On March 30, several men from Russian intelligence services approached American journalist Evan Gershkovich in a restaurant in the Ural city of Yekaterinburg, where the Wall Street Journal correspondent had been working on another article on the

war

. of Russia in Ukraine.

They put a cloth over his head to get him out of the premises and took him into custody, according to several witnesses quoted by the independent local press.

Hours later, Gershkovich, 31, was transferred to Moscow on espionage charges.

The arrest, which has brought the situation in Russia back into focus, could have been one of many stories Gershkovich would have covered in a country that persecutes independent journalism, tries to control the media and sows noise. the international information space to dilute the lies between the truth and where reporting the reality —and more about the Russian invasion of Ukraine— poses a risk;

especially for Russian journalists.

Gerschkovich remains in pretrial detention in Moscow's infamous Lefortnovo prison.

He is the first American reporter to be jailed on espionage charges in modern Russia.

The last such case was in 1986, when Nicholas Daniloff was arrested in the Soviet Union.

The

Wall Street Journal journalist,

son of a Jewish couple who emigrated from the Soviet Union to the United States, and who arrived in Moscow a few years ago, where he had worked for

The Moscow Times,

the AFP agency,

The New York Times

and

The Wall Street Journal

, documented the increasing repression of the Putin regime.

“Reporting on Russia now also standard practice seeing people you know locked up for years,” the reporter tweeted in the summer.

Dmitri Peskov, a Kremlin spokesman, claimed just a day after his arrest that the journalist had been caught "red-handed."

A quick reaction that is another sign that the Kremlin managed together with its intelligence services (in this case the FSB, heir to the KGB) the arrest of the American, according to a Western intelligence official who has worked for years in Russia.

The spokeswoman for the Russian Foreign Ministry, Maria Zajárova, also launched a veiled threat against other informers after Gershkovich's arrest.

“Unfortunately, this is not the first time that 'foreign correspondent' status, journalistic visa and accreditation have been used by foreigners in our country to cover up non-journalistic activities,” she charged.

“It is not the first time that a Western acquaintance has been caught

red-handed

.”

Gershkovich was accredited as an international correspondent in Russia, a credential for which approval must be obtained from the Foreign Ministry and which is far from immediate.

In addition, accredited correspondents are under the umbrella of "tutors" from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs who follow their work and there is a large bureaucratic network that collects data from foreign reporters: from the residence registration to annual medical tests.

The Wall Street Journal

, which has campaigned hard to free its reporter, has "vehemently" denied all the charges.

The US State Department has declared Gershkovich "unfairly detained," a label that broadens the pressure tools for his release.

And the