There is a particular intensity of symbols in these days near the end of the year;

a gravitation of ancient legends on our secular consciousness.

What is nothing more than an illusory division of dates in the calendar takes on an immediate presence of threshold and border crossing.

Beneath it all beats the astronomical evidence of the winter solstice, the longest and darkest night of the year, which from now on will recede very gradually as the solar length of days advances.

The original legends have such a powerful influence on us, and so unnoticed, like the laws of nature, that due to frivolity or technological arrogance it costs us nothing to ignore.

Whether we want it or not, just as we cannot ignore the daily alternation between day and night, which govern our vital rhythms,

Historians teach us that in the Rome of the early days of Christianity the

Natalis Solis invicti was already celebrated,

the birth or rebirth of the sun after the shortest day of the year.

On top of that substratum, the equivalent story of the birth of Christ on a dark winter night is told, in the same way that a church is erected on the same site where there was a pagan temple.

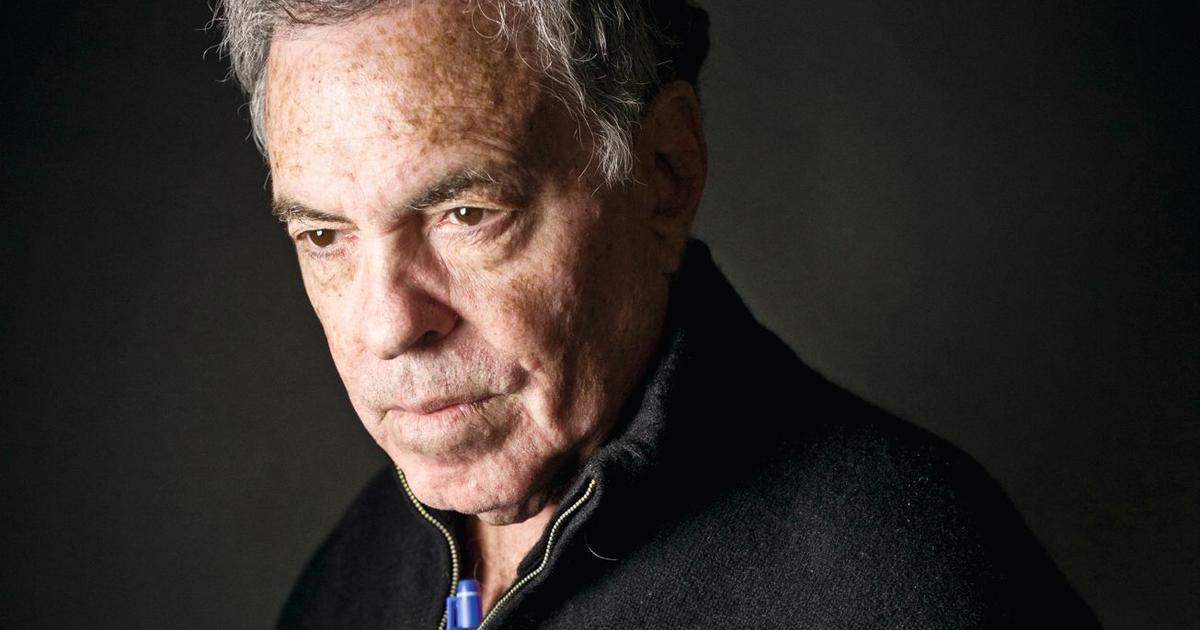

As Juan Arias has recently explained in these same pages, with the cordial wisdom that he brings to everything he writes, most of the familiar details of the Christmas story are imaginary, and not even based on the authority of the Gospels. .

But it is those circumstantial details that feed the poetic and narrative force of a fable that shakes us even more because its historical antiquity has its equivalence with the distance of its roots in our personal memory: and not with conscious memory, so limited and so unfaithful,

Cyril Connolly, so English in his ironic detachment, so demanding in his criteria of literary quality, was shaken by the simple beauty of the Spanish Christmas carol: “Christmas Eve is coming, / Christmas Eve is going.

/ And we will leave / and we will not return anymore.

When I found those lines in Connolly's almost secret masterpiece,

The Unquiet Grave

, I had the sensation of recognizing a familiar and beloved voice in a foreign place.

The sudden anguish they express over the passage of time contrasts with the joy of the music and the chorus that accompany them.

The child who pays attention to it for the first time is overwhelmed by this carol because it confirms the painful revelation of the fact of death, which usually comes to him with such unnecessary precocity around the age of four or five.

Things will not always remain the same as they are now, in the timeless arcadia of the childish present.

The parents will grow old and die, just like the family dog or cat will die, and incredible as it may seem, oneself will also die, and we will never come back.

