EL PAÍS offers the América Futura section open for its daily and global informative contribution on sustainable development.

If you want to support our journalism, subscribe

here

.

Tomás searches the sand for the remains of dead crabs.

When he finds one, he holds it up for a closer look.

It is five in the morning and the sun is already rising in the delta of the Colorado River.

“See this?” he asks.

Many crabs die from lack of water, he explains.

The estuary has been punished by the lack of fresh water that caused the death or departure of thousands of species.

The most visible proof of this is the remains of dead crabs lying in the middle of what is now a desert.

But Tomás Rivas, a 47-year-old marine biologist, is part of an alliance of non-governmental organizations that have been working for a decade to recover the river's ecosystems that have been disappearing since the flow of water was cut off.

In recent years they have managed to get the native species to begin to return little by little.

What happened to Tomás and his companions seems like a fight against the current every day.

Just hours before, they were celebrating a milestone: the Colorado River bed had come to join the waters of the Gulf of California.

A century ago, the river flowed normally from its source in the American Rocky Mountains to the Sea of Cortez.

But since Mexico diverted the river into a canal system in the 1940s, the encounter between fresh and salt water hardly happens anymore, because the river has been reduced to 3% of what it was.

Those days, after a lot of work, they managed to make a timid river finally flow into the delta.

Between hugs and happy faces, the team explains how difficult it is for that to happen.

“It was just a trickle of water,” says Rivas, a member of the Sonoran Institute organization.

Tomás Rivas Salcedo in the estuary located south of Mexicali, Baja California State. Iñaki Malvido

This association is one of the six that work in Mexico and the United States to save the Colorado River and recover the ecosystems that have been lost due to drought.

The organizations are made up of technicians, engineers or oceanographers who dedicate their knowledge to combat climate change.

They are all dedicated to reforesting hectares and creating green lungs where there are none.

One of them, ProNatura, also works to monitor birds, which have returned to populate this corridor after the restorations.

Another, Let's Restore Colorado, has developed its own nurseries to produce thousands of trees that are later used to build forests in the middle of the desert.

The problem they face is drought in all its faces.

The governments of the United States and Mexico, which share three water basins —Río Bravo, Tijuana, and Colorado—, signed a treaty with the latter in the 1940s to guarantee the annual delivery of water to its neighbor to the south.

But due to the changing conditions that the Colorado River has gone through, the agreement has been updated with different acts signed by the two countries.

One of the latest, the 323, of 2017, establishes that there is a portion of the water that has to be used for the environment.

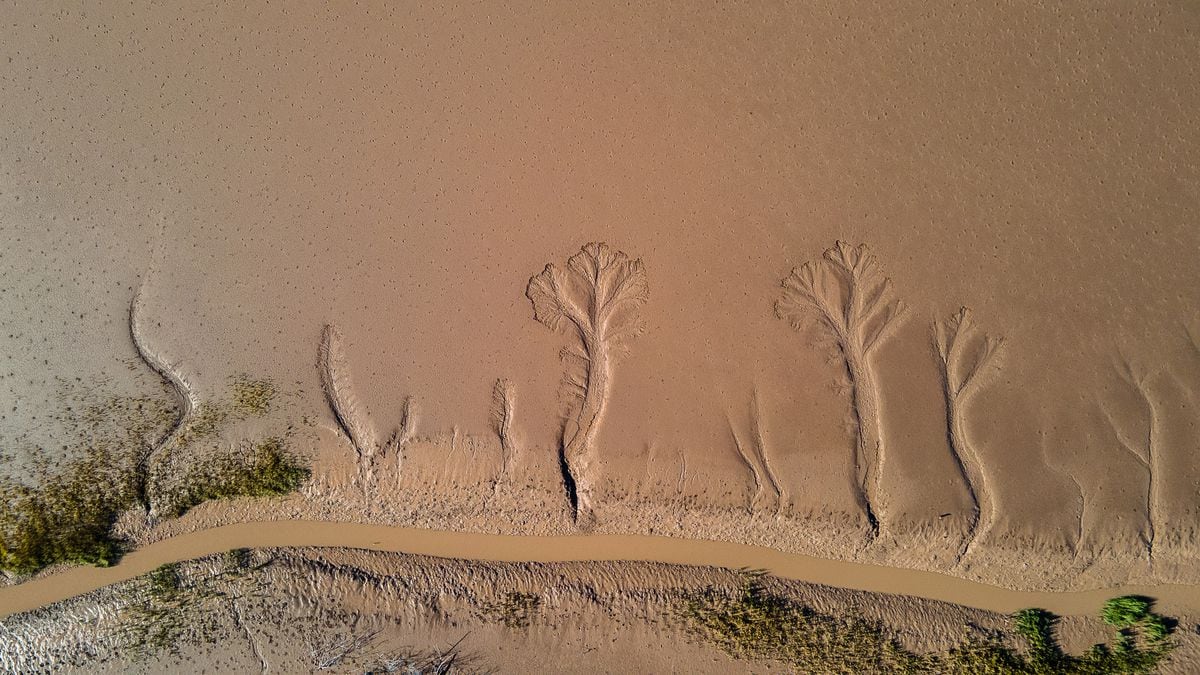

The "little trickle of water" that stretches to the Sea of Cortez, thanks in part to the full moon that raised the tide the night before. Jesús Salazar (Alianza Revive el Río Colorado)

The area through which the Colorado River historically crossed in Mexico is desert.

The Government of Miguel Alemán inaugurated the Morelos Dam on the border in 1950, the first diverter in the country —which diverted the water from the river to a system of canals—, designed to enter the largest amount of water that reached the State of Baja California and thus avoid losing bulk of this liquid.

This implied that the natural channel disappeared, and as a consequence, green spaces that were around its entire route died.

In Act 323, both governments and a group of NGOs agree to contribute 86 million cubic meters of water in equal parts in order to recover the ecosystems of Colorado, improve the conditions of the estuary, and recharge the aquifer.

In addition, the three signatories each promise to contribute three million dollars for scientific research and monitoring;

and another three million dollars more for restoration of sites, such as reforestation with native tree species or recovery of habitats.

By the end of 2022, the parties had already complied with half of what was established.

Those commitments have begun to show their shape years later.

And the positive impact of those promises made in 2017 have begun to be reflected in projects such as the Save the Colorado River Alliance.

The group brings together six organizations, three Mexican and three American, which operate in the seven US states through which its channel crosses and in the Mexican state of Baja California.

On the southern side of the border, a dozen sites have been successfully restored.

The Morelos diversion dam, which redirects most of the channel towards the irrigation canal (which flows to the left of the image). Jesús Salazar (Alianza Revive el Río Colorado)

Ecosystems regenerate with water

In order to make a more strategic restoration, the organizations have agreed that official water deliveries be made through the canals at specific points, where they have invested to accompany this delivery with a reconditioning of the site.

An example is Chaussé, where throughout last summer the NGOs were counting each liter that entered.

There, some 74 hectares were reforested with some 25,000 trees.

The success has been such that it has caused the return of animals that were no longer seen.

In those days, NGO workers enthusiastically photographed a family of beavers that had arrived at their restoration site.

The reforestation in that place was designed by the organizations thinking about climate change and the possibility that in the future there will be no water to distribute.

With that idea in mind, the trees that were planted, explained one of the engineers to América Futura, had a drip irrigation system that fed the flora with very little water.

Two Sonoran Institute workers measure the liters that are delivered to an environmental restoration site.Iñaki Malvido

The goal is to use water wisely, punish trees so they are able to develop more roots, and seek water from the groundwater table.

The teams want to prepare the species to face lack of water in the future, without going extinct along the way.

“They have been working on this in the United States for a long time, but in Mexico we are more passive,” explains Enrique Guillén Morán, head of irrigation for the NGO alliance.

The teams have restored part of the forests that originally inhabited the place.

"At the beginning of the 20th century, when the flows of the Colorado in Mexico began to be interrupted and the normal channel was channeled to be used for agriculture, all the poplar and willow forests died, all the native vegetation died," says Eduardo Blánquez, Restoration Coordinator for the organization Let's Restore Colorado.

The reforested area of the Miguel Alemán restoration site, surrounded by arid desert and agricultural land. Jesús Salazar (Alianza Revive el Río Colorado)

Inside the small green oases that they have built, the air that is breathed is three or four degrees cooler than the sweltering heat of the desert.

The natural regulation of temperature is one of the benefits of reforestation.

Blánquez explains others, such as the production of seeds used as fodder for local livestock or the reconstitution of food chains.

The sites are also carbon sinks and wildlife sanctuaries.

“We are doing our bit to mitigate climate change, not just helping ourselves, we are helping the world,” he says.

Another site is Miguel Alemán, on the border with the United States.

On the other side of the wall you can see a restored site a few meters away.

On the Mexican side, they raised one to create a bird corridor.

“This is a very important migratory corridor for birds, so spaces had to be created for them,” says oceanographer Gabriela Caloca, coordinator of water and wetlands at the organization ProNatura Noroeste.

That's why they built a 170-hectare forest from scratch.

"Miguel Alemán is that, to demonstrate that it is possible to restore a site that was thought to be completely dead, already abandoned."

Reforestation there brought back about twenty bird species.

Their monitoring of the species involves catching them, putting rings on them to mark that they have been there, and releasing them again.

Among the birds that count on the return are the verdigris, the roadrunner, the cowboy and the basketball, say the workers of the place.

The restoration in the middle of the desert has made that point, like the others recovered, fill up in the summer with visitors who seek to appease the heat in nature with fresh air and a little water.

Alejandra Calvo from ProNatura holds a bird in front of the book she uses to identify it.

It is a juvenile verdigris, even without the yellow head that characterizes them, which fell into the bird monitoring networks of the Miguel Alemán environmental restoration site. Iñaki Malvido

Calvo inspects the width of the verdin's leg.Iñaki Malvido

After measuring the width of their legs, the length of their wings and placing a ring that identifies the individuals that have already been seen at this site, check the wear on their feathers.Iñaki Malvido

The tools with which bird monitoring is carried out, in which a series of metrics are noted to see the type of birds that arrive at the restoration site as well as their state of health.Iñaki Malvido

All the teams that operate in the restoration sites are made up of scientists and academics who, before taking a step, analyze each circumstance and consequence.

A few kilometers from Miguel Alemán, in a town called Janitzio, Caloca raises his hand and shows a property that looks like a dump.

This is the last project of the alliance, where they will put their resources, water and money, to be able to raise a new green lung on these inhospitable lands.

"This is how each site was before it began, but we will do the same thing that we have done in Miguel Aleman here."