It is rare to see old books exposed to the public, very old books, incunabula.

Sometimes they appear in museums, temporary exhibitions, shows of one or two months.

But the permanent collections are rare, as if it weren't worth going to, discarding any depth: the paintings can be seen in their entirety from the beginning, but the books... That's why what happens this morning in the Library's treasure vault is so special National Anthropology and History of Mexico City.

A group of 15 people has come together to see an ancient copy, from 1552, exposed for a few hours on a small, visible, breathable lectern.

There are gestures of expectation among those present, of course.

The medium helps.

The vault, an armored room in the basement of the National Museum of Anthropology, suggests mystery and solemnity.

"You have before you," says the master of ceremonies, the director of the Library, Baltazar Brito, "the most important indigenous medicine document of the 16th century."

They all look ahead, at the table with its white tablecloth, an aseptic, hospital image.

On the tablecloth, a rather fine little book, 15 by 20 centimeters, with a wine-colored velvet suit and memories of golden glitter on the edge.

It is not just a medical book.

It is probably the first experiment in literary miscegenation in America.

The

Libellus Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis,

also known as the De la Cruz-Badiano codex, is a miracle of 70 sheets of Genoese paper, lost and forgotten for centuries, rediscovered in the Vatican Library between the wars.

Prepared by two Nahuas of the indigenous nobility who survived the conquest of Tenochtitlan, its content is a testimony of the Mexica past, but also of that present that was beginning to take shape.

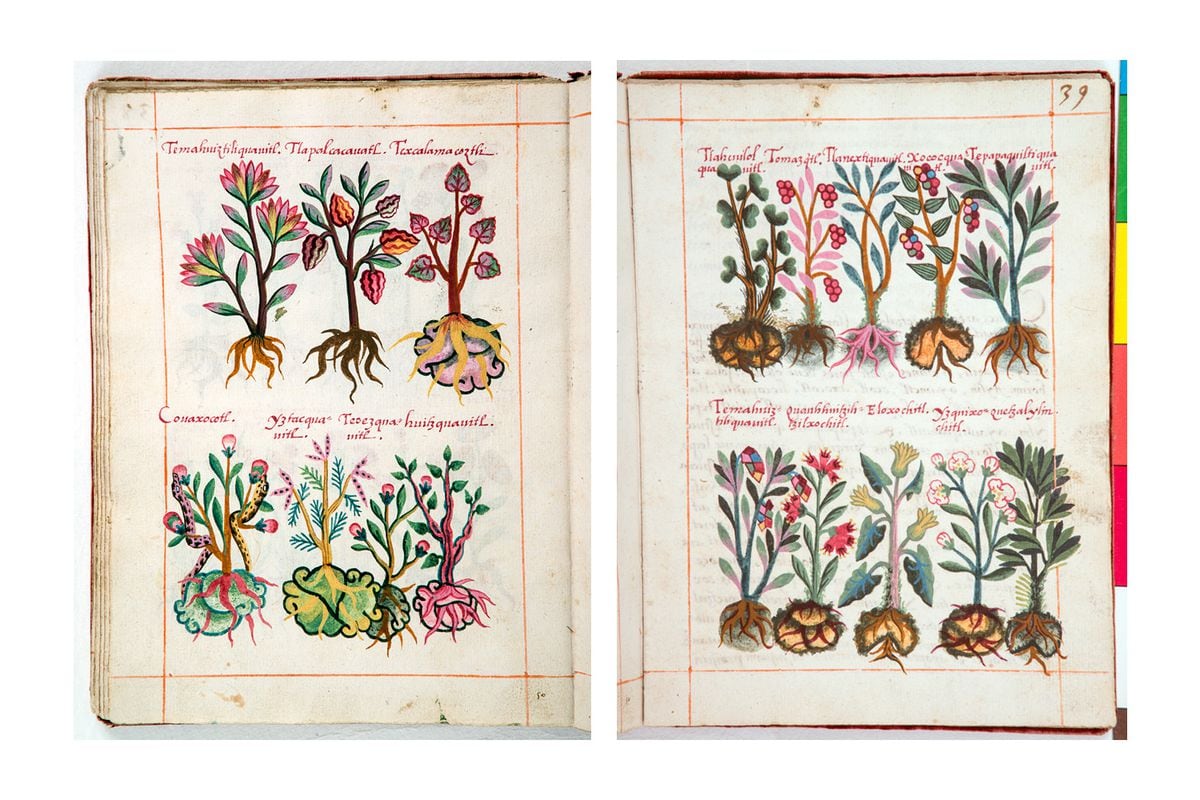

Beautiful drawings of medicinal plants are mixed on the pages with their names in Nahuatl, as well as descriptions of the recipes in Latin, an indicator of their first recipient, Emperor Carlos I. A product for a new era, one of the first delicacies of the New Spain.