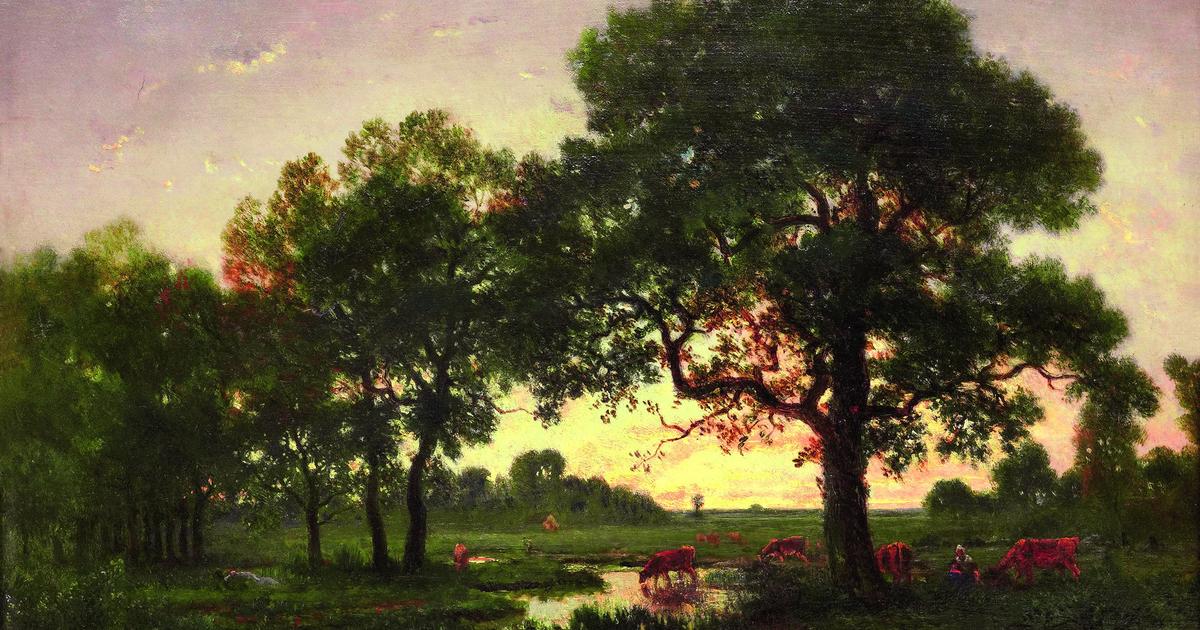

Béla Bartók summarizes in three the decisive features of popular music: formal nakedness, expressive intensity, absence of sentimentality.

Now Christmas carols are usually a high-pitched, sugary-voiced ditty playing in the background of a shopping mall, but the ones that were still being sung when I was a child could enunciate truths as bitter as the one in that verse that Cyril Connolly loved, and they corresponded exactly with the features that Béla Bartók defined, which are more or less the same ones that attracted the two great Spanish inquirers of popular music, Manuel de Falla and Federico García Lorca.

I woke up one morning in December and knew that Easter was beginning, as they said then,

In them, the devotional content was almost non-existent, beyond the proclamation of joy for the newborn, in which all the jubilation and earthly amazement was encrypted for that unusual fact that is the birth of a creature.

