Between the motto of departure and the arrival of the weekly

Expresso

, the history of the last 50 years of Portugal can be read.

On January 6, 1973, even with the dictatorship in force, it presented itself as "the weekly for those who want to know."

Knowing in a dictatorship is not easy, but that phrase was both a commitment to freedom of expression and a nod to readers who were looking for some truth between the lines filtered by the censors.

Today, with more digital subscribers than print sales and with the national leadership of podcasts, it is distributed with this declaration of intent: “Freedom to think”.

From looking for readers who want to know to looking for readers who want to think, that is also the path that goes from dictatorship to democracy.

The project set up by Francisco Pinto Balsemão, one of the most daring Portuguese figures of recent decades, capable of combining business astuteness, political commitment and journalistic devotion, did not always manage to make what he wanted known.

From the time he took to the streets until the Carnation Revolution in April 1974, he suffered censorship interference in almost 2,000 texts.

Strange as it may seem, some unthinkable articles on colonialism, such as

A problem called Overseas

, signed by Balsemão, the weekly's main shareholder and first director, avoided the sieve.

A rarity that went well.

The businessman, who had entered politics shortly before with the naive idea of democratizing the dictatorship from within, was inspired by Anglo-Saxon media such as

The Sunday Times

and

The Observer

.

He liked the clear separation between opinion and information, the strict proportionality between importance and size of the news, international coverage and economic information.

He reserved 51% of the company and management.

He endowed the newsroom with clear bodies such as the editorial statute, with a supreme commandment: "Serve the national interest, regardless of the government that is in power."

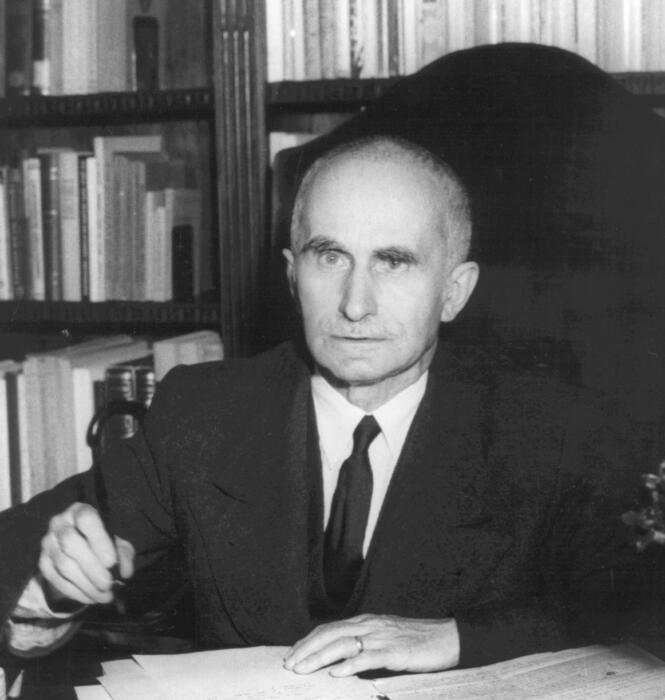

Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, Francisco Pinto Balsemão and Augusto de Carvalho review tests of the 'Expresso' in 1972, one year before it hit the streets. Reserved Rights

Through thick and thin he kept the name he had thought of and that no one liked because it reminded him of a midnight train.

He signed, among others, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, an intelligent Law professor, son of the regime's Minister of Health who would end up being President of the Republic from 2016 to the present day.

Rebelo de Sousa was the second director of

Expresso

, when Pinto Balsemão entered the government of Francisco Sá Carneiro, whom he would replace as prime minister in 1981 after his death in a plane crash.

The disagreements between Rebelo and Balsemão are mythical.

Suffice it to say that, in his memoirs, the founder of

Expresso

compares the nature of the current Head of State with that of the scorpion in the frog story and recalls that, when Rebelo left the weekly and a debt was claimed from him, he sent the amount in bills little ones in a shoebox.

This, however, has not hindered Rebelo de Sousa's decision to recently award the Order of Freedom to the

Expresso

and honor its founder: “he never wanted to be an absolute monarch, neither then nor today.

