At mid-morning on a summer Monday, Alia Trabucco Zerán (Santiago de Chile, 1983) should probably have been in any office of the Judiciary as a lawyer for a human rights case.

Investigating, litigating, preparing briefs.

But the Chilean decided a few years ago to double her destiny upon finishing Law School and send the devil “the language of the law”, as she calls it, which she describes as “harsh, hierarchical and, above all, armored ”.

She first started off as a side quest and then the trail became apparent.

“The contrast began to anguish me: happiness when I sat down to write fiction, unhappiness when it was a quarrel;

the anguish when going to court, the joy of the workshop”.

Literature was his antidote.

She tells it in a cafeteria that has nothing to do with the Chilean courts: spacious, bright and colorful.

It is the area where Trabucco lives, in the municipality of Ñuñoa, in Santiago de Chile, one of the places in the capital where neighborhood life is still breathed, although modern buildings now occupy the place of mansions from the mid-20th century. .

Small business, children in the square taking advantage of the holidays, people on bicycles, discreet restaurants, lifelong neighbors.

Shortly before, upon entering Filomena —this is the name of the cafeteria where he has summoned us—, Trabucco is seen smiling and walking briskly, although he arrives very punctually.

He hugs warmly to say hello, he will just ask for a bottle of sparkling water and what will come will be a friendly and pleasant chat,

Limpia

, which is published in Spain on January 26.

“That it is an uncomfortable novel.

For me that is a great compliment”, says one of the most forceful voices of current Chilean literature.

“Sometimes it happens to me that I feel closer to the previous generation, the one that was born in the seventies”

Author of the novel

La subtraction

and the essay

Las homicidas,

for which she won the British Academy Book Prize in 2022 for understanding between cultures, in

Limpia

“uncomfortably” addresses the life of a housekeeper and the seven years she spends working for an upper-class family in Santiago, Chile.

A forty-something couple swamped with work, certainly unhappy, whose little daughter will die, as announced in the first lines of the book.

Deliciously distressing, addictive, the novel portrays everyday worlds that can become a storm for the weak.

“The class contrast that is portrayed in the novel is not exclusive to Chile, but it is certainly very present here.

Studies have been circulating for decades indicating that my country has one of the worst distributions of wealth in the region.

And that creates abysses.

The story of

Clean

Somehow, it narrates that abyss from a particular perspective, that of the protagonist, Estela”.

The worker's narration questions constantly.

“Unlike other literary voices of popular characters, her voice stumbles the reader.

Can a private house worker use those words or is it implausible?

And who determines which words are appropriate or inappropriate?

Those questions, more reflective, are somehow in the novel”, says Trabucco about a book that took four years to write and that, as in the rest of his work, there is a profoundly political look (and not only because on the pages In the end, images of the Chilean social outbreak of 2019 appear, a milestone that has definitively marked Chile and its future).

Trabucco does not believe in the categories of people born at the same time (“sometimes it happens to me that I feel a greater biographical closeness with the previous generation, those born in the seventies”), but he is part of those born in the early years of the decade of the eighties, in the Pinochet dictatorship.

People who manage to keep memories of that dark time and keep marks that will not dissolve with the passage of time.

He tries to slip away when asked about episodes in his life that help to understand his work, because he thinks that it is "the sum of gestures and words that ends up having an impact in unexpected ways."

Until, finally, he answers: “Being born under a dictatorship and being the daughter of parents who suffered its consequences —my father in his own body,

having been imprisoned and tortured — left me with a wound or perhaps inflicted a wound on my imagination.

And that wound remained, as a threat that at any moment there is an abyss, a fall, a cold, and from there I think a restlessness comes that leads me towards certain materials in writing”.