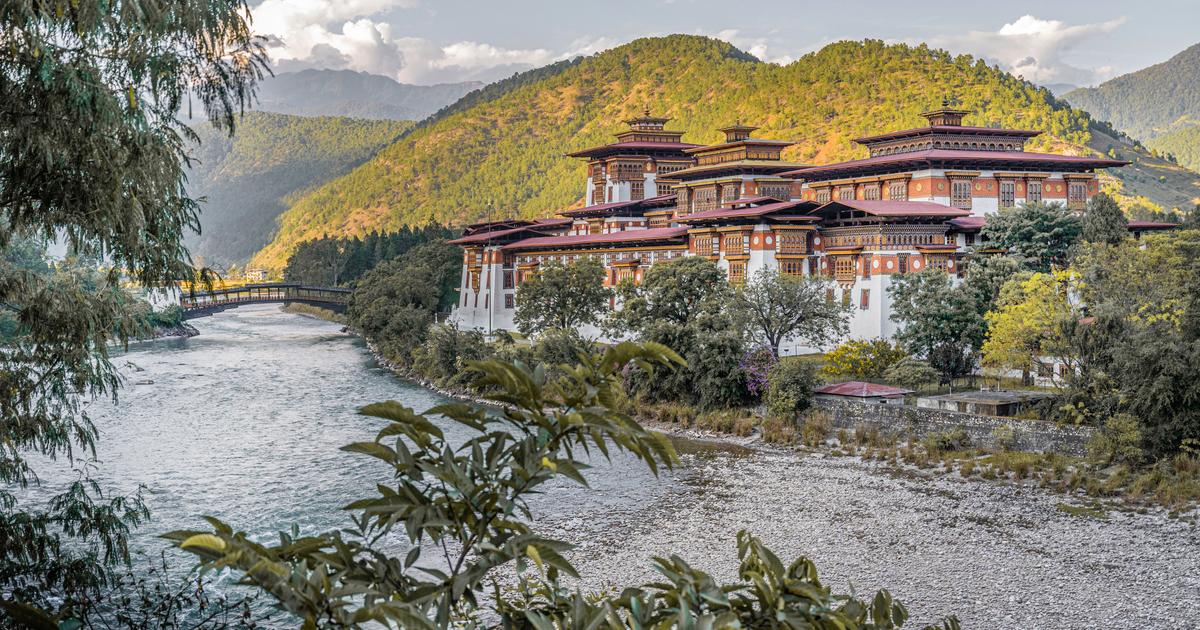

What seduced me about those Christmas carols were their stories of weather and homelessness, and a wealth of details about popular life very similar to that found in Neapolitan nativity scenes, in late-medieval and Renaissance painting, and in those

presepia.

or 18th century Portuguese nativity scenes that are like visual encyclopedias and precise documents on the trades, devotions and festivals of working people, peasants and shepherds who are the first to receive the good news of the birth of Christ.

There was a Christmas carol about the Flight into Egypt in which the child cried for thirst: "Don't ask for water, my child / don't ask for water, my love / because the rivers go down cloudy / and you can't drink it."

There was another in which the baby Jesus appeared frozen and naked at the door of a house, and a charitable woman decided to welcome him: "Well, tell him to come in / and he will warm himself / because on this earth / there is no longer charity."

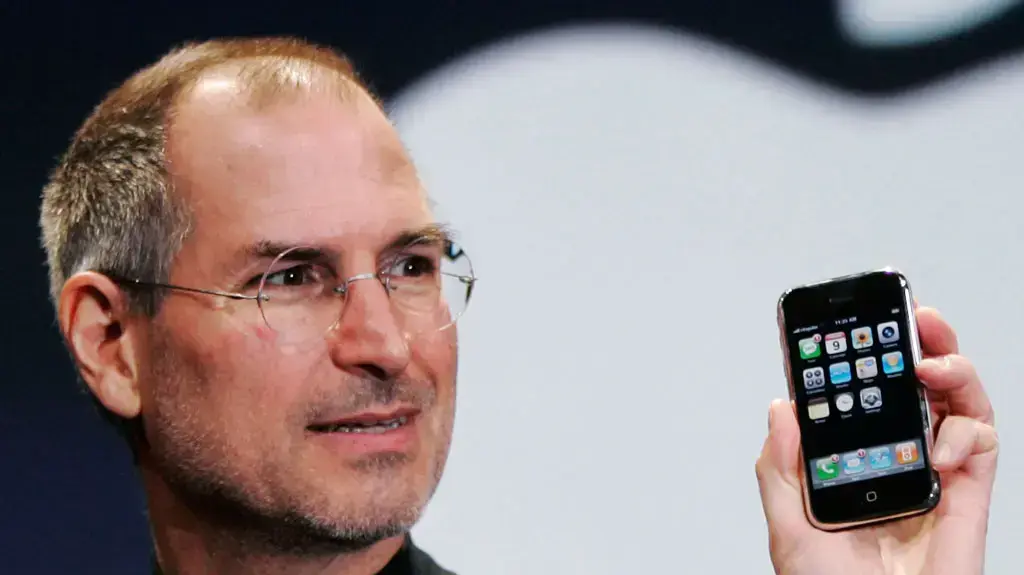

Again, they are tremendous words, which contrast with the sweetness of the intonation and the melody, and for this reason they are heard at the end of the most bitter Christmas fable in cinema, Luis G. Berlanga's

Plácido

, where a note is added about the charity that the women in my house also sometimes sang: “And there never has been / and there never will be”.

in

placido

, while the people of order show off displaying the self-righteousness of their petty charities, a helpless family goes from one place to another asking for help that nobody gives them, as vagabond on their poor motorcycle as José and María in the evangelical tale, the carpenter without work and the very young pregnant woman about to give birth who cannot find a shelter where she can spend the night and where she may have to give birth.

Listening to the Christmas carols in the warmth and safety of his home, in the shelter of his family, the boy sensed the fear of uprooting, the unexplained cruelty of a world in which there were people without a roof to protect them on frosty nights. of those Decembers

After many years and a lot of disbelief, I realize that perhaps it was in the Christmas carols and popular arts that many of us were transmitted the first notions about goodness and justice, about the radical border between protected and expelled, among the powerful who ride in processions loaded with treasures and the poor who bring to the portal of Bethlehem the valuable offering of a basket of eggs, or cheese, or a chicken.

In the background of some paintings of the Nativity, and of some

presepios

Portuguese, terrible scenes of the Massacre of the Innocents are seen.

The same wandering couple who found no shelter in Bethlehem have to flee to another country with their newborn son to escape the pursuit of a homicidal despot.

Vladimir Putin bombing schools and maternity hospitals is one of Herod's variable names.

There are fables that last forever because they contain a contemporary core of truth.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber