"Perhaps the lesser evil always wins. I see the elections in the

United States, France, Brazil

and I think that in the last ones, with

Biden, Macron, Lula

, the lesser evil won. Perhaps that is the way things are and this in itself would not seem so strange," says democracy expert, Polish-American political scientist

Adam Przeworski

pragmatically , shortly after landing in Buenos Aires to where he came to spend his vacation in the countryside with friends. He arrived from

South Korea

, where he gave a lecture on democracy before an audience of a million people!

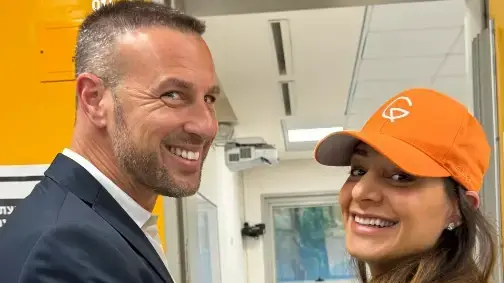

Adam Przeworski, professor of Political Science and one of the main theorists and analysts of topics related to democracy and political economy. Photo: María Eugenia Cerutti

The news coming from the Latin American neighbors is alarming.

After the coup attempt in

Brazil

, on Monday, January 16, a judge of

the Superior Electoral Tribunal

(TSE) demanded explanations from former Brazilian President

Jair Bolsonaro

about the draft of a decree that established a state of national emergency that annulled the October elections that he won.

Lula da Silva and that

Court

intervened

.

We are learning more details of the conspiracy.

Meanwhile, in Peru we are witnessing deep frustration with the young democracy, which has failed to resolve the huge gap between rich and poor and between Lima and the country's rural areas, for example.

Democracies go through crises – the erosion of institutions, the rise of extreme parties, polarization – and it is not necessarily strange, but rather commonplace: no democratic system works ideally.

Przeworski

dedicated his academic life to the study of democracies, in 2022 his book

Las crises de la democracia

(Siglo XXI) was translated from him and he was interviewed by

Ñ

about it.

This week he analyzed the present of the democratic systems of

Argentina, Brazil, Peru

and

the United States

.

“When I look at the situation in Argentina, I see several crises, inflation, an increase in poverty, perhaps a bit of polarization, but I don't think there is a crisis of democracy.

Democracy in Argentina is going the way it is: there are ugly things, conflicts, but the institutions are very strong and the support is very strong”, he declared as soon as the conversation began.

Ricardo Darín and Peter Lanzani in "Argentina 1985". Photo: EFE/ A Contracorriente Films

–Did you see the movie

Argentina 1985

?

-Yes.

As a film it's not very good, but it reminded me of many moments when I frequented this country.

I participated in a large project on

Human Rights

together with

Carlos Acuña

and

Luis Moreno Ocampo

.

We have written a book, I lived these events day by day.

I realized, watching the movie, how dangerous those intense moments were.

We were full of optimism and resolve, we wanted to solve the problem of political violence once and for all and perhaps it would be a great success: the fact that the military could be prosecuted and put in jail was unprecedented, and it lives on.

And I'm glad about the film because I think its effect should be a revitalization of

democratic attitudes

.

– What do you think of the current attempt by the national government to bring the Court to impeachment?

-I do not like it.

When the Executive moves against the courts, it is extremely dangerous.

Democracy is a system in which we manage social, political, and economic

conflicts

within an institutional framework that we take as given.

If the parties to the conflict are the institutions, the conflict escalates and becomes dangerous.

But crises are the daily life of our society, and of politics.

– You always talk about the “intensification of everyday life”. I think of György Lukács and what a time to be alive! What can you say about these intensifications?

This is how the buildings of Brasilia were after the Bolsonaro attack. Photo: CARL DE SOUZA / AFP

–I think there is something new, that the situations are different.

In some countries there is a strong crystallization of political divisions, an unconditional polarization.

That is, people are divided between those who support one political force and others who support another political force without conditions, regardless of what these forces do in government.

In Brazil, those of the PT

(Partido de los Trabajadores

) support the PT, the anti-PT oppose the PT, and it doesn't really matter what the government does or what Bolsonaro did in government.

The same in the US In other countries, the situation is different because what happened – and this is particularly true in several European countries – is that there is a political breakdown.

The traditional center-left and center-right parties lost a lot of support, the center lost support, new parties appear, there are no dominant parties that win re-election and remain in government – like the

Christian Democracy

in

Italy

–, the political system is divided into little pieces and the situation is difficult because it is difficult to create coalitions that can govern.

But they are different phenomena.

The danger of polarization in recent years is exactly what we have seen in the

US

, in

Brazil

, and it is that the government loses the elections and does not recognize the loss.

This is new and very dangerous.

The most important thing for it to work, for a democracy to survive, is that we all know how to lose.

As I said many years ago, democracy is a system in which parties lose elections, which is very unpleasant, it hurts, but for democracy to work we need to recognize that we can lose, to accept the loss.

I also want to say that the government that enters, the one that wins, does not repress, does not hinder the chances of the opposition winning the next election, listening to the opposition, etc.

But this ability to accept losses is essential to me.

What happened in

the United States

it was totally surprising to me.

The country had 22 instances in the last two hundred or so years in which the parties that controlled the presidency lost elections and accepted the result, except for one in 1886. Then one would have thought that it was already in the DNA, in the genetics of this democracy, and suddenly Mr.

Trump

appeared .

And now... Brazil.

–The situation in Brazil has changed since the last time we spoke (July 2022). The vote for Lula was the opposite of the one Bolsonaro obtained: it is not a hopeless or angry vote. How do you see this change of government?

Lula and former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso (.Photo: Ricardo STUCKER / AFP

Bolsonaro lost.

According to the agreement that

Fernando Henrique Cardoso

made with

Lula

, the transition of the government was institutionalized.

There are rules now regulating how the transition should be and the loser must honor these rules, drop any pretenses of winning, and may even continue as head of the opposition.

But once again we have entered a crisis, which I don't think is over because the danger is still there.

The situation in Brazil seems to me even more dangerous than in the US, because it seems that in

Brazil

the security apparatus, the army, the various types of police, are divided.

Before the 2020 election, there were rumors about the position and political attitudes of various US armed forces. One thought, what would the presidential guard have done if Trump said “no, no, no, I want to be president” ?

Who would they have supported?

There were rumors, statements from police groups, political statements, something that had never happened before.

At that time, I wrote that there was a smell of

Latin America

in the 1960s or 1970s. But in Brazil these divisions are real and one does not know what roots they have, how deep the roots of those divisions are.

Lula

's government

They are in a difficult situation because on the one hand, they do have to control the situation, they have to punish, but on the other, they cannot repress much.

And the constitutional courts are playing a very active role and the legitimacy of this intervention is not obvious.

– Do you think that the future of the Brazilian government in this context is neither stable nor hopeful?

I'm afraid not, although Lula has a lot of political skill and has respect for institutions.

–He also has experience and a political past.

–Yes, he has a very good political nose, experience, respect for the institutions, good people around him, but he is facing a very difficult situation because touching the Military Police, the military is difficult.

In 2020 Trump received Bolsonaro in Palm Beach, Florida. Photo: REUTERS / Tom Brenner

–You thought that characters like Trump and Bolsonaro were going to disappear quickly. What do you think now?

–What I learned with Trump and with Bolsonaro, is that they created a social force and a political force, that in Brazil there is a phenomenon that can be called Bolsonaro that does not depend so much on the character.

And in the US,

Trump

is finished and he will no longer have a dominant role in politics, but Trumpism has very solid roots in society and in political force.

And the same thing happens with Bolsonarismo.

Bolsonaro

lost, but many of his followers won governorships and seats in congress, he is a force.

Is there democracy possible in Peru? I think of the hatred shown by political positions, the rapid destabilization of traditional party systems, the institutional deterioration, but nothing is new.

–Polarization exists in several countries.

There is an institutional structure that, with the problems and everything, ends up managing these conflicts.

If democracy is a system in which we can manage conflicts by applying institutional rules, etc., Peru does not manage to do so.

And I don't know exactly why, but it is very easy to remove a president in

Peru

.

There are elections, someone wins by the rules, and immediately

Congress

begins to impeach him.

I think that there is something in that institutional system that is not working, not only the social situation, the ethnic and economic conflicts, there is an institutional weakness.

Dina Boluarte, the Peruvian president elected by Congress after the ouster of Pedro Castillo, faces massive protests across the country. Photo: Melina Mejia / AFP

Can we think of Montesquieu?

I don't think it's Montesquieu, I think maybe it's something more particular and it's this relationship that it's not clear if Peru is a presidential or parliamentary system.

In a presidential system, there are elections, someone is elected and ends his term, unless he commits crimes, and in Peru the system is formally presidential, but it appears parliamentary.

Every time a president is elected, he loses the trust of

Congress

and leaves.

And the recall qualification is extremely vague.

Adam Przeworski maintains that "In some countries there is a strong crystallization of political divisions, an unconditional polarization". Photo: María Eugenia Cerutti

–Democracy has reaped situations of inequality, internal and external enemies. Does the current democracy disappoint?

-Yes.

I'm going to sing a bit of my usual song:

democracy always disappoints

.

It is in their nature, the candidates generate hope in the elections and then we are disappointed.

I once wrote that almost 50% of the voters are on the losing end, so he is disappointed.

Then half of those who voted for the winning candidate are disappointed with his performance.

So

most are always disappointed

.

But what are you waiting for?

May your candidate, your party, win in the next election and not be disappointed.

And this happens election after election, the disappointment is in the nature of democracy.

This oscillation between hope and disappointment seems normal to me.

Yes, there are many more cases where it seems that the democratic systems that functioned for decades – India 60, 70 years ago – are weakening, perhaps destroying, a process that people call

backsliding.

.

But there is also more democracy, I am not sure if it is more as a proportion, but in numbers there is more.

And yes, there are countries in which one hoped that this would not happen.

India, a poor country that had a very strong democratic system that worked very well and suddenly now I don't know if we can still talk about democracy in India.

And it is something very ugly because it has these

religious, ethnic bases

that make the situation extremely repressive.

There are big disappointments, but I don't know if there are more now than before.

And I don't believe much in the pollsters' question that proposes: “Is democracy the best form of government?”.

There are no alternatives to democracy either...

-Either.

What is new and perhaps something that should encourage our optimism is that there is no ideology in the world that could serve as an alternative model.

Does not exist.

And everyone – I don't like it – speaks a

very democratic

language .

The

extreme right

in Europe is not anti-democratic, it talks about democracy all the time.

What would be an example of current high-quality democracy?

Democracy works well in Spain, Germany, it improved in

Kenya

, it works well in

Ghana

, in

South Korea

and it works quite well in Argentina.

I don't like the Supreme Court, but it works quite well in Argentina.

– Does the fact that it works mean that it is of high quality?

Crises of Democracy, by Adam Przeworski.

XXI Century Editorial.

–High quality… this topic opens up another point, which is the impact of

money

on politics.

Even in countries where democracy works very well, it seems that it does not have the expected effect, that of reducing inequality.

It seems that our

representative systems

are compatible with a high degree of inequality.

And if we had had true political equality, that is, a situation in which all citizens had the same weight of influence over politics, I don't think we would have had such inequality.

What happens is that in economically and socially

unequal societies

there is no political equality, and money through various channels seeps into political decision-making and perpetuates economic inequality.

In countries where unions were strongly centralized, they could function as a counterbalance to the impact of big business.

That was the reason why the Scandinavian countries had a more equal distribution of income than other countries.

But

unions

no longer work this way.

There are attempts to legally regulate the flow of money into politics, but it is very difficult because large companies have great capacity.

look too

Andrés Malamud: "Trying to judge the Court is a smokescreen"

Brazil.

Mass advocacy for rights