SOYAPANGO, El Salvador - When the

gang MS-13

ran the Las Margaritas neighborhood, one of their strongholds in

El Salvador

, there were rules you had to follow to stay alive.

You couldn't wear the number eight because it was associated with the rival gang on 18th Street. You couldn't wear the brand of sneakers that gang members wore.

And you couldn't, under any circumstances, call the police.

During the government crackdown, gang graffiti was covered in white paint.

Photographs by Daniele Volpe

"People couldn't complain to the police about what the kids would say," says longtime resident Sandra Elizabeth Inglés, referring to the gang members.

"They became the authority of this system."

El Salvador, the smallest country in Central America, was once known as the

murder capital of the hemisphere

, with one of the highest murder rates in the world outside of a war zone.

But in the year since the government declared a state of emergency to quell gang violence and deployed the army on the streets, the country has undergone a

remarkable transformation.

Now, children play soccer late into the night on fields that were once gang territory.

Inglés collects soil for his plants next to an abandoned building that residents say was used for gang killings.

Now children can play on soccer fields previously controlled by gangs.

Photographs by Daniele Volpe

Homicides have dropped.

Extortion

payments

imposed by gangs on businesses and residents, once an economy unto themselves, have also declined, according to analysts.

"You can walk freely," said English.

"A lot of things have changed."

El Faro, the main media outlet in El Salvador, conducted a survey in the country earlier this year and offered a surprising balance:

Gangs, to a large extent, "don't exist."

But that achievement, critics say, has come at an incalculable price:

mass arrests that wiped out thousands of innocents, the erosion of civil liberties, and the country's descent into an increasingly autocratic police state.

Before the crackdown, no one visited the area's main open-air market without permission from the gang that controlled it.

Now come who wants.

Photographs by Daniele Volpe

Most Salvadorans seem willing to accept that deal.

Fed up with the gangs that terrorized them and forced so many to flee to the United States, the vast majority of the population

supports the measures

and the president who backs them, polls suggest.

With

approval ratings hovering around 90%,

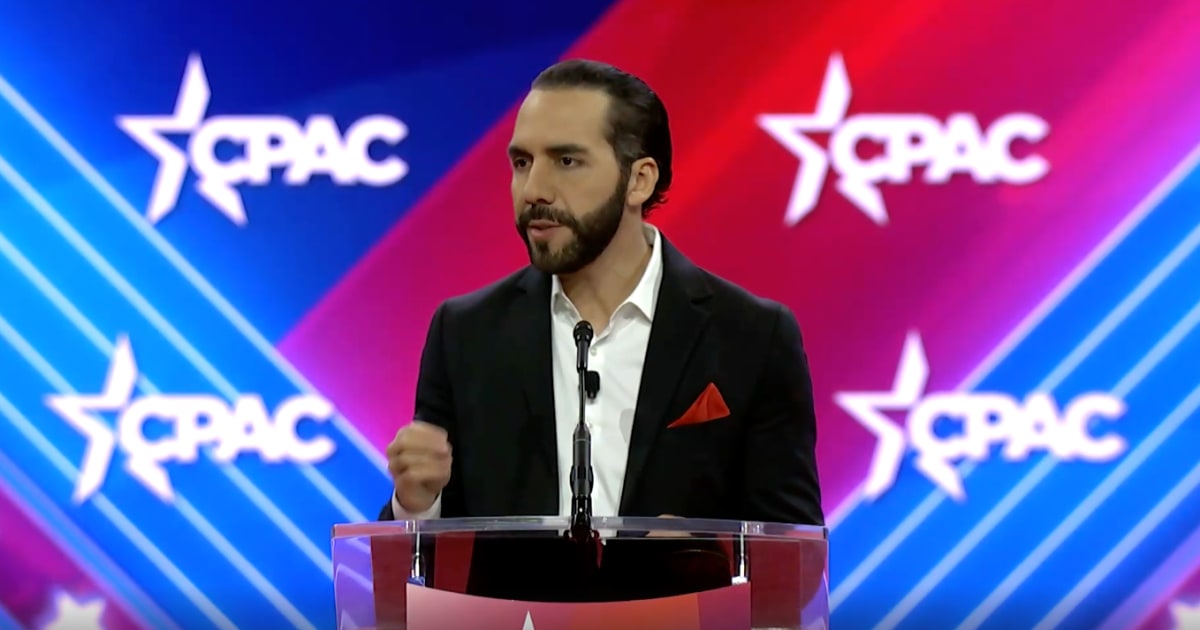

El Salvador's President

Nayib Bukele

, 41, has become one of the world's most popular leaders, winning fans across the Western Hemisphere.

Hondurans chanted Bukele's name and cheered him at the inauguration of their president last year.

A survey revealed that Ecuadorians, where violence is on the rise, think better of Bukele than of their own leaders.

As politicians in

Mexico and Guatemala

vow to emulate Bukele's heavy hand, critics fear the country could become a dangerous negotiating model:

sacrifice

civil liberties

for security.

The Vice President of El Salvador, Félix Ulloa, in his office in San Salvador.

"We have returned freedom to the people," he said.

Photographs by Daniele Volpe

"I remain incredibly pessimistic about what this means for the future of democracy in the region," said Christine Wade, an expert on El Salvador at Washington College in Maryland.

"The risk is that this becomes a popular model for other politicians to say: 'Well, we could provide you with more security in exchange for you giving up some of your rights.'"

The Salvadoran government has

detained more than 65,000 people

in the past year, including children as young as 12, more than double the total prison population.

By the government's own count,

more than 5,000 people

with no connection to the gangs were jailed and eventually released.

According to the government, at least 90 people died in custody.

Human rights groups have documented mass arbitrary detentions, as well as

extreme overcrowding in prisons and allegations of torture

by guards.

El Salvador's Vice President,

Félix Ulloa,

said in an interview that allegations of abuse by authorities were being investigated and innocent people who had been detained were being released.

The neighborhood of La Campanera, in the municipality of Soyapango, near the capital of El Salvador.

The neighborhood was once controlled by the Calle 18 gang. Photographs by Daniele Volpe

"There is a

margin for error

," he said, defending what he called an "almost surgically flawless" strategy.

"People can go out, buy things, go to the movies, to the beach, watch soccer games," he said.

"We have returned freedom to the people."

In what were once some of the most dangerous areas of the country, abandoned houses that belonged to gang members are being

renovated and reoccupied

with new tenants.

On the streets of

Las Margaritas

, a neighborhood in the once horribly violent Soyapango municipality in the center of the country, cars now park without their owners paying $10 a month to extortionists from the gangs.

Sandra Elizabeth Inglés at her juice stand, not far from her home in Las Margaritas.

She says that before, the gang members were the authority in the town.

Photographs by Daniele Volpe

Before the crackdown, no one visited the municipality's main open-air market without permission from gang henchmen, according to vendors.

Now it overflows with whoever wants to be there.

When Inglés told people where he lived, on a cul-de-sac in Las Margaritas, their jaws dropped.

"They told me: 'Oh, no, if you live in Vietnam,'" recalls Inglés, as he serves mango juice in a bag to a child at the stand he runs in front of his house.

I used to stare across the street at graffiti that read "see, hear and shut up," says Inglés, a phrase used by the gang to intimidate residents into keeping quiet about their crimes.

Abandoned homes previously occupied by gang members before being detained over the past year.

Some of the original owners, who left because of gang threats, are beginning to return.

Photographs by Daniele Volpe

English says that he learned to bow his head:

"The less things you saw, the less problems you would have."

The image of a bird was recently painted over the graffiti.

Juan Hernández, 41, had

not stepped foot on a soccer field located a few blocks from his house

for 10 years .

"It was grass," he said, referring to gang territory.

"The bullets hit you left and right."

Now he uses the field to teach his 12-year-old son to play.

"He tells me that I want to learn, I tell him, let's go," Hernández said.

The catalyst for the new reality emerging in El Salvador was a weekend of criminal rampage in March of last year that left more than

80 people dead.

Abandoned homes previously occupied by gang members before being detained over the past year.

Some of the original owners, who left because of gang threats, are beginning to return.

Photographs by Daniele Volpe

US officials have claimed that long before the crackdown, the Bukele government

negotiated an agreement

with gang leaders to reduce homicides in exchange for benefits, including better prison conditions.

Many analysts believed that the uptick in violence was a sign that the alleged pact had broken down;

Bukele has denied having reached such an agreement.

Following the March killings, El Salvador's legislative assembly, controlled by the ruling party, declared a state of emergency.

The army flooded gang areas across the country and arrested 13,000 people in a few weeks.

Soldiers patrolling one of the main highways in Soyapango, El Salvador.

Photographs by Daniele Volpe

One of them was the son of Morena Guadalupe de Sandoval, whom he says he has not seen or spoken to since he was detained on his way back from work in the capital about a year ago.

She says that the authorities have accused her of being part of a criminal group, something she denies.

Every three months he visits the Izalco prison, where he says his son Jonathan González López is being held, a center in the west of the country where torture has been reported.

Ask for information about him.

He sometimes takes his wife and his two-year-old son.

The most he hears is that

he is still locked up.

"Depression takes over," says de Sandoval.

"I get terrible when I think about how I can't see him or talk to him."

In a report published in December,

Human Rights Watch

and a Salvadoran organization called Cristosal interviewed people detained during the crackdown who were later released, describing the horrors they witnessed inside the country's prison system:

beatings, deaths, starvation rations.

One of them claimed that guards were holding his head under water "so he couldn't breathe," according to the report.

Another said that they gave him two tortillas to eat a day, which he had to share with another detainee.

De Sandoval says the crackdown has improved things in his neighborhood, an area called the Italian District that was once dominated by MS-13.

He does not see young people smoking in the street.

She says that she no longer sees young people smoking pot on street corners.

"It's safer," he says.

"In that sense, it's a good thing."

But he can't separate the positive side from his daily pain.

Her son will turn 22 "on the inside" this month, she says.

She dreams of seeing him just once.

"I just want to see it," de Sandoval said, "even if it's from afar."

c.2023 The New York Times Company

look also

Bukele shows a path... wrong

Prisons disguised as shelters: the background of mistreatment behind the tragedy in a migrant center in Mexico

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/KMEYMJKESBAZBE4MRBAM4TGHIQ.jpg)