There is the Spain of the swimming pools and its reverse class: the Spain of the green awning.

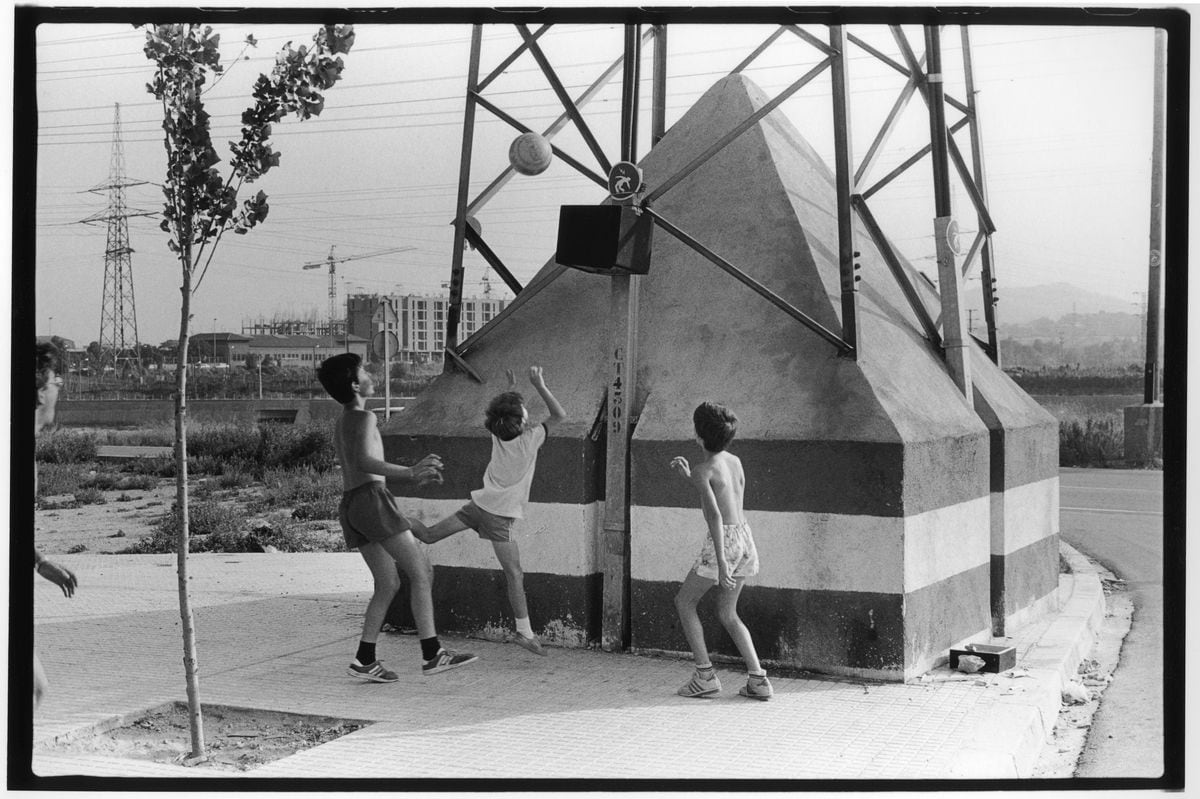

Now, perhaps without intending to, Manuel Calderón has configured another mythical territory, even more dislocated and vaporous: the Spain of the wasteland.

That untamed and moral territory of the periphery.

A non-place for nothing riddled with memory, ruins, working class and empty Sunday afternoons.

A lost paradise of childhood freedom where poppies, wheat ears and serial daisies, bricks and rubble, old mattresses, ripped-out armchairs, half-sunken recliners, a few syringes and many condoms flourished.

A wild land without authority where children play, young people fuck, dogs bark or old people long for.

The outskirts, the suburb, the periphery: a geographical, economic and sentimental coordinate.

The wasteland: urban fallow.

ontological void,

so precarious in its nakedness.

A space stalked today by urbanizations, polygons or shopping centers;

but above all, by law, administration and oblivion.

A land of dust and puddles where the emigrants who came from that other backyard dimmed with light drank: the town, rural Spain.

Like that family that one morning in September 1970 arrived in Barcelona after a night in the first-class carriage.

That she arrived with her suitcase on her back and ready to leave her past on the platform before taking a taxi to reach her new domain: the outskirts of the city.

the town, rural Spain.

Like that family that one morning in September 1970 arrived in Barcelona after a night in the first-class carriage.

That she arrived with her suitcase on her back and ready to leave her past on the platform before taking a taxi to reach her new domain: the outskirts of the city.

the town, rural Spain.

Like that family that one morning in September 1970 arrived in Barcelona after a night in the first-class carriage.

That she arrived with her suitcase on her back and ready to leave her past on the platform before taking a taxi to reach her new domain: the outskirts of the city.

Thus begins this singular work, more European than Hispanic in its form.

A great book that contains an essay, a chronicle, memoirs, travels, grafted aphorisms, philosophical reflection and a lot of opinion journalism.

Total nonfiction.

Some pages that still hide the light and accurate flight of the haiku camouflaged as poetic sparkles amerized from the baroque.

They take the spatial metaphor of the wasteland to narrate the true theme of the book: the passage of time.

Suspended, eternal, Proustian time.

Elastic time with music by Serrat, feats of

war comics

and I dripped on the wall.

Time for bars and billiards, telephone without prefix.

From a mother who came from Peñarroya-Pueblonuevo del Terrible.

From a metalworking father who smelled of rust.

That past time that never completely goes away for Manuel Calderón, who confesses that he has always felt uncomfortable with the future.

Even more so today, at the age of 65, he is convinced that the only world that matters has collapsed: everyone's.

The author admits slipping into some sour, vicious and quarrelsome writing in the political pages about Catalonia

The book is a cultural feast.

A very personal map of artistic references for this journalist, author of three novels —Bach

for the Poor

,

The Unfinished Man

and

The Gulag Musician—

.

It is also an atlas of elective affinities close to the spirit of the wilderness.

Albert Camus on the outskirts of Algiers.

Pasolini's corpse in an open field in Ostia.

The sky over Berlin

by Wim Wenders.

The affective desert of

Pedro Páramo or If they tell you that I fell

.

The naked poetry of Gil de Biedma or Claudio Rodríguez.

Lowry's sunny dryness and his volcano.

The rubble literature of Hermann Kasack.

The melancholic breath of Hopper's paintings or the

Bicycle Thief.

But there is much more.

The music of the Carpenters or Jimmy Hendrix.

The photographic purity of Cartier-Bresson.

Norman Mailer's journalism and his peripheral combat Ali-Foreman.

The extreme rationalism of the RDA architecture.

Kundera and the dictatorship of the heart.

Kertész and the freedom that smells like a corpse.

Or philosophers, many philosophers like Lukácks, Habermas or Elias Canetti, with their

Mass and power

in the background of the

procés

.

Precisely the political pages on Catalonia are the ones that deviate the most from that very original idea of the wasteland.

The author admits to slipping into some sour, vicious and quarrelsome writing in those passages.

That's how it is.

This descent into the Catalan political wasteland, which he sees as full of filthy rubbish and resentment after having left Barcelona and gone to live in Madrid, takes away from the book's literary flight, amputates its depth and attenuates its ambitious complexity.

However, I prefer to stick with the lightness of its boot.

With the sensitivity of his gaze.

With the truth that oozes the book.

Above all, I prefer to stay with the success of the fragmentary structure, so Sebald's, with its cultural excursions and digressions composing small tesserae —or better:

Rescue a phrase from Ernst Bloch: "He who dreams is never tied to the past."

Dreaming backwards or dreaming forwards: that was the dichotomy for so many families in rural Spain that emigrated to the edge of the urban wastelands.

From Madrid, from Barcelona, from Valencia, from Bilbao.

That progress that in Spain was called developmentalism and that, in the words of Calderón, was "like speeding up a pessimism cultivated for centuries."

In that game of mirrors that is the passage of time, the loss of rural roots and his particular view of

charneguismo

, the author writes: “Dreaming costs nothing, but it is dangerous.

Only a few end up trapped in that fiction and in the end utter the miraculous word: I am fully integrated.

Strange anomaly that of the man who crosses a mental border.

The worst".

Manuel Calderón emphasizes that a landscape is a point of view.

It is the choice of the place from where you look.

He has written these pages from the freest and most eternal wilderness: childhood.

From there he has composed these

Goldberg Variations

on that other wasteland, sometimes inhospitable, other times melancholic and almost always unaware that it is life.

Find it in your bookstore

You can follow BABELIA on

and

, or sign up here to receive

our weekly newsletter

.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber