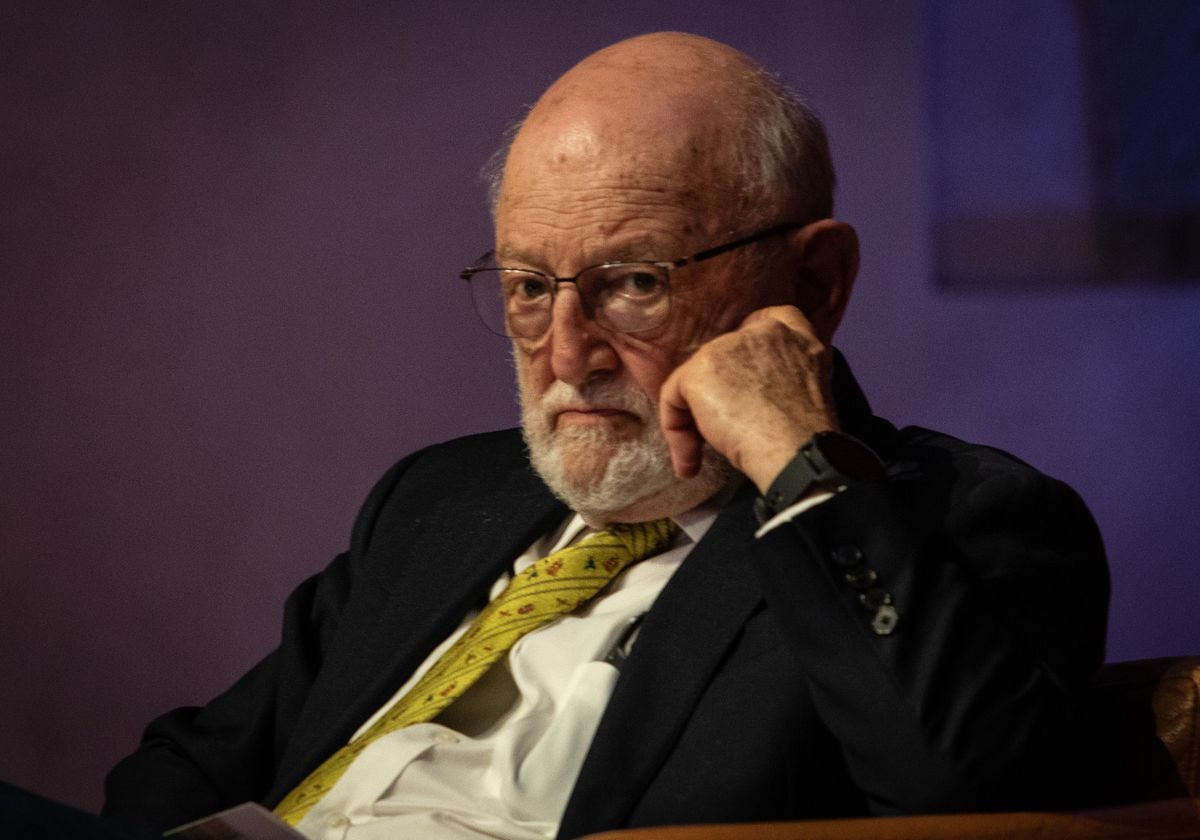

José Antonio Alonso. Ceded by the author

The doctor in Economic Sciences and professor at the Complutense University of Madrid, expert in development cooperation, José Antonio Alonso (1953), received a commission from his "old friend" José Luis García Delgado: to give three master classes on child poverty in the Chair in Economy and Society, at the laCaixa Foundation.

Alonso accepted the invitation and gave the conferences in September 2021. But he did not stop investigating a topic that, despite his extensive experience in the development sector —has been a member of the UN Development Policy Committee and a member of the Advisory Committee of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation in Europe, among others—had barely occupied his schedule.

His latest title,

El futuro que inhabita entre nosotros

(Galixia Gutenberg), was born from his inquiries, which he presented this Tuesday at the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation (AECID), accompanied by authorities in the field such as Carmen Gayo, director of the High Commissioner against Child Poverty or José María Vera, director of Unicef Spain.

During the writing of his book, Alonso discovered that "public policies have an anti-child bias that does not correspond to the discourse."

To a large extent, he says, because children don't vote.

Ask.

Despite his extensive experience in cooperation, what has surprised you about his research to write this book?

Answer.

We always say that poverty is not only about income, but in reality, the data is basically about income.

There is a poverty derived from the violation of the right to affection and protection.

I am talking about abandoned children, without an environment of protection and guardianship, without that nucleus of affection that is necessary for the development of the person.

The second thing that I had not considered is the issue of the voice and representation of minors.

