The happy don't have time to write diaries, they are too busy with life," once wrote the American author Robert Heinlein. It is possible that not all diary writers would agree with him, but Avishi Dafni and Galila Sharifim, the grandchildren of the late Zehava Pitsakia, are sure that their grandmother would have signed his observation without hesitation .

Although Pitskia's life brought her a long relationship with one of the most important leaders of Israel's revival in the last century, when she passed away in 1966, no national day of mourning was declared, no state ceremonies were held, and no grave was dug in the plot of the nation's greats.

Her family and her few friends accompanied her on her last journey, and later discovered among the details of her meager estate notebooks of yellowed pages written in Russian.

Coming from a background of extreme poverty in the crumbling empire of the tsars and struggling to make a living, she didn't leave much behind, except the diaries she kept for almost four decades, since she was a teenager.

More than a year after her death, the treasure hidden between the pages of the diaries was finally revealed to the public at the National Library.

Diary operation at the National Library.

Writer: Yori Yalon // Photography: Yoni Rickner

"Everything in these diaries is very personal: a private story that is exposed, at times very intimate, that leaves no one indifferent," says Galila Seferim, Piteckia's granddaughter.

"This is not the dry history that we are familiar with from textbooks. Unlike other pioneer diaries, there is not much concern here at all with national matters, and even founding events, such as the Declaration of Independence and the War of Independence, are barely mentioned. Our grandmother's diaries are a personal testimony, free of filters, about life If you will, this is the voice of someone who lived on the margins of the historical event, an account of what a poor woman could experience and tell with utmost sincerity in the 20th century."

Matan Barzali, director of the archives of the National Library, admits that the story of Zehava Pitsakia's diaries touched him in a special way.

"Zahva's grandchildren approached us about a year ago, and it took us a while to understand the potential that lies in this thing, what's more, they themselves couldn't understand what was written in Russian," he says candidly.

"But as soon as we understood - we absorbed the archive in its entirety and made accessible the parts of it that are open to the public. Its richness and depth prove once again that history is also written by ordinary people, and not only by soldiers and heads of state. Archives always reveal the lesser-known sides of history, the different angles and the various ones that didn't make it to the books, which is why they are so interesting and attract energetic researchers again and again.

"Within this whole complex called 'archives', personal diaries are a unique literary genre, because they are the truest and most authentic means of expression. They are written in real time and without a recipient, which allows the owner of the diary to humble his or her most hidden insights and thoughts ".

Insights into the place of the Russian influence on the settlement and its people.

Zehava's diary, photo: Oren Ben Hakon

"I want to remember everything"

Secrets of capsules are not lacking in Pitsakia's diaries.

Barzli emphasizes that he has no intention or motivation to reveal secrets that people want to hide and that concern individual modesty: "We take into account that there are things that the descendants of the diary writers will not want to reveal. As the trackers said: 'There are things that still cannot be talked about since 1948.''" Personal diaries are taken into the National Library subject to a request for confidentiality for several years, as long as they have an expiration date within the foreseeable range."

Even the partial secrecy will not prevent Pitsakia's diaries from attracting attention and causing quite a bit of controversy, perhaps precisely because they were written, from beginning to end, from a personal point of view, and perhaps because the main feeling preserved throughout them is the writer's sense of difficulty.

The difficulty reaches dramatic heights in a series of terrible tragedies, including the loss of her daughter Galila, who died of an illness at the age of 10. "It is not the pangs of conscience that torment me, nor the feeling of guilt before her, but awareness of my miserable life," wrote Zehava two weeks after the death of her eldest daughter in one of the most moving episodes of the diary, and immediately added to the pain other feelings, honest and unusual for the period of mourning, regarding the girl and her father, Shmuel Arnan: "I hate and detest the father, and I would do everything I could to erase even his memory. A vile and wretched coward. I did not love her, and I could not touch her . She reminded him so tangibly in her face, in her body shape, in her words, in everything."

But the diary, the writing of which accompanied her throughout her life, begins with other, much calmer words: "What I want to write down I am sure will never be erased from my memory, but despite this I still want to remember everything and write it down. I will start by saying that when everything happened in Odessa in 1916 , on May 2..."

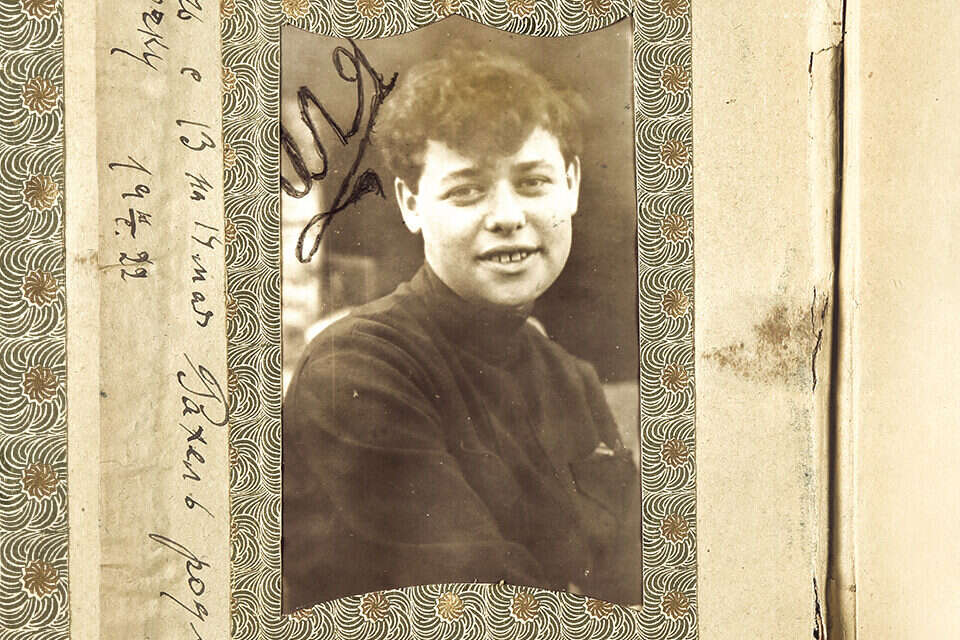

Piteckia started writing the diary when she was only 16 years old.

Naturally, she first detailed her childhood experiences, which foreshadowed something of what would await her in the future.

"Her parents wandered in the Crimean peninsula and in the areas of southern Ukraine near the Black Sea," explains Avishi Dafni, granddaughter of Pitskia and Yitzhak Sade, her mythological partner and founder of the Palmach. "Every few years they changed places, and Vazhava, or Golda in her Yiddish name, was born in the city of Kerch.

They lived in abject poverty, and it is no coincidence that she writes in her diary that the hardships of childhood and youth in Russia haunted her throughout her years."

"She studied until the age of 10 in a Jewish school, where the language of instruction was Russian and where her parents were not required to pay school fees," says Dafni.

"At the age of 11, she was sent by her parents to work. At first, she worked in the market and sold cookies as a peddler. Then she moved on to become a tailor's apprentice, and from the age of 12 to 14, she was employed in a hat shop, until she was fired from there when the First World War broke out. It is chilling to read how a little girl was sent away in the middle of winter to draw water from the frozen river or she was forced to go outside and beg after customers who left the store without buying anything. At least the little money she earned helped her not freeze - with her first salary she bought herself a coat."

Little Golda's family assimilated, but did not completely break away from Jewish tradition.

As evidence, Avishi brings one of the early stories from the diary: "When my grandmother, as a young girl, fell in love with a soldier who was not Jewish, the parents ended up telling him to cut off the unwanted relationship with Ivo and simply imprisoned her in the house, until the object of her love was transferred to another place."

Instead of a first love, another love came, and Pitskia left home with a friend, an architecture student named Shmuel Arnan, who became her first husband.

In November 1920 they immigrated to Israel, but even before that fate brought her together with Yitzhak Landoberg - later Yitzhak Sade.

A story in two voices

The diary reveals for the first time the circumstances of their acquaintance.

Contrary to the version accepted among historians, it happened back in the Crimea, before each of them traveled to Israel.

However, love did not ignite then.

"Zahva writes that they met in Simferopol, the capital of Crimea, as part of the youth group of the 'Halutz' organization, but Yitzhak Sade, who was ten years older than her, did not exactly pay attention to her, and was even responsible for the fact that she initially did not receive a certificate for aliya," explains David Gendelman , historian and researcher of the period.

The romantic relationship between the two was forged already in the Land of Israel in the 1920s.

Yitzchak, who was a strong bodybuilder with a muscular build, was used to attracting the attention of girls, and Zehava also fell into his net.

"Manual labor in quarries and mines had surprising advantages," Gendelman says with a smile, "but he also engaged in weightlifting long before bodybuilding was born as a fashionable hobby for young people, he guided Jewish boys in athletics and physical education in the 'Halutz' and 'Maccabi' back in Russia, and in Israel he was One of the founders of the Hapoel Sports Association."

This was just the beginning of a complex and winding story, which would not have embarrassed a sophisticated telenovela or a novel in sequels.

Zahva broke up with Arnan after they had a daughter, Galila, and had trouble supporting her.

She returned to Tel Aviv and to her husband, but separated from him again, gave Gilila to the labor battalion and went to Paris, where she met another friend, Izik, and lived with him for about a year in a commune of young Jews, including the poet Avraham Shalonsky and his brothers.

"After a year in Paris, she returned to Israel," adds Daphne.

"Izik stayed behind and passed away a few months later, but he was apparently the great love of her life. So much so that the girl who will be born to her is Yitzhak Sde, she will insist on naming Iza, after him."

"really want you"

The romance between Zehava and Yitzhak Sde resumed in 1926, following Sade's separation from his first wife and her return to Soviet Russia, many chapters of her diary are dedicated to him, and especially to the pain he caused her for almost 30 years.

Sade's character, as depicted in the writings, is far from a portrait of an ideal man, to say the least.

"He wasn't always able to give Zehava the love and stability she needed, but at least he sent her dozens of letters," Gendelman says.

"You can interweave the letters with the chapters of her diary, and then the historical story begins to speak in two voices."

Sade does not write in letters about things that are out of the ordinary.

Instead he shares little anecdotes with his lover.

In one of the letters to Zehava from 1936, when the Great Arab Revolt began, and Yitzchak Sde commanded the "Hanodad" - a mobile underground unit of the "Hagana" organization, whose job was to attack rioters in a targeted and proactive manner - he tells her that where the unit's members sit there is silence absolute.

He shares with her an amusing story about an Arab who speaks Hebrew, is married to a Jewish woman, works in Tel Aviv and even introduces himself there as a Jew.

According to him, that Arab was very offended after Sada said that he was now forbidden to have relations with his wife, because the Arabs of the country had declared a strike, the great Arab strike that lasted six months.

In the next line, he testifies that in response the Arab swore to him that he would not join the strike, which caused Sada to wonder about his own situation: "But why do I deserve this punishment! I'm not on strike! And I really want you."

Matan Barzilai, Director of Archives at the National Library,

In another letter, Sade tells the story of being Chaim Weizmann's personal security guard during his visit to Israel that year, after the outbreak of the events, and allows us a glimpse into the relationship that was forged between the two.

Weizmann understood that because of my face, "the face of a boxer", I could not be used for missions.

Not everything there is entertaining, Gendelman insists, far from it.

Some letters contain tragic and painful details, such as Sade's heartbreaking story about a Yemeni girl who committed suicide because of unrequited love for him.

Yitzhak Sade recounts in detail where and how they met, how they met here and there, how she told him that if he could not be with her she would not live, and ends by saying that she did take the poison.

Zahva apparently discovered this affair herself, Gendelman believes, and as a result he decided to bring the whole story to her.

Another motif, which is repeated in Field's letters to Piteckia, is a constant search for work and sources of income.

"They always lived in a pinch, in a lack of money," Gendelman clarifies.

"After they broke up, the details of the sighting arrangements with the girls emerge - when he does see them and when he doesn't. There were times when they got back together, then broke up again, and God forbid it repeats itself, until the final breakup following Sade's marriage to another woman."

To what extent was such a lifestyle acceptable in an age where the values of modesty are its own?

"Yitzhak Sade was widely known for allowing himself to do unacceptable things. Many people looked at him crookedly. Although he was considered an educational figure in the Palmach, in his relations with women he was unusual compared to the norms accepted at the time.

He used to hang out with young girls when he was already an adult, and attracted quite a bit of criticism for it.

"Even in the better times she had mixed feelings towards him," Gendelman adds.

"She complained that despite her love he looked at her as an object, and in general as a young woman she felt dangerous and rejected. 'What a great love I wasted on him,' with these words she bewailed her fate and explained that because of what she went through in childhood she was looking for a soul that would understand her, a true friend - she searched and did not find her In Yitzhak Sade.

"In the beginning, she saw him as an embodiment of a Greek god, and developed hopes for an immense love that would save her from unhappiness, but the hopes soon gave way to disappointments. Later, in the 1950s, the emotions change color to really dark tones, and hate takes the place of love.

"No one understands me"

"Zahava points out, for example, that his picture was published in the newspaper again, and he 'models her like a prima donna,' or complains bitterly that her daughter is starting to look like her father and behave like him. The frustrations in relation to those closest to her are joined by a constant tone of loneliness. 'I don't have a soul mate, and no one This world does not understand me', she writes repeatedly over the years. There is no doubt that she had objective reasons to look at the world with bitterness. She was a hard woman with a hard character, and life often showered her with hard trials and frustrations. Towards the end of her life, this bitterness probably turned into real depression , which lasted until her last day.

In the last chapters of the diary, the longing for death appears, and a dramatic "suicide letter" is also found, which opens with a triple exclamation: "Cursed! Cursed! Cursed!", addressed of course to Yitzhak Sade.

She tried to commit suicide at least twice, Gendelman notes, and concluded that death was better than her miserable life.

From a contemporary perspective, it is difficult to understand how Yitzhak Sade, one of the influential figures in the settlement, had difficulty supporting his family.

Yitzhak Sade, 1950,

"Sada didn't earn anything in his national missions, he wasn't a man who brought money home," says Gendelman.

"Even during the mission to secure Weizmann, he had to rent a room on the streets and take care of his bed and board, because he was not paid. During the time they were together, he never had any money. In the 1920s and 1930s, he traveled around the country, worked in quarries and tried all kinds of businesses. A project he took part in suffered financial losses until he went bankrupt. The family wandered after him - Yagor, Tel Aviv, Hadera, Haifa - moving from one rented room to another and only knowing a life of poverty.

"In general, if it weren't for the events of the late 1930s, it is possible that he would have continued to deteriorate and would have disappeared into the abyss of femininity without occupying a prominent place in the history of the settlement. Later, when he was already in the Palmach in the 40s, his financial situation may have improved somewhat, but Zehava She could not enjoy it, because they separated, and Sde lived with his third wife.

He held positions, but this was not expressed in money.

Zehava had to support herself and her childhood by working as a seamstress, hard physical work, especially if you take into account the basic sewing equipment of those years.

She hated this job, which didn't bring her a decent income anyway.

She writes that she always felt that she could have done something big and important in her life, to fulfill herself, but instead she was condemned to the ugliness of life.

There were periods when she wrote that she was actually happy for physical work 'to clear her head', but it is clear that this is not the fate she asked for herself."

How do you explain that Halutza's diaries, and Yitzhak Sade's letters to her, were written in Russian and not in Hebrew?

"Excluding those who ideologically advocated a demonstrable and complete disengagement from exile, such as David Ben-Gurion, writing in Russian - especially in personal letters - was a common thing in the generation of pioneers and the founders of the state. They continued to communicate in the language they knew, certainly with relatives or acquaintances from the past. For example, the letters of Avraham Stern to his mother and wife are written in Russian. When they still write in Hebrew, the handwriting is worse than the Russian. It is equally interesting that despite the lack of formal education, Zehava's language is rich. She compensated for leaving school at a young age by reading books."

Russian novel

The place of the Russian influence on the settlement and its people can be learned from many passages in Pitskia's diaries.

Thus, on September 3, 1945, she states: "Yesterday I listened to the radio from Russia and listened to a speech by Stalin who spoke about the end of the war against Japan."

Two days later, she complains that Y (Yitzhak Sade) too easily promises to take their daughter Rivka, who is in Tel Aviv, for a walk - and immediately adds that Rivka plans to go to the cinema to see a Russian film that is not exactly suitable for children.

"Grandma felt rejected," Daphne is convinced.

"She always had difficulty being accepted into the frameworks. She was an outsider. When she arrived in Israel, they did not agree to accept her into the kibbutz, partly because she was pregnant. In the early 1940s, while Sde founded the Palmach, she asked to join Kibbutz Yegor and was again refused, because Their little girl suffered from a leg disability.

Even in my grandfather's social circle, which included Alterman, Shalonsky and Rubina, she, with her four years of study, was a strange, different bird."

"Perhaps thanks to the disclosure of the diaries, the lost branches of the family will be found."

Zehava and Gendelman's grandchildren, photo: Oren Ben Hakon

Was Zehava a pioneer out of necessity?

"It would be more correct to call her a pioneer due to the necessity of the circumstances. She left home with a friend not because of a Zionist view, but simply because she was not comfortable there, and was attracted to a group of young Zionists. In fact, a woman who came from a low background had very few alternatives in those days. Grandma She experienced all the difficulties that were involved in the life of the pioneers in the Land of Israel, and even more. In some years she even considered leaving and returning to the USSR, and only the memory of her brother-in-law's murder during a pogrom stopped her.

"On the other hand, she became known as the second woman to join the Palmach, no less.

Kibbutz Yagur, where the family lived for a certain time, was one of the most important outposts of the Palmach, and the grandmother, who was the kibbutz's clothing warehouse, was also responsible for the Palmach.

Few people know, but she is the one who designed the one-pocket Palmach shirt for men and sewed black underwear for the members of the organization."

Barzli assures that making the Piteckia diaries public is just a shot in the arm.

"We are usually selective in depositing archives, after all, it is not possible to take in everything, what's more, there are other bodies in Israel that take in important archives and collections. Traditionally, the National Library receives personal archives of creators and intellectuals, writers, poets, thinkers and creators of culture.

"The new diaries project initiates an opposite, more inclusive move: we are opening the doors of the library and archive warehouses to anyone who wrote a diary during the years of the establishment of the state, and perhaps in the future we will expand this beyond the 1940s and 1950s.

"I think that quite a few houses these properties are passed down from generation to generation, until at some point the property becomes a burden. The library wants to be a home for those personal diaries, due to the uniqueness of the genre and the interest inherent in it," he adds.

Zehava's descendants have another practical goal in uncovering the diaries, which were until recently in their private possession.

"My grandmother's family stayed in Israel," laments Daphne. "In the early 1930s, she sent them money, even for herself it was barely enough.

After World War II and the fall of the Iron Curtain, traces of her relatives were lost.

Who knows, maybe thanks to the disclosure of the diaries, the lost branches of the family will be found."

were we wrong

We will fix it!

If you found an error in the article, we would appreciate it if you shared it with us