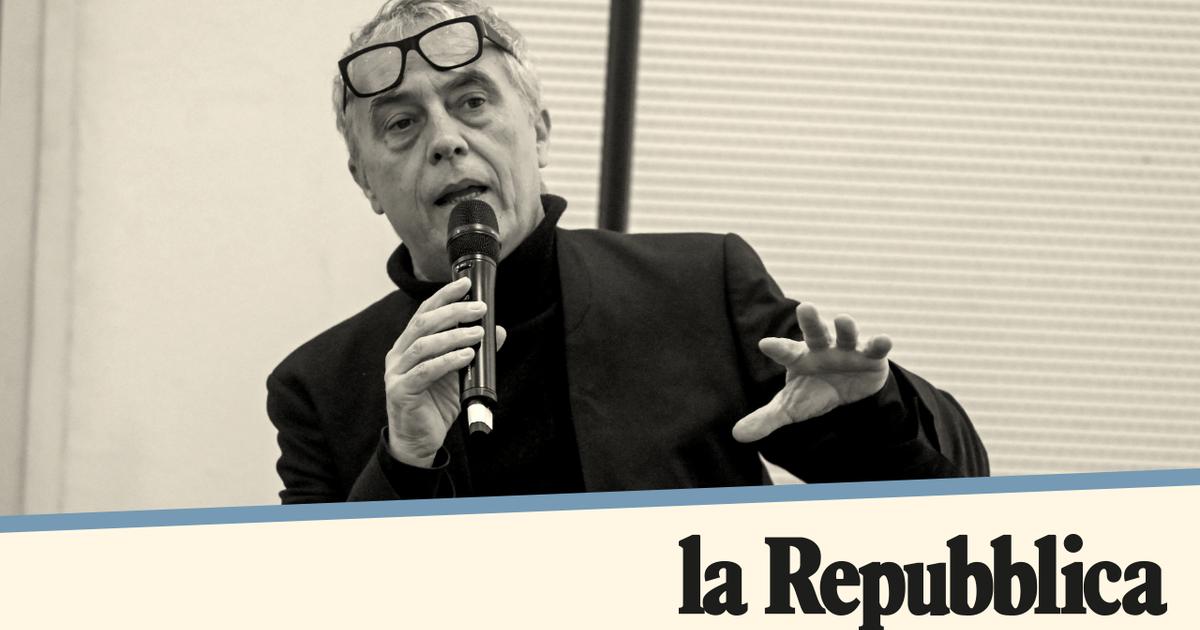

The Italian architect Stefano Boeri (Milan, 66 years old), who this Wednesday, February 15, receives the official Madrid Design Festival award, claims to feel especially linked to Spain.

“I am very happy to receive this award in Madrid, because when I left school in Italy we paid a lot of attention to Spain,” he explains to ICON Design by phone.

“On my first business trip, the director of Casabella

magazine

, Vittorio Gregotti, sent me to Madrid and Barcelona.

I met Oriol Bohigas and Rafael Moneo, who for me is one of the great heroes of architecture.

The Atocha station seems to me a masterpiece, because it is a large garden, an urban park, interior, of extraordinary dimensions.

When it opened it inspired me a lot.

Nobody did things like that."

The gigantic greenhouse inaugurated by Moneo in 1992 can be seen as a precedent, in a way, of the style trait that has placed Stefano Boeri on the media front page of recent architecture: his way of integrating vegetation into the structure of buildings .

The paradigmatic example is the Bosco Verticale, an imposing architectural complex that has radically transformed the Porta Nuova neighborhood of Milan since its inauguration in 2014. Each of the floors of these two towers, with 18 and 26 floors respectively, is dominated by trees that They grow on the terraces and ledges of the building.

This luxury building makes it possible to virtually transform an apartment 80 meters high into a small house with a garden.

And, by extension, create your own ecosystem,

View of Stefano Boeri's Bosco Verticale in the Porta Nuova area of Milan.Dimitar Harizanov

View of the Bosco Verticale in Milan by Stefano Boeri.dimitar harizanov

It does not seem strange, therefore, that Boeri confesses that his first vocation was not linked to architecture, but precisely to nature.

“I wanted to study marine biology and oceanography, but when I was looking for a university I realized that I was avoiding facing a taboo, because my mother was an architect and designer.”

She refers to Cini Boeri, a fundamental name in design from the sixties, seventies and eighties, author of sumptuous residences (the most famous are in Sardinia) and, above all, elegant and avant-garde furniture that continues to be produced today.

“I realized that she had a kind of block.

Architecture was my absolute passion, but I didn't want to repeat my mother's career.

So I enrolled in Architecture without telling her before, and I chose the field as far away as possible from the one she had cultivated.

She was a designer, and I focused on urban planning.

She saw the world from the objects, from inside the architecture, and I preferred to deal with the streets, with the city in perspective”.

Although he tries to avoid the influence of his mother ("within a family one cannot speak of influence, but rather of an inevitable inheritance that one discovers later"), there are projects that suggest a certain continuity.

We asked him about the Casa nel Bosco, a very delicate house that Cini Boeri built in 1969 in a birch forest without cutting down a single tree.

“It is clear that that project marked me, I perfectly remember visiting the works of that house that did not touch the roots of the trees, in which each wall, each opening, was built like a chessboard that respected each tree”, he replies .

But her motivations, she explains, were elsewhere.

On the one hand, in the architects she admired, such as Patrick Geddes: "he was an architect, but also a biologist, geologist, sociologist and politician,

with an alternative line to Le Corbusier and with opposing points of view on the relationship between nature and architecture”.

On the other, in an underground current linked to urbanism and the social, with names like Giancarlo De Carlo, a member of the influential

Team 10

, and ideologue of "vital energy as lymph of architecture", he explains.

However, when it comes to locating the inspiration for the Bosco Verticale, Boeri looks beyond the limits of architecture.

For example, the intervention

7,000 oaks

by Joseph Beauys, who promoted the reforestation of Kassel during Documenta in 1982, or

The Rampant Baron,

the novel by Italo Calvino published in 1957, a year after Boeri's birth, and which tells the story of an aristocrat who decides to live in the treetops.

“For me it was fundamental, because many years later, when we made the Bosco Verticale, I realized that I had tried to do the same thing as Cosimo, the protagonist of the book, who doesn't want to come down from the trees.

The fact of seeing the

skyline

of Milan filtered through the leaves of a tree whose roots are perhaps two floors below supposes fulfilling an implicit dream, an involuntary wish”.

Palazzo Verde, in Antwerp (Belgium). Paolo Rosselli

Told like this it sounds almost dreamlike, but Boeri's landscaped architectures are extraordinarily complex.

At a time when sustainability or constructive sobriety have become priorities for a new generation of architects, the Milanese's buildings have been described as "extravagant" due to their high maintenance cost.

But Boeri defends his approach precisely because of the delicacy and empathy that daily work with plants demands.

“We have had to learn trades that we did not know,” he replies.

“I have always been passionate about trees and I began to study botany.

When I set out to fulfill this dream of building a tall building with tree façades, I had the help of a group of experts who had to start studying things they had never studied before.

For example,

what does it mean to have a nine meter tree 120 meters above the ground, subjected to a lot of wind and with particular exposure to the sun”.

Boeri dwells on very significant details, such as the composition of the soil necessary to fix the trees to the ground, or the importance of humidity.

"What we do is create a vital space for the tree, and we try to respect it and build houses around that space, also anticipating its use, in the same way that a house must anticipate the future uses of its inhabitants," he says. he.

“The starting point is the tree.

It's a change of perspective."

or the importance of humidity.

"What we do is create a vital space for the tree, and we try to respect it and build houses around that space, also anticipating its use, in the same way that a house must anticipate the future uses of its inhabitants," he says. .

“The starting point is the tree.

It's a change of perspective."

or the importance of humidity.

"What we do is create a vital space for the tree, and we try to respect it and build houses around that space, also anticipating its use, in the same way that a house must anticipate the future uses of its inhabitants," he says. .

“The starting point is the tree.

It's a change of perspective."

And that change in perspective, he says, was much needed in a city, Milan, which has had a troubled relationship with green spaces.

“In a certain way Milan has always been a green city, because the Milanese courtyards since the 15th century were gardens, orchards and botanical parks, but at one time that history was canceled and forgotten.

It was not in Gio Ponti, nor in Aldo Rossi.

Today, in Milan, green is a formidable rediscovery.

I realized how disruptive the Bosco Verticale was because of the suspicions and accusations it aroused”.

The Wonderwoods project, in Utrecht, takes advantage of the possibilities of wood also as a construction material capable of reducing the building's carbon footprint.

After the impact of the inauguration of the Bosco Verticale, the Boeri studio has undertaken various projects inspired by the same philosophy in China, the Netherlands and Belgium.

“We are very lucky, because our work allows us to conceive architecture as a form of experimentation, trying to improve in each project”, he explains.

In Eindhoven, for example, the concept is transferred to social housing.

In Utrecht, a new vertical forest houses shops, offices, homes and

coworking spaces

, almost like a miniature city.

Work will soon begin on a building in Dubai where he puts many of his principles to the test.

“At the end of the day, sun, water and shade are the great challenges of the future”, he explains.

"This building absorbs the maximum possible amount of solar energy, consumes the minimum amount of water and casts shade on the facades, reducing the temperature inside."

Technical debates aside, the script twist introduced by Boeri in recent architecture is consolidated in the experience of inhabiting its vertical forests.

He himself, he says, rented an apartment in one of the Milanese towers, which he uses as a studio and as an example for future clients.

"It's a unique experience," he says.

“And the most beautiful thing is living in a building that changes every moment, depending on the inclination of the sun or the seasons.

It even changes the shape, because the plants grow, or prune them, and there are species that develop faster than others.

There are always unexpected moments.

We have had spectacular autumns, but this last autumn, for example, there was a drought in Italy and the plants suffered.

Of course, the vertical forest was less green, but that's life and that's nature, and that's why it's an incredible experience.”

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber