On May 6, 1959, when she had been in labor for 20 hours, young Elia Pérez made her husband, Julio Otero, a trumpeter with the American Circus, promise that they would never have another child.

That pain would happen only once in her life.

He promised her.

Thus, her desire to have a son was playing a single card.

“Many years later, she confessed to me that she got the biggest upset of her life when she saw me,” says Julia Otero (A Penela, Monforte, 63 years old).

"And later, when I got pregnant, she told me, 'I just hope you're as lucky as me, and she's a girl.'

When Julia was three years old, her father emigrated to the Poble Sec neighborhood of Barcelona to look for work (he found it as an electrical appliance salesman) and, a few days later, her mother took the girl to Catalonia on a train in which she was traveling a company of comedians, with wooden seats, on a 28-hour trip in which she cried all the time saying: "I want to go back with my avoíña"

["I want to go back to my granny"].

They left behind the house in the Galician village of their grandfather, a stonemason, where they put the pigs and cows to sleep on the ground floor so that, among other things, they would give heat to the upper part.

That house has been rebuilt by Julia Otero, presenter of

Julia on the wave

(Onda Cero) and

Días de Tele

on La1 on RTVE, produced by Lacoproductora, from Grupo PRISA, editor of EL PAÍS, which opens this Tuesday.

Otero finds herself these days doing everything she swore she would never do again when she began chemotherapy for colon cancer, for which she has to undergo a review every three months.

The interview, planned to talk about journalism and politics, ends up being about more urgent and far-reaching issues: life and death.

Question.

She left Galicia at the age of three.

Reply.

But I learned to love it in Catalonia.

See the love they feel here for the language, the culture, the land.

All of this told me that I also had to respect my mother tongue, the place where I was born, the idiosyncrasy of the people.

The more deeply I have known Catalonia, the more Galician I have become.

Q.

Why?

R.

Because we share something that, if we don't defend it, no one else will.

There are even people who attack that diversity;

luckily I don't know anyone interesting who thinks like that.

Q.

Social networks.

R.

The most dangerous are those who aspire to purity.

We are a bag of defects and contradictions: let people make mistakes.

We are undergoing a purity ITV daily, as if prestige were a house of cards built very slowly until, with a little breeze, everything falls apart.

It's scary.

Unless you're so strong you don't care, but I don't know of anyone like that.

On the contrary: older people are more afraid of saying something inconvenient, of screwing up, of risking an opinion.

And everything becomes pointless.

If you can't express what you think because you're worried about the reaction, you end up talking about the sex of angels.

Q.

You have been an interviewer for almost always.

R.

Doing interviews makes you the least mythomaniac in the world: you realize in front of anyone that that person is exactly the same as you.

The interviewee is made of the same fears, the same insecurities, the same uncertainties as you.

And he is trying to impress you, seduce you and look good like you would if you were on the other side.

P.

You say that now everything matters a little less to you.

R.

It happens when you are about to die, or with the prospect of dying, because they keep checking me every three months.

If they find a metastasis, maybe I have two years left, or less.

Q.

Cancer.

R.

Our cells that go crazy, selfish and immortal because they reproduce with unusual speed.

And they also become travelers: they know that, sooner or later, the immune system can locate them and go after them.

Q.

Do you travel?

R.

A cancer cell, the bravest of all, takes a ship - the bloodstream - as if it were a conqueror going to America, and looks for another place to colonize.

That traveling cell is the one that they look for me every three months.

The mother of metastasis.

If a single cell manages to prevail over the storm and evade all controls (the bloodstream in which the immune system works to neutralize it, the white blood cells, the defense system of our biology) and settles in another organ, that is a supercell. of such caliber, of such malignancy, that it is very difficult for anything to defeat it.

That is why metastasis is the most dangerous part of cancer.

It is the cancer that has traveled.

For a cell of that size, going from the intestine to the lung is a true epic.

Q.

How long will your quarterly checkups take?

R.

They will be looking for me for five years if any traveling cell has reached port.

Imagine what feeling of living I am with.

Carpe Diem.

Q.

What is

carpe diem

like in a cancer patient?

R.

Forgetting that after three months you have to get into the CT tube.

Three months: three fucking months.

But I'm letting myself down.

Q.

Why?

A.

Because at the beginning, when the tumor was large and there was no certainty that we could deal with it, I believed that if it came out, it would come out differently.

I would be brave to do things I haven't done, and brave not to do what I didn't want to do.

And I'm doing everything I swore I wouldn't do, working harder than I did before I was diagnosed.

Eternal days, which is not good for my health either: you have to pamper your immune system, eat well, respect the hours of rest and sleep.

Q.

And go back to television.

A.

For the challenge.

Do you still feel good on a set?

Can you still organize it?

A move with 200 people in the public.

Six or seven guests.

Four or five collaborators.

It's putting a test on myself.

And it may be the last letter I have to do TV.

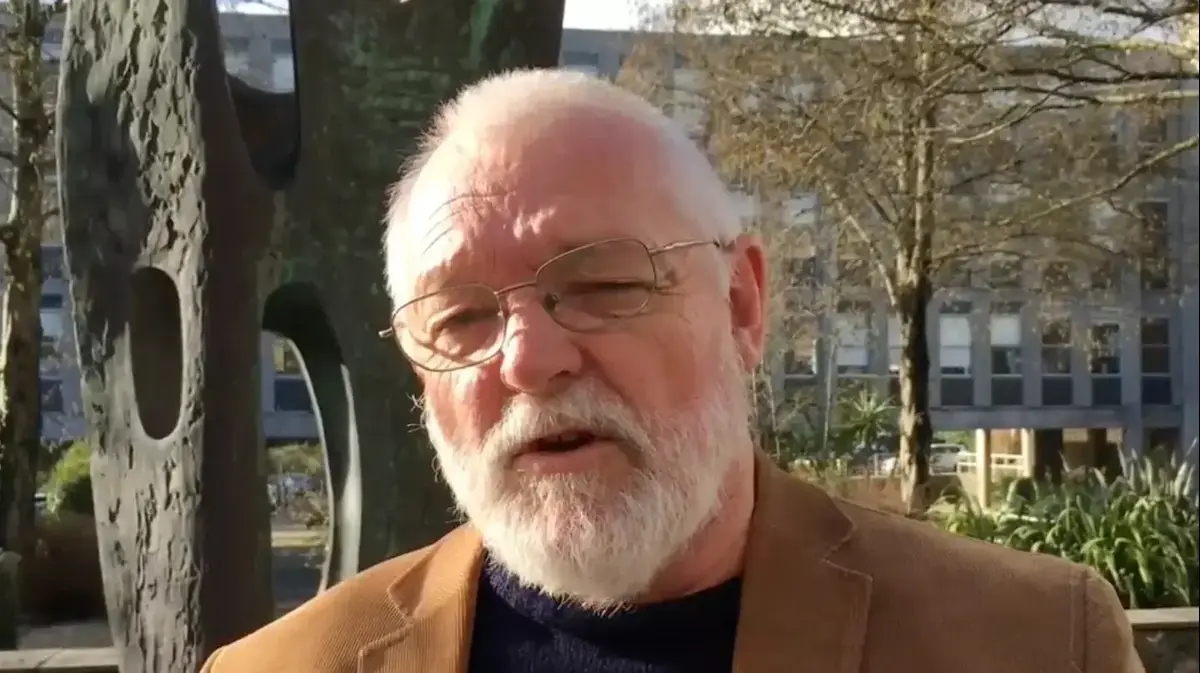

Julia Otero receives the Ondas Award for the Best Radio Career in 2013.Gianluca Battista

Q.

At the age of 27, he presents the debate program

A particular story

.

At 28, the 3x4

contest

became famous throughout Spain.

At 29, the talk show

La Luna

through which Anthony Quinn, Alfonso Guerra, Gutiérrez Mellado, Tina Turner, Lola Flores or Mario Conde pass.

R.

I am comfortable in there.

It has no merit, it is a gift.

You either have or you don't have the ability to address a camera normally, you can't learn it.

And no one can boast of that, because it is innate.

It's like bragging about drawing well.

I am unable to draw a house.

Q.

How do you live without 40 centimeters of intestine?

R.

There is not a single centimeter free in our body.

If we have it, it's for a reason.

My gastrointestinal system is not the same as that of a normal person.

Transits are much faster, for example.

I am careful with the amounts I eat, always very little.

When you are away from home for many hours, you have to ensure that the diet favors slow digestion, never fast.

Organize my working hours according to my needs;

I try to eat early, and eat fiber.

Take the right protein, the right carbohydrates, the vitamin.

Q.

Chemotherapy.

A.

Controlled poison.

A dose of poison that kills a lot.

It kills everything bad and also takes many of the good things, and you have to try not to kill you.

The good oncologist is the one who seeks the limit of the patient.

The more he punishes you without killing you, the better.

If we get out of hand, we've screwed ourselves, but hey.

You have to find the limit.

Anything the patient can take will be better than staying a degree early.

Q.

The question is to know what that degree is.

R.

When I started I knew that colon cancer is nine cycles of chemo.

I asked: "Why nine?"

And I instantly realized: "Don't tell me: because the one who had 10 was killed, and the one who had eight was reproduced."

We are there.

Q.

It endured the nine cycles.

R.

And I reached a point where I didn't care if I was alive or dead.

Everyone talks about tiredness: it's worse.

The breath of life leaves you.

Chemotherapy can lead to the feeling that being alive or dead doesn't seem very different to you.

Q

...

R.

The toxicity of chemotherapy is cumulative.

The eighth cycle is not the second.

You see how you are deteriorating, how the sores are coming out.

Suddenly your nose bleeds, your tongue bleeds, you have a sore in your mouth.

All intestinal transit is raw.

And you feel that indifference to life.

If they tell you "you press that button and you die", you think "well, nothing happens either".

Mind you, it also depends on the circumstances.

If it happens to you at 30 years old and you have small children, it must be a different emotional situation than if you are 60 and have a daughter already raised.

The only thing that hurt me was my mother, who is still alive, and a mother should never bury a child.

But yes: you reach a state in which life is not so important.

And you see those who cling to it, who are perfectly healthy and see what is happening to you as a tragedy,

with a certain mercy, as if they didn't know they were going to die too.

The younger, the less.

They have not yet discovered that we have an expiration date and that being alive or being dead can depend on a moment.

Julia Otero with the writer Antonio Gala, in Madrid in 1995. Gianni Ferrari (Getty Images)

Q.

How do you sleep during chemotherapy?

R.

With trankimazín the hardest days.

Sleeping and not thinking is good.

You have to manage everything with energy and hope, because when you are recovering from one cycle comes the next.

If the oncologist tells you to walk eight kilometers every day even if you are half dead, you have to walk those kilometers to recover your neutrophils.

Because if you reach 800 neutrophils instead of the 2,000 that you have to have, you have to suspend the next cycle, postpone it.

I was very obedient in everything they told me, I complied with everything.

He took excellent care of me.

And all this, with the feeling that if I left, I wouldn't care so much.

I know it's weird.

It is not easy to tell, nor easy to understand.

Q.

"For an inexplicable reason of pain, beauty and the determination to exist", sings Iván Ferreiro.

You don't know anything about yourself when you reach the limit.

R.

The level of resistance and suffering that we are capable of assuming is very high.

And I think almost all of us do.

The more pain and suffering, the more the ability to resist increases.

The fact that you are a complainer with a fever of 38 does not mean that you cannot withstand an extreme situation of serious illness with aggressive treatment.

At the end of it all you find a person inside you that you didn't know existed.

Q.

You recommended a book to María Escario [the journalist has announced that she has breast cancer].

R.

I recommend it to many people, the last of them, María Escario.

Selfish, immortal and travelers

(Planeta, 2021) by Carlos López Otín.

When she finished reading it, he told me: "It's just that I even see the poetics of cancer."

Well, is that biology is pure poetry.

When you are inside your body, and you know exactly what is happening, what substance is entering your subclavian, where it is going and what is causing it.

There is a poetics of biology.

Even the cancer cell has its epic: how it tries to escape from where it is, to find a new way to see if it can survive.

A crazy cell, an aberrant cell, literally called that.

Everything he does in his environment, what he achieves.

And all that happens inside our body has an impressive transfer to society.

Q.

How?

R.

Society works when there is altruism.

And the body too.

There is that way of seeing the world within us.

Cells help each other to locate the one that is harming us.

The one that thinks it's not right gets out of the way, that's called apoptosis: it kills itself.

How are they protected?

It is of an altruism and an amazing generosity.

All of this in the face of the cancer cell that does the opposite: it tastes bad, "I'm not the same as the cell I came from, and now a guy is going to come along who is going to destroy me because I don't do my job well, I'm going to see how I can fool him."

And it starts fooling the whole body: the immune system, the antibodies, everything.

He begins to create his own circulatory system.

That's where the word cancer comes from: cancer is crab.

Where there is a cancerous tumor there is a kind of crab legs, which are the circulatory endings that the tumor creates to supply itself with blood.

And start to go free.

She doesn't give a damn about hurting everyone else: that cell is in her interest, to maintain herself.

You transfer that to the social body and it is the same.

Selfishness kills the best.

Of the social body and the biological body.

Julia Otero interviews Joan Manuel Serrat and Joaquín Sabina in the TVE program 'Interview a la carte', in 2012.

Q.

He told

El Hormiguero

that he came to ask his cells for forgiveness.

R.

[Smiles] Good ones.

It gave encouragement to my good cells so that they resist the aggression to which I subjected them.

And yes, I apologized.

I was in the box, about to start a cycle of chemo, and I was thinking that there are millions of cells that are going to die in order to save me.

Just for sinners.

But there is another poetry.

Q.

Which one?

A.

Good cells, those that do not die from aggression, as they are mature and competent cells, know how to repair themselves.

Instead, a cancer cell doesn't know where to start and dies.

The bad ones die, the good ones find their way to recovery.

Q.

You are informed.

R.

The information for me was a lifeline.

You become aware of your body.

Now why do I get sores in my mouth?

Why do I have this pain here?

Why does my hair fall out?

Knowing everything at all times helped me.

There are people who choose not to know;

people who are given a sealed envelope when they leave the CT and give it to the oncologist.

I do not.

Everyone has their strategy.

Q.

Did you come to think that very human thing of "how will they remember me"?

A.

It was not necessary.

When I was diagnosed I already lived my funeral.

When I made it public, specifically.

And the reaction that there was, what I found in the media and on social networks (although there were three or four who said "I hope he dies", but who cares about those people) gave me an idea of what would be said if I I would have died.

My disappearance was a way of living in life.

It was, within the macabre, very nice to read what I read.

It won't be much different when it happens.

Q.

In many years.

R.

They will not be so many.

I'm missing my spleen, I'm missing my gallbladder, I'm missing my thyroid, I'm missing 40 centimeters of intestine.

I lack everything!

[Laughs] I have four essential things left, and with that I shoot.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/CAHSVQLJ3BG67CVS2AKJQBHDCM.JPG)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/KMEYMJKESBAZBE4MRBAM4TGHIQ.jpg)