I began to find that public policies have an anti-child bias that does not correspond to the discourse.

Q.

In the book you take a tour of child poverty in history.

What is the current photograph?

R.

Despite the progress during the last period, the child poverty data has improved little.

It has fallen fundamentally because China and India, which had very high volumes of population below the poverty line, lifted a good part of the population out of that situation.

But we continue to find that for every two poor people in the world, one is a minor.

And child poverty is higher than general.

This happens in the developing world and in most OECD countries.

The countries in which this phenomenon does not occur are those that have implemented social policies more clearly aimed at combating child poverty or improving the well-being of minors.

Child poverty, somehow, launches the accusatory gesture more than any other type of poverty, not to those who suffer from it, but to the rest of society

Q.

The High Commissioner against Child Poverty calculates that this problem costs Spain more than 63,000 million euros a year and that more investment in combating it would reduce that cost.

Should we care more about stopping it for this alone?

R.

It should matter to us because it is not just another poverty.

It generates effects that are long-lasting over time and conditions the future lives of people.

There is another moral reason, of social responsibility.

Child poverty, in some way, launches the accusatory gesture more than any other type of poverty, not to those who suffer from it, but to the rest of society, because we have the obligation of their guardianship and protection, and we are failing to comply.

There is also a practice.

The fight against child poverty is the best investment in terms of social return.

It not only allows us to grow, but also avoid costs in terms of health, violence, crime, etc. and, ultimately, build a more prosperous society.

Condoning child poverty is not only a form of injustice, but it is also a form of collective idiocy.

P.

However, you defend that children should not only matter to us because of the adult they are going to be.

R.

When I reflected on the title, I had a doubt: childhood is often talked about without giving value to what children are, but thinking about what they are going to be as power.

And I would not want to transfer that idea.

I don't think we have to combat child poverty because that places us better in the future.

You have to fight it because they are suffering from it right now and it disables them to have a happy life.

It is important not only to see in childhood the power of the adult that is going to be.

Children have vital aspirations and illusions.

Q.

Do you think there is a paternalistic vision?

R.

The tendency is to fall back on a paternalism that we should discard.

It is one thing for us to recognize that we have a special responsibility with minors and another to think that they do not know what they want to do and not even consult them.

The minor must be considered not only as a subject of protection, but as a being capable of influencing the reality that affects him.

But there is a lot of hypocrisy, precisely because childhood generates weak consensus.

No one is against it supporting children, but that does not translate effectively into policy.

Most countries are consistently achieving higher gains for adults than for children.

It is very clear that it is because adults vote and influence and minors do not.

We must combat child poverty because they are suffering from it right now and it makes them unable to have a happy life

Q.

Should minors vote?

R.

I don't have a clear opinion, but I think we should discuss it.

We would have to open this debate, which in Spain does not occur as in the United States and the Nordic countries.

One option is that a minor who expressly requests it can exercise her vote.

The fact that he asks to vote already implies a certain maturity, it shows that he is concerned about what is happening.

There is the alternative of lowering the age to 16, but I don't know if a defined time limit is the best way to solve the problem.

Q.

How would that contribute to reducing poverty?

R.

There would be a greater concern of the political parties for the interests of minors.

Public policies are built based on pressure from different groups to impose their interests.

The fact that minors could exercise this active pressure would help the policy to give them greater relevance.

Today their only way of influencing public policy is through their parents, but there is a lot of mediation there.

It would help to enrich democratic life, to train citizens because from a very young age they would be concerned about expressing their opinion, and it would build more balanced public policies.

I understand that it generates many problems and has many drawbacks that should be studied.

No one is against it supporting children, but that doesn't translate effectively into policy

Q.

What lessons can sub-Saharan African countries, where the problem is concentrated today, learn from China and India?

R.

That employment is the first pillar to combat child poverty.

One of the reasons why Spain has a higher incidence of child poverty than the rest of Europe is because unemployment rates and job instability are much higher.

Full employment in formal jobs supplies families with income.

It is an avenue that China actively used.

It is a mechanism that developing countries in Africa should learn.

On many occasions, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and even donors encourage growth models more oriented towards competitive advantages in international markets than the generation of a mass of entrepreneurial initiatives from the country itself.

That should be corrected.

Q.

The face of poverty in the world is that of an African girl. Does the fight against child poverty have to have a gender perspective?

R.

The gender perspective is basic and must be incorporated from the diagnosis.

If you look at the child labor data, about 60% are boys.

But the reality is that domestic work is not counted, the one that the girl does inside the home.

It is important to make the girl visible because in many cases the statistics simply do not appear.

You can follow PLANETA FUTURO on

,

and

, and subscribe

here

to our 'newsletter'

.