then his literature is pure lava, brilliant, but in conversation a scalpel-like lucidity stands out.

Does the writer consider, by sticking to phenomena of the depth of emigration or drug trafficking, that he makes political or social literature?

“That is something I have never tried to do.

I studied Political Science, a very important element in my look at the world and even in my aesthetic look.

That is, there is a certain way of understanding national tragedies, social tragedies, heroism, betrayal.

But I never try to make a deliberate comment on current living political actors, ”he underlines.

Although it is unavoidable

He assumes that the echoes of the present infiltrate what he writes, he does not try "to intervene in political life from literature."

If some type of literature tries to influence a political phenomenon that is very localized in time and space, he emphasizes, "by the time it has been read, understood and digested, this phenomenon has probably already passed."

The swamp station. Yuri Herrera.

Herrera founded and directed the literary magazine

El Perro

, another example of the strength of the so-called literary journalism in Latin America.

In Mexico, the red note has almost become a genre unto itself.

Almost as much has been written about the supposed symbiosis of journalism and literature as about the death of the novel, but is the influence harmful, beneficial, or simply non-existent?

“I did not come to literature through journalism, but I know many people who did and we have had multiple cases in all countries, at all times: García Márquez, José Martí, Hemingway.

I don't think that literature and journalism feed off each other in terms of how to represent reality.

Literary truth does not depend on data, but precisely on that which cannot be quantified and demonstrated, but which is a true part of the human experience.

Of the red note, he considers that it has its own dimension.

"Somehow it has to suggest that which goes beyond the forensic, and which is how we deal with the emptiness that death leaves us, with everything that surrounds this, with impunity, with sadness."

“The American South has a reputation for being racist, but New Orleans is freaky, liberal, 'queer.'

And the biggest racist of all [Donald Trump] lives in New York."

His experience as a Mexican and Spanish speaker yields interesting reflections that dissect the United States marked by fire by Donald Trump.

To begin with, due to the fact that the second most spoken language in the country is theirs.

“Well, this is a country that has been polyglot, although it has the illusion that it is exclusively English-speaking.

Monolingualism is one of the discourses parallel to white supremacism.

When it was founded, not only Spanish was spoken, but multiple European and local languages.

And Spanish has increasingly become one of the hegemonic languages, I would not say, but it is getting closer to being one of the lingua francas.

What racist politicians do is not going to change this, which is one of the best features of this country among all its egregious features:

Herrera does not spare criticism of the havoc that Trumpism caused in the US or in America, as the country calls itself, to the detriment of the rest of the countries on the continent.

“How many continents are there in the world?” he asks rhetorically.

"Five, right?

In the English-speaking world, in the United States, England, Australia, they are going to answer seven... When we cannot agree on something that can be seen from space, it is much more difficult to agree on something that people have been indoctrinated.

Many people not only have never left the country, but also do not conceive of the existence of other countries.

The United States does not conceive of its culture as a national culture, but as a universal one, and understands that in other countries the language of the United States must be spoken. And there is a huge percentage of people who think that Jesus Christ was American.

I'm not making it up.

But there are more urgent things than the incorrectness of the demonym.

If one thinks of the inhuman conditions close to slavery in which many migrants live…”.

“One does not create out of nothing, spontaneously, but in certain inherited forms.

Of course, we are not hostages of forms.

We can play with them."

His American experience as a teacher, as a white-collar expatriate, allows him to break through the supposedly monolithic reality —as represented in the media, for example— of emigration.

Not even the language resists as a whole to the vital and historical circumstances of the subjects that speak it.

“It is important not to socialize the migrant experience, there are many experiences that have to do with generational changes, with the socioeconomic situation, with the legal situation,” he explains.

From the generations "expelled from their language as a way of survival" to get ahead to those who have had the opportunity to grow up in that of their parents and grandparents.

Those who have had to adopt the language of the place where they have arrived, “which is at the same time the language of the benefactor and that of the exploiter;

in any case,

the language of the powerful”, and those who “in New York, in Los Angeles, in many other cities, have had the opportunity to grow in their own”.

Like in Queens, for example, where a local branch of the Mexican cult of Santa Muerte has sprung up, and where you can live without speaking a single word of English.

“Others of us have already reached adults;

In this sense, of course, the language continues to be our homeland and our territory”.

Herrera teaches Literature in Spanish, and sometimes in English depending on the group.

He now does so as a guest writer at Middletown Wesleyan University (Connecticut).

A town that he arrived at three months ago and that is in the antipodes, in all senses, of New Orleans, not only because of a cold that has him shivering.

“It is too soon to be able to talk about this experience.

But I come from New Orleans, where more than 60% of the population is black, and I am living in a little town called Oldham, with very kind people, a very rich little town, practically white."

The experience has allowed him to further elaborate his notion of racism in the US Far from New Orleans, “an anomalous city in the South, because it is not only a liberal city, but, I would say, a

queer city

in the best sense of the word… Much more free and fluid than any other city where I have been…”, now recalibrates the dimension of the south as a depositary of that scourge.

“I think that the way in which the south is understood in the eastern and northern United States, as that place full of racists —and I'm not saying that there aren't any— is used by others to place the responsibility for racism on it. , as if the most important racist in the world was not from New York, born, raised and enriched there, ”he says, alluding to Donald Trump.

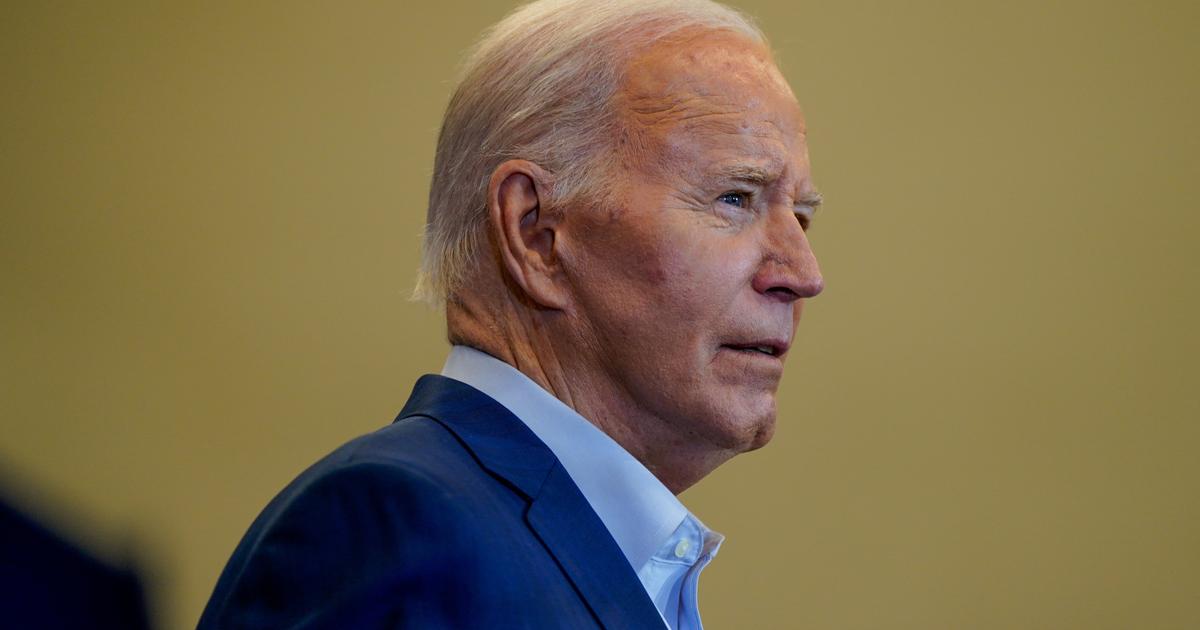

Herrera submits with precise kindness to the photographer's instructions, in a traditional

diner

of Manhattan where the interview takes place.

The photo session continues in the street, between spontaneous comments about plays or the latest in Mexican cinema.

One last thought about creation: “There is a phrase from Chesterton where someone says: 'All the facts point in this direction.'

And the protagonist replies: 'That's nonsense.

Facts are like the branches of a tree, they point in all directions.'

What one does is tie those branches and create meaning.

And one does not create meaning out of nothing, spontaneously, but in certain ways that have been inherited.

Those forms can be myths or they can be genres.

Of course, we are not hostages of forms.

We can play with them."

In the absence of branches, New York provides the confused masts of skyscrapers,

'The station of the swamp'.

Yuri Herrera.

Peripheral, 2022. 192 pages.

€17.90.

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/ILBEAMGUENGA5GZQW2PSQFT7UE.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/Q6GXUFDARZGI5BCOMCTHWWYV4Y.jpg)