The Mexican president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, used to paraphrase the famous quote — “Poor Mexico, so far from God and so close to the United States” — coined by General Porfirio Díaz to synthesize the thorny relationship with the northern neighbor, invasion included, during the 19th century.

López Obrador now uses it with a slight change – “Blessed Mexico, so close to God and not so far from the United States” – and with a very different intention, to demonstrate harmony and build bridges with the Joe Biden Administration.

Although in recent years the appointment reformulated by the Mexican president can be found even a greater meaning and journey.

At least if you consider the decisive role of the US Justice in the fight against organized crime.

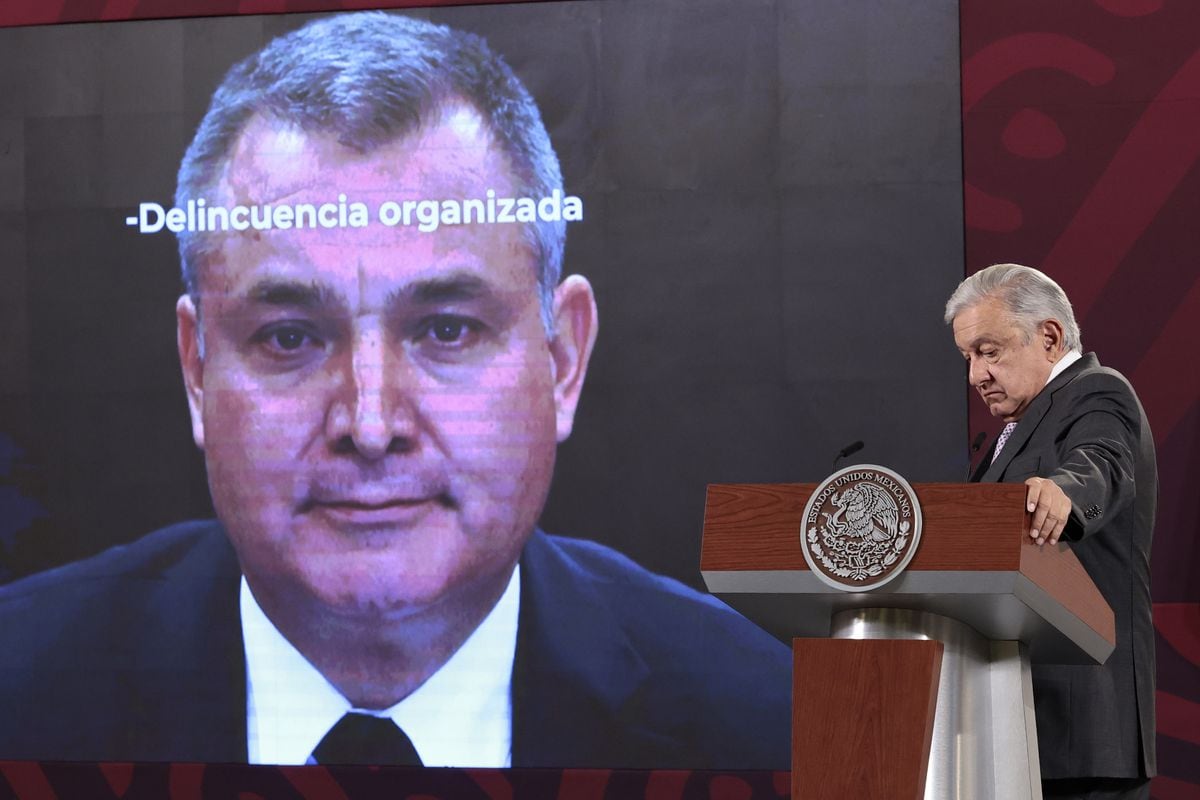

This Tuesday's sentence against Genaro García Luna, found guilty of up to five charges in a New York court, including drug trafficking and organized crime, is the latest episode —and the most important as it is a former Secretary of Public Safety— within a long series of legal proceedings north of the Rio Grande.

Some blows that began, precisely, with the so-called war against drugs that began in 2006 by the government of Felipe Calderón, of which García Luna became one of the most powerful men.

Over the past nearly two decades, arrests have been made on American soil.

While the Mexican governments of all colors have undertaken a determined policy of extraditions of big bosses.

During Calderón's tenure alone, 498 people were extradited, doubling the figures of his predecessor, Vicente Fox. The figure of El Chapo Guzmán, also tried and sentenced to life imprisonment in New York after escaping up to two times from a maximum prison security in Mexico, is the greatest symbol of this particular transfer of powers between neighbors.

Just as the US relocates its factories to seek to produce cheaper in the south, it seems that Justice follows the same logic, although in the opposite direction:

A Mexican trial with US rules

The asymmetries were evident from the beginning of the García Luna trial.

While the political storm raged in Mexico, interest in the case in the United States was minimal.

The journalistic chronicles that talked about

Mexico's Top Cop

, the Mexican supercop who was risking his fate in a New York court, faded after a few days in the information cycle of the most powerful country in the world.

While the Spanish-language media collected every detail of the testimonies that splashed and stirred up the highest political spheres south of the border.

It was a “Mexican” trial: because of the nationality of the defendant and the key witnesses, because the crimes were committed primarily in Mexico and because it had its most interesting passages in Spanish.

But it was always clear that the rules of the game belonged to the United States and its justice system.

The most important trial against a former Mexican official was held in the United States and that had profound implications.

The endless debates over the preponderance of testimonies over physical evidence and the commitment of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador to capitalize on the result were left at the gates of the court, as were many of the most controversial episodes in García Luna's career.

Instead, the fate of the former secretary was placed in the hands of a group of 12 citizens with little knowledge of the Latin American country's drug war, let alone who was accused.

The members of the jury did not know about the scandals due to assemblies, the fortune that the Mexican government is still pursuing or the immense power that the former official amassed.

Even so,

The defense produced five photographs of the defendant with figures including former President Barack Obama and former presidential candidates John McCain and Hillary Clinton.

The jurors, however, were also unaware of the close collaboration between Mexico and the White House during the government of Felipe Calderón.

While the testimonies sparked waves of accusations against authorities and public actors at all levels in Mexico—former presidents, governors, cabinet members, judges, police, military, and journalists—no mention was made of their American counterparts.

Nor were many explanations demanded from the press or civil society in the US The trial managed to escape the political hurricane in Mexico, but very high costs were paid for it.

The process against García Luna in Mexico was a kind of examination of the controversial anti-drug policy of the Calderón government.

But also a reflection of the asymmetries that exist in the relationship between the two countries, of the incompatibility of their priorities and realities, of what was a historic failure for one country and practically unnoticed for the other.

subscribe here

to the EL PAÍS México

newsletter

and receive all the key information on current affairs in this country