This article is taken

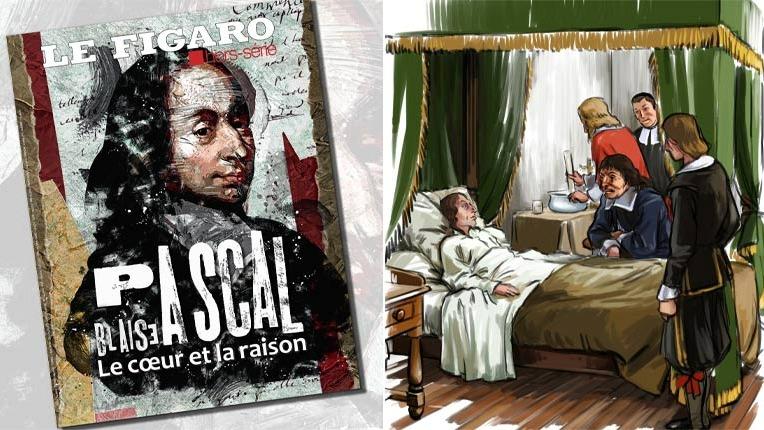

from the Figaro Hors-Série Blaise Pascal, the heart and the reason.

Eight years earlier, in 1639, he had admitted his talent only with a rather bad grace.

When Father Mersenne, an illustrious mathematician throughout Europe, extolled to Descartes, who had been living in Holland since 1628, the merits of this young Pascal, son of the man who had taken part, not without reason, in his scientific controversies with M. Fermat, Descartes had assumed knowing faces.

"

M. Descartes, who admired almost nothing, concealed as well as he could the surprise that this marvel caused him

», notes in his Life of Monsieur Descartes (1691) Father Adrien Baillet, remarkably informed by the study of his correspondence and the testimonies of his contemporaries.

All the old mathematicians could well go into ecstasies in front of this sixteen-year-old boy who had gone further than all his predecessors in the matter, up to Apollonius... What was it strange to go further? that Apollonius, who was long and embarrassed, and moreover had not pushed his researches on conics very far?

And besides, wasn't the real author Étienne Pascal?

Read alsoThe editorial of Le Figaro Hors-Série: Blaise Pascal, a man for eternity

The illustrious Descartes had to face the facts: the son Pascal was a young prodigy.

And if, to evoke the arithmetic machine and the theory of the vacuum with which all Europe rustled, he took care to visit him at home, during one of his three trips to Paris, when in the grip of one of his bouts of languor, Blaise was bedridden, it's good that the lord of mathematics recognized in this youngster a peer.

He had, moreover, conveyed this rather curtly to Gilles de Roberval who, finding himself there also and believing that the patient was confused, had spontaneously taken it upon himself to interpret Pascal's thought for Descartes.

It was him and none other that the master wanted to hear.

Blaise had related his conceptions of the void,

The month of September, 1647, was drawing to a close, and the young man was working on his abridged account of these conceptions of the void.

The conclusions he drew were clear: the void existed, he would soon prove it.

He had, in passing, created a scientific style, allied to his practical spirit.

If only his strength had not left him... After so many watches, of work to perfect his arithmetic machine, he had fallen into a languor and a state of weakness such that the doctors consulted in Paris had advised him to rest and entertainment.

He therefore remained in the capital with Jacqueline.

As a child, Blaise had always been sickly.

His sister Gilberte described him as "

worn out by continual illnesses which were always increasing

".

Headaches, excessive heat in the entrails, inability to swallow liquid things other than heated, and drop by drop… These were the usual tortures that woven his daily life.

He never complained about it, but it was a pity to see him pale with pain, his features tense, his face exhausted.

The day after his visit, the great Descartes, who lived at 14 rue Rollin, below the Place de la Contre-Escarpe, had taken the trouble to come back to see the patient.

And had given him plenty of advice on how to recover: stay in bed until he was bored, drink broth, leave his mind fallow.

But can Blaise?

Since his early years, his body has failed him but his mind gallops more than a carriage launched at full speed.

Have fun?

Get dizzy?

Fool around?

Let yourself fall on the soft pillow of doubt and indifference, as Montaigne writes this author whom he loves as much as he exasperates him?

Blaise Pascal, heart and reason

, 164 pages, €13.90, available on newsstands and on

Le Figaro Store

.

Cover after the posthumous portrait of Blaise Pascal by François II Quesnel, after 1662 Figaro-Hors-Série