The visit to the treasure vault, home to 500 documents, including codices, books, maps and other rarities and delicacies, occurs as a tribute to a new edition of the

Libellus.

The UNAM Faculty of Medicine has just launched its own version of the codex, a little book that faithfully reproduces the original, accompanied by two complementary documents, the Spanish translation by Ángel María Garibay and a collection of new essays on the codex, which shed light on the identity and fate of their authors, the medicinal importance of the recipes, their validity, etc.

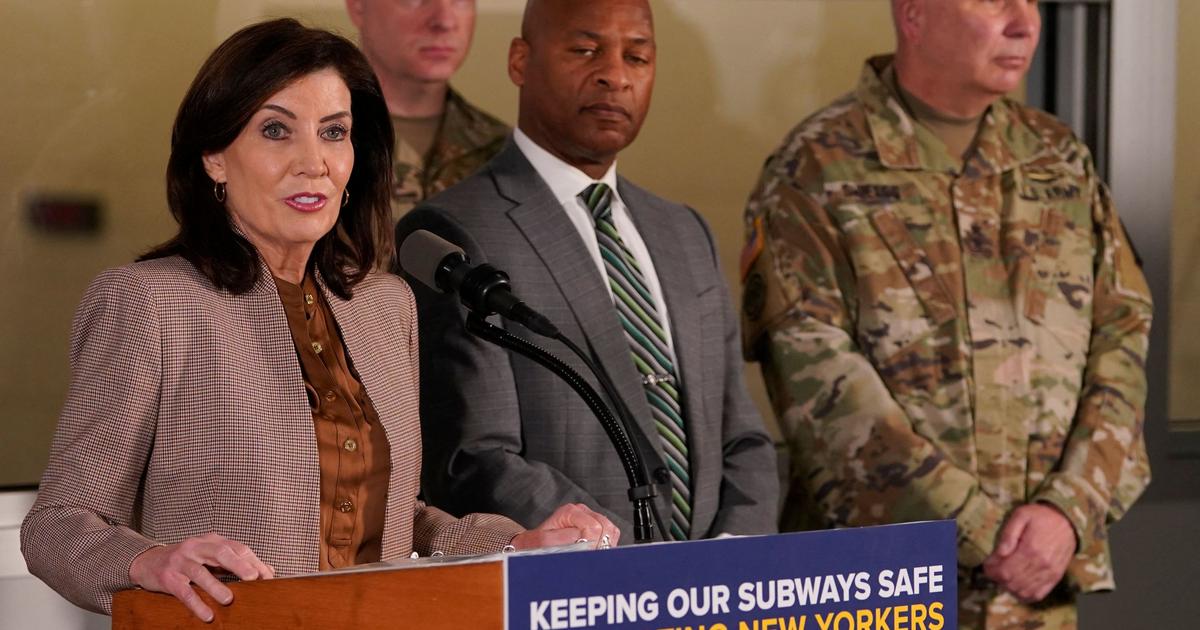

Herbal room of the Palace of the School of Medicine in the Faculty of Medicine of the UNAM, on March 15.

UNAM

The launch of the new edition also accompanies the reopening of the room that the Palace of Medicine, one of the legs of the faculty, has dedicated to the codex for more than 20 years.

Nuria Galland, responsible for the new edition of the

Libellus

and the Palace exhibition, explains that "the walls of the room will collect a selection of 40 species that appear in the codex, preserved in glycerin, and that are still used, with its scientific terminology, its Nahua name, its pre-Hispanic use and its current use”.

It is difficult to find a better site for the exhibition.

The Palace occupies an old house in the historic center of the capital, in front of the Plaza de Santo Domingo.

Built in the mid-18th century, it was the seat of the Inquisition Court for more than 80 years.

Then it fell into disuse, nobody wanted it.

Decades of persecuting witches and heretics left the building gripped with stigma.

Myths and legends of ghosts scared away the most seasoned buyer.

Over the years, the Palace was the seat of the archbishopric, the National Lottery and a military barracks, until, in the mid-19th century, it became the university's medical school.

Today, the Palace rushes its restoration.

The codex room can be visited from the end of March.

A fold-out facsimile will allow visitors to view the contents of the

Libellus

in the exhibition hall, surrounded by the plants it speaks of.

Galland says that "in the end, the exhibition helps to complement the history of medicine in Mexico, the part of ancient Mexico and the miscegenation, when the two worlds come together."

Beware of heresy

An art historian, an expert in the Spanish Baroque and, precisely, in the inquisition, Galland was one of the 15 people who entered the Library's treasure vault to see the original of the Libellus

.

“I was really moved by the intensity of the colors,” she explains.

“No technology can replicate contact with matter.

And I felt that it was reaffirmed with the codex.

There is nothing like the time stamp, the symbolic field around objects”, she adds.

Galland continues with the colors, which he relates to the adventures of the book.

“It is an object that has passed through several hands, through several cities and still exists.

It is testimony to the past, it is fascinating, a wonderful treasure.

The fact that it has such bright colors makes me think that it was not used.

People saw it, they were amazed and that's all, ”he says.

The history of the

Libellus

seems to be taken from an adventure movie from its very gestation.

In the year 1552, in the newborn New Spain, the son of Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza, Francisco, commissioned a book from the College of Tlatelolco to give to King Carlos I, a list of indigenous medicinal knowledge, recipes from the old empire made from of plants, minerals and even animals.

It was an idea, in the Renaissance logic of those times, to incorporate the knowledge of the new territories, but it actually hid a small trap: the recipes had to adjust to the mood of the old kingdom and avoid everything that had to do with the Mexican gods.

Not in vain, part of Mesoamerican medicine had to do with possible anger of their deities, a heresy for the still current inquisition.

The codex, which is stored in the codex vault of the National Library of Anthropology and History.

Dr. Eusebio Dávalos Hurtado (National Library of Anthropology and History)

Francisco De Mendoza's motivation for making a gift to the king is not clear.

Historians and academics have pointed out several possibilities, the first, to win the favor of the monarch and get him to be interested again in the Colegio de Tlatelolco, an educational center for the indigenous nobility, which was struggling to obtain financing.

Another, compatible with the first, is that De Mendoza had a strong interest in obtaining the monopoly to import medicinal plants from New Spain to Europe.

Be that as it may, both things happened over time.

At the College they entrusted the company to the center's doctor, Martín De la Cruz who, according to scholars who have dedicated time to his figure, was born before the conquest, in the 1510s, and trained as a ticitl before the war with the Spanish.

The viceroy and his son must have held him in esteem, because by the middle of the century they allowed him to ride a donkey and carry a crossbow, unusual privileges for the defeated.

As the book was a gift to the king, the order was that it be written in Latin, not in Nahuatl, a language that was also oral, whose transfer to paper was beginning to be invented at that time.

Here De la Cruz received the help of Juan Badiano, a Mexica the same, versed in the use of the language of old Europe.

Said and done, they got down to work and in a short time they handed it over to the viceroy's son.

a traveling codex

It seems that to the old emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, that beautiful little book with the medicinal plants of his new domains, did not say much.

It is unknown if he ever heard of him.

Carlos I was about to abdicate and his son, Felipe, spent time outside before assuming the Crown, at the end of the decade.

Who actually took care of him was the Infanta Juana, Regent of Spain.

Historians assume that she received the codex in the middle of the decade and took it to the Monastery of Las Descalzas Reales, in Madrid.

Already in the monastery, after the years, the codex passed to the domains of Diego de Cortavila, one of the highest authorities in the knowledge of medicinal plants at the time and apothecary of the niece of the Infanta Juana.

By then, Mendoza had already obtained the favor of the regent, who had granted him the monopoly on importing plants from New Spain.

The De la Cruz-Badiano codex remained in the Cortavila library for decades, until, in 1625, the nephew of Pope Urban VIII, Cardinal Francesco Barberini, traveled to Madrid with the task, among other things, of collecting material on plants. medicinal.

One of his assistants visited Cortavila and he showed him the

Libellus.

He bought it instantly and took it back to Italy.

The track is lost, but there is no reason to think that the codex came from the hands of the Barberini, a powerful family at the time.

It is also known that the

Libellus

, as part of the Barberini bibliographic collection, was incorporated into the Vatican Library at the beginning of the 20th century and was there, lost and forgotten, until the researcher Charles Clark found it in 1929. The book was the reason of study and flattery.

New editions were made in Mexico and abroad.

But it was not until 1990, when Pope John Paul II, interested in reestablishing a prosperous relationship with the American country, agreed to return the original.

Since then, the

Libellus

sleeps in the treasure vault of the National Library of Anthropology.

It has ever been exposed to the public, behind a showcase, a total tribute to frustration.

What does one feel when you see a book in a showcase and you can't turn its pages?

As a placebo, the Mexican government digitized the codex, like many others, and today it can be consulted in its entirety on the Internet.

subscribe here

to the EL PAÍS México

newsletter

and receive all the key information on current affairs in this country

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/2C5HI6YHNFHDLJSBNWHOIAS2AE.jpeg)