40 years ago the scientific community and the HIV virus began an all-out war.

There are no winners, for now.

Despite the most optimistic omens of the first years, which predicted, in 1989, a vaccine against HIV "in five years", reality —and the virus— were more stubborn: not in five, not in 10, not in 30 years the vaccine has been achieved.

The contest is in a draw: the virus is still alive, but besieged;

science has failed to eliminate it, but has managed to keep it at bay with powerful antiretrovirals.

The diversity of HIV, with its immense capacity for mutation, and its extraordinary abilities to hide from the immune system, have frustrated, for now, the search for a vaccine.

Hundreds of prototypes have been studied,

but only seven have reached human efficacy trials (phase IIB or III) and none have achieved conclusive results.

The latest failed attempt has been the international MOSAICO study: a few weeks ago, the phase III trial was stopped early because the vaccine did not protect against infection.

In this kind of cat-and-mouse race, experts say, the virus is ahead.

For now.

The figures add up to the war: HIV has claimed around 40 million lives since it was first described in the 1980s and even now continues to cause 650,000 deaths and 1.5 million new cases each year in the world.

There are good treatments and the aggressive infection has become chronic, but it is not cured.

Research to prevent infection (vaccines and other strategies) has allocated at least some 19,000 million dollars between 2000 and 2019, according to calculations by the Research and Development Working Group for the Monitoring of Resources for the Prevention of Infection. HIV.

But the virus is still alive.

More information

The challenge of aging with HIV: "Long-term people suffer from depression, anxiety and cognitive decline"

First of all, HIV always has the upper hand.

Because it knows, among other things, how to neutralize the immune system from the very door of entry: when it enters the body, it integrates and hides in a type of immune cells, CD4 lymphocytes, keys to alert the immune system of the presence of strange agents.

“HIV is a virus of absolutely astonishing intelligence because it is capable of infecting and establishing itself in noble sanctuaries of our organism.

CD4 lymphocytes are memory cells that remain on alert for the rest of life [so as not to have an infection].

They don't die until I die.

If I have a virus in those cells, I will never get rid of it”, explains Josep Mallolas, head of the HIV-AIDS Unit at the Hospital Clínic in Barcelona.

The virus inserts its genetic material into the genome of CD4 cells and manipulates it so that instead of carrying out their immune function, they are dedicated to making more copies of the virus.

Thus, while it replicates and gains territory, HIV destroys CD4 cells and with it, diminishes the immune system that protects humans.

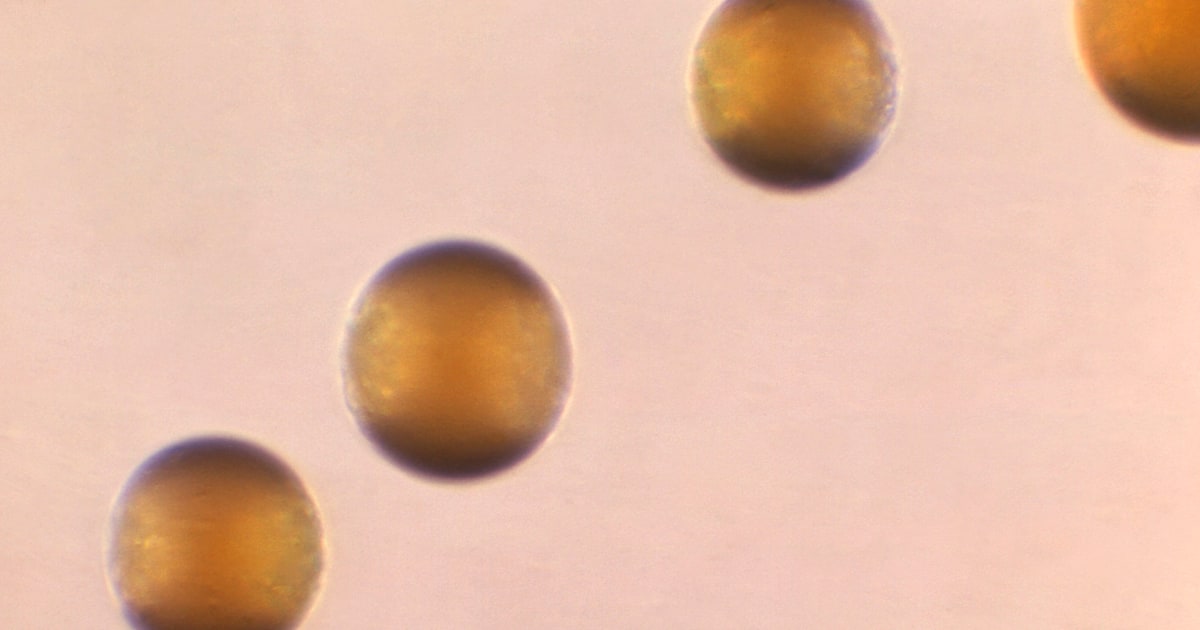

There are also some infected cells that, instead of replicating the virus, settle into a state of latency, as if asleep, and HIV can stay there, silent and hidden, in those viral reservoirs, for years.

In four decades of research, science has managed to make the infection "controllable," says Beatriz Mothe, a researcher at the Fundación Lucha contra las Infecciones.

But there are challenges ahead, such as tackling late diagnosis - a third of those infected are detected late -, avoiding new infections and, above all, developing vaccines.

“We need to arrive at a functional cure, treatments that not only control the infection [as antiretrovirals now do], but also cure it.

And we need a preventive vaccine: this is the only way to eradicate this pandemic, ”she says.

It will not be that they have not tried.

Since the mid-1980s, researchers from all over the globe have been working on it.

But without success, for now.

“The big problem is the very nature of the virus: it replicates very quickly and in the process, it spontaneously makes changes.

A sufficiently stable area of the virus has not been found [for which to target] a vaccine,” admits Vicenç Falcó, head of Infectious Diseases at the Vall d'Hebron Hospital in Barcelona.

A very diverse virus

The idea has always been to teach the immune system to recognize and fight this foreign invader.

In one way or another: vaccinating with an inactivated virus, using its envelope proteins or mixing various strategies to train the body's defenses to react quickly when they encounter the real virus.

But nothing has worked.

The first generation of vaccines —or attempts— was with the “classical models”, explains José Alcamí, a researcher at the Carlos III Health Institute and a member of the AIDS Study Group (Gesida) of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases.

For example, inactivated virus or HIV envelope proteins were used, with the intention that the immune system would learn to activate itself and generate antibodies when it encounters the real virus.

But, in practice, the immune response was very weak or absent.

“This strategy did not work because the HIV envelopes are very diverse between patients: the virus has an enormous capacity to evolve and mutate, much more than the flu or SARS-CoV-2.

We have many subtypes of HIV circulating at the same time and we are not going to have a protein that covers all that diversity for us, “says Mothe.

The scientific community also opted to develop vaccines that induce a response from the cells of the immune system: unlike the first generation, which sought to promote the formation of antibodies against HIV, now they were trying to encourage the production of another area of the immune system, the key cells in the antiviral defense (the T lymphocytes).

A prototype was the one studied in the STEP trial: an attenuated (harmless) version of an adenovirus functioned as a vehicle to transport three synthetically produced HIV genes with which it was hoped that, when in contact with the organism, it would recognize it and generate a powerful immune response.

But it didn't work either.

“They failed and, in addition, more vaccinated people were infected than in the placebo group,” recalls Alcamí, who is also a doctor at the Clínic.

In another twist to the research, an effort was made to create vaccines that combined the two failed strategies and simultaneously induced a cellular and antibody response.

A trial using this strategy in Thailand achieved 30% efficacy, but it also had its limitations, Mothe points out: “It was tested in people with little risk of acquiring HIV and with a subtype that circulates only in that area.

When attempts were made to reproduce in a population at higher risk and in other subtypes, such as the one that circulates in Sub-Saharan Africa, where there is a greater diversity of viruses, there was no sign of efficacy”.

The MOSAICO study, which has just been stopped, also belonged to this generation of vaccines that sought a double response.

Why have all attempts failed?

First, due to the variability of the virus, much higher than that of other microorganisms.

By the time the immune system detects the virus and reacts by creating antibodies, the virus has already mutated and when the body's defenses, created

ad hoc

For that first virus they come across, they start working, HIV generates, through mutation, variants resistant to those antibodies.

In addition, Alcamí points out, the antibodies are directed against that virus envelope protein that serves as a key to enter the cells, but accessing that molecule and neutralizing it is not easy.

He gives an example: “In SARS-CoV-2, the protein is like an open hand with five fingers and the antibodies are directed against those fingers.

In HIV, the protein has a clenched-fist structure and only unfolds when it interacts with the receptor [of the cell into which it is going to integrate].

The antibodies, even if we have them, do not reach those fingers because they are hidden in that closed structure”.

The body does not know how to attack the virus effectively, says Ana Céspedes, global director of operations for the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI), a global non-profit organization that investigates a preventive preparation.

“The number of dominant strains of HIV is 60 and they recombine with each other, which makes it very diverse: you are not attacking one virus, but many different ones,” she laments.

In addition, HIV attacks cells responsible for the immune response (CD4) and has a very rapid capacity to infiltrate and hide in the body, he adds: "Four hours after a sexually transmitted infection, the virus is already hidden ”.

Everything plays against.

“The body does not know how to attack the virus.

We have to be better than our body”, resolves Céspedes.

With the setback of the MOSAIC, the scientific community returns to the first steps in the race for the vaccine.

There is no other prototype, for now, in advanced clinical trials (phase III), although there are strategies in more initial stages.

In this new era of vaccine search, in December the journal

Science

published positive results from a phase I study with another approach based on highly neutralizing antibodies, a rare class of antibodies that can neutralize several virus strains at the same time.

It is not the first time that attempts have been made to induce these powerful antibodies with a vaccine, but so far they have not been successful because the immune cells (B cells) that produce this kind of elite army do not usually activate when they encounter the proteins of the envelope of the virus.

To get around these bumps, a protein that primed B cells to react was designed and a group of scientists tested its efficacy with 48 participants: the results, published in

Science

, show that they are on the right track, since after the vaccine, the participants increased the presence of precursor cells for these robust antibodies.

It is, however, "a proof of concept," say the authors, a crucial first step in the strategy to obtain highly neutralizing antibodies against HIV.

It remains a long way to go: this vaccine, by itself, cannot yet induce highly neutralizing antibodies mature enough to protect against infection.

In these elite antibodies may be the key to a future preventive vaccine.

But it will not be easy or fast, warns Céspedes.

Several types of these highly neutralizing antibodies, well matured and in high numbers will probably be needed to generate good protection.

“This makes us optimistic that there is a way.

There is light at the end of the tunnel, but we don't know how long the tunnel will be."

The Achilles heel of HIV

The war continues.

Another strategy underway is to try to

open

and make accessible that "closed fist" that is the virus's envelope protein, so that the antibodies can penetrate it and neutralize it.

In addition, this kind of armored structure has “Achilles heels”, Alcamí points out, which can give the antibodies an advantage: “Within these closed structures of the virus there are like molecular holes that the antibodies can reach”, he adds.

The Clínic and Carlos III are also designing another strategy against the virus: a vaccine that blocks the so-called founder viruses.

"If I get infected today, even if I get infected from a person with thousands of viruses circulating in his blood, the infective virus is one: the founder virus," Mallolas points out.

Researchers have found that these founder viruses have common characteristics and have designed molecules with those parameters to build their vaccine, but there is still a long way to go before seeing this prototype in a large-scale trial.

Eduardo Fernández Cruz, head of Immunology at the Gregorio Marañón Hospital, assures that the vaccine "will have to be capable of generating a very powerful neutralizing response, something that works very quickly to prevent the virus from deploying its escape mechanisms."

It is not an easy task.

But we must not give up on it, claims Ferran Pujol, director of the BNCCheckpoint community center, which recruited participants for the MOSAICO: “I am worried that funding will stop, that companies will abandon the search for a vaccine.

It is necessary".

Céspedes agrees about “the urgency” of continuing to investigate: “We cannot settle for chronic treatment, with having HIV in a little corner of the body.

Every five minutes a child dies of AIDS in the world.

This issue must continue to be on the agenda.”

A vaccine is not expected any time soon.

Some, like Alcamí, even doubt whether a preparation to prevent infection will ever be possible: “We still don't know if a vaccine against HIV will be possible.

We are in that degree of uncertainty.

We will see drugs that achieve a functional cure sooner than a preventive vaccine”.

You can follow

EL PAÍS Salud y Bienestar

on

,

and

.