This is extremely rare in Portuguese society.

It is his strength and that of his project ”.

In his memoirs, Balsemão compares Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, second editor of the weekly, with the scorpion in the frog story

The separation of Balsemão's different worlds was more complex during his time as prime minister and leader of the Social Democratic Party (PSD, centre-right) which he helped found.

The criticism he received from

Expresso,

of which he continued to be the main shareholder, made him gain prestige in journalism and lose it in his party.

"In general they said: 'If he does not rule the newspaper that he founded and which is his, how is he going to rule the country?", he writes in his Memoirs

of

him.

After half a century of life, the header enjoys widespread respect, both nationally and internationally.

“The best proof that the

Expresso

is independent is that the Portuguese leftists say we are right-wing and the Portuguese right-wingers say we are leftists,” says its current director, João Vieira Pereira, who was born 16 days after the departure. of the weekly with this daring headline: “63% of the Portuguese have never voted”.

In the country with the longest dictatorship in Western Europe, a quarter of the population was illiterate, sought prosperity in emigration and endured three wars in Mozambique, Angola and Guinea-Bissau.

João Vieira Pereira, director of the Portuguese weekly 'Expresso', in the newsroom at the end of January. JOAO HENRIQUES (JOAO HENRIQUES / EL PAIS)

Not only was the censorship of the dictatorship traumatic, but also the months of the so-called Revolutionary Process in Progress (PREC) that followed April 25.

In 1975, 300 companies, including banks, were nationalized, land was occupied, and sovietization began.

"As

Expresso

became the only national media outlet not controlled by the Portuguese Communist Party and its allies in the Armed Forces Movement, the siege began to close," recalls Pinto Balsemão in his Memoirs, who came to

walk

with pistol in the car in those days when Portugal was approaching civil war.

The comings and goings between politics and journalism are part of the idiosyncrasies of the medium, but its current director does not see that this is holding him back: "I think I have more freedom here than in other media."

João Vieira Pereira, who joined the weekly in 2006, has his own story to prove it.

As an economic journalist, he was among the first to write about the case of Banco Espíritu Santo, which would end up collapsing Portugal's most powerful industrial financial empire in 2014. The bank was the main advertiser of

Expresso

.

"The only pressures that I did not receive were the internal ones," he relives.

It was the only time she felt fear, although she released it by writing more and more about it.

It was also the only time that they tried to bribe him with a job offer of those that carry a salary that cannot be refused and that he rejected.

A break in the newsroom of the Portuguese weekly 'Expresso', with its director, Francisco Pinto Balsemao, in the center, in January 1974 or 1975. EXPRESS ARCHIVE

There were also professional crises such as the departure of part of the newsroom to found the

Público

newspaper in 1990 or the computer attack they suffered a year ago.

Also satisfactions such as attending an increase in sales in a pandemic.

“We were the first to affirm that a million people were expected to be affected, they attacked us a lot for being sensationalists.

Reality would prove that we failed by default”, recalls its director.

Good information has to pay

Joao Vieira Pereira

With a staff of 70 journalists and two permanent correspondents (Brussels and the United States), the weekly has 48,000 digital subscribers and sells 44,000 printed copies.

Digitally, it is already a newspaper that reports from Monday to Sunday.

“Paper will not disappear, digital will not kill newspapers in the same way that

podcasts

will not kill radio and

streaming

will not kill television”, reflects João Vieira Pereira.

“We believe that good information has to be paid for, that is the way.

The

Expresso

is profitable and wants to continue being so because it is the guarantee of independence”, he adds.

The technological and social revolution has had a full impact on journalistic businesses but, in the director's opinion, it also reveals that "we need journalism more than ever."

In this half century Portugal has established itself as a firm democracy.

The journalist underlines freedom as the great victory (“People do not have retaliation for thinking, writing and saying what they think”) but laments the persistence of inequalities.

In his articles, he reproaches politicians for working harder to make foreigners happy than Portuguese.

“This paradise must also be for those who live here”, he concludes.

Follow all the international information on

and

, or in

our weekly newsletter

.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/2C5HI6YHNFHDLJSBNWHOIAS2AE.jpeg)