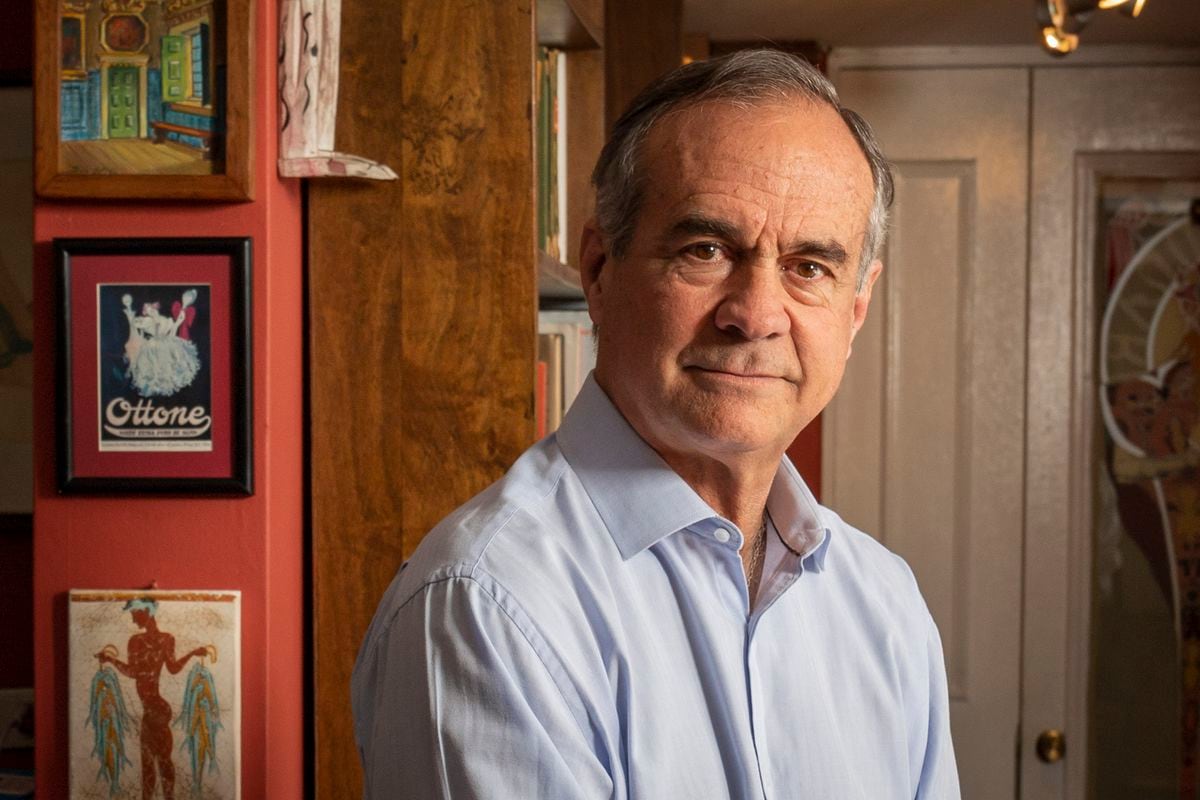

The writer Alia Trabucco, at her home in Santiago.

CRISTOBAL VENEGAS

She is the daughter of a well-known Chilean couple of left-wing intellectuals: Sergio Trabucco, a filmmaker, and Faride Zerán, a journalist.

Hers was a confusing childhood —as childhood usually is, she reflects—, “but with the added bonus of being aware, very early, of the existence of an overwhelming violence that was there, latent.

It is something that marks you, of course, at a time where innocence supposedly prevails, ”she recalls about the regime.

It was the time when childhood fantasies led her to become a human rights lawyer as an adult, to take Pinochet to the bench, but where her refuge was in letters.

The author says that she was "fortunate" that books were part of her life from childhood and that, later, writing appeared as a game, "like something similar to drawing."

"One letter next to another,

try colors, put together a word, little more than that”.

Secret life diaries that were once discovered by a cousin of hers who makes fun of her and that make her understand that writing is a fundamental part of her life at the age of 10.

Then she, as an adult, she has turned to journals when she feels "downright lost or confused or overwhelmed."

This conversation, Trabucco confesses, has made him think about private life and work.

He does not like social networks nor does he like the exhibition, because he prefers to protect his privacy.

It is considered reserved, even somewhat shy in certain spaces.

But, above all, she prefers to speak through her works, "so that the books are read as such and that the author does not have to be pushing them or explaining them madly."

Deep down, a vital concern in a successful literary career, which she has just begun: "I don't want to lose freedom in my writing or let anything condition it," says the author.

“I never feel with a pedagogical intention to write.

Fiction works in cracks, in gray areas”

She acknowledges the influence of her compatriot Lina Meruane, her friend and professor in the Master's in Creative Writing at New York University, who supported her while she wrote her first novel.

“Her prose of hers has an incredible rhythm, she is very lucid and unexpected,” she says of the author of

Sangre en el ojo.

He names the Chileans Carlos Droguett, Manuel Rojas, Diamela Eltit, and theoretical authors such as Julieta Kirkwood and Nelly Richard.

To Herta Müller (“I like it for the challenge and because the work that reading gives derives in enormous pleasure: a wonderful sentence or a deep idea, sometimes more philosophical or lyrical, that leaves its mark”), to Maggie Nelson ( "I like that freedom to write what he wants and I feel quite identified with that") and Kafka, Faulkner and Woolf, to whom he always returns.

She says that she learns from other Latin American writers: "Sara Gallardo has been a find and I follow magnificent contemporaries like Cristina Rivera Garza and Fernanda Melchor with great admiration."

After Law School and "feeding the spirit with sawdust, as Kafka said," she began working as a human rights lawyer, taking cases of political violence in other countries and in Chile, but emotionally she couldn't stand it.

“It caused me enormous pain, an indignation that clouded me.

He wasn't the right person.

So at that moment I took refuge in reading.

She read frantically, slept little;

each book was a discovery and took me further away from that pain of the world of law”.

In that stage as a young lawyer, she worked for sexual diversity and feminism, while participating in literary workshops with writers such as the Chilean Alejandra Costamagna, with whom she took a short story course.

Feminism explains, in part, the critical thought that is present in Trabucco's gaze.

In his non-fiction book

Las homicidas,

where he deals with symbolic cases of murderous women, "the question of the laws of the genre is central, although in the case of fiction things are more oblique."

In his first novel,

La subtracta,

"there is not a single heterosexual character and the forms of community are woven outside the family order and blood."

This aspect, says the writer, "which has been erased in many of the readings that were done in Chile, allows us to trace less explored subjectivities around desire and

queerness ."

”.

“Is there feminism there?” she asks herself.

“I don't know and I don't care,” she replies.

“It is something that others may or may not observe later, but I never feel with a pedagogical intention to write nor is it something that guides me because fiction works in cracks, in gray areas”.

Detail of the bookstore in the house of the feminist writer Alia Trabucco, of Chilean nationality.

Photography: CRISTÓBAL VENEGASCRISTÓBAL VENEGAS

In his work there is freedom and experimentation.

He says that a few days ago she was talking to a friend about Herta Müller and Thomas Bernhard and they agreed that they are authors whose books always have the same rhythm, a similar breath.

But she is not like that, she describes: “The three books that I have published are formally very different from each other, thematically different, they have different rhythms or melodies, affective fields that do not resemble each other.

So for me each book is a unit to explore voices, forms, structures, ideas, fiction or non-fiction, the most lyrical or the most prosaic.

The idea of work is a bit foreign to me”.

The Chilean exemplifies with a house, where she is inside it — hammering nails, painting walls, repairing cracks and then beautifying a space — but that she cannot fully see because she does not know it well and explores it a little grope.

His postgraduate degree in creative writing in New York was for Trabucco "a wonderful experience."

He later did a PhD in Latin American Studies at University College London, in a strategy to continue opening spaces for writing and thought.

"Because, for me, writing is also a key space for thought, reflection, a place from which to look at the world and feel less lost."

It was a more solitary stage and years of very relevant intellectual formation.

For the writer, her country is immersed in "a bad version of 'Back to the Future'"

In 2020 he left England and returned to Santiago de Chile, the city where he was born and where his parents, his brother, his "beloved" friends and friends live.

“It is my stage, it is where everything questions me, where I am outraged and laugh more.

I have never been homesick, but the last few years abroad were hard for me.

I wanted to go back, I needed to go back, ”says the 39-year-old writer about her return to her country, which is undergoing profound transformations.

“There is a restless and discontented Chile, chúcaro as we say around here [rebelde], stubborn, tremendously creative, explosive, funny and very beautiful.

It has manifested itself time and time again, in series of protests since 2011, and it appeared in all its complexity since 2018 with the feminist mayo and 2019 with the revolt”, says the author.

But she observes in parallel another type of country: "A fearful, authoritarian, conservative Chile,

racist and classist.

And right now, starting in 2023, that version has us back at a time of conservative restoration that is paving a rather undemocratic path, very similar to that of the early 1990s.

He envisions his country in the midst of "a bad version of

Back to the future

”, trapped in a return to the past and “not knowing how to return to the future that seemed to open up and which vanished after the defeat of the plebiscite on September 4”, where 62% of citizens rejected the proposal for a new Constitution .

It is the world of Trabucco, whose writing, he says, arises from a mixture of observation, imagination, intuition and thought, but at the same time he allows himself to be carried away by the freedom of the trade, "in putting one word next to another, in what melodic and aesthetic, where unexpected and inexplicable things happen and a spark or a detour that changes the course of a book”.

"Others already say it and I fold: if I knew what was going to happen when I started writing, I wouldn't write a single line," concludes the author.

Find it in your bookstore

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/4EINSWD6RBBIFBDILISO6X6J4Q.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/DZZ3D5N4UZGJXBRWFA7XPUJXPM.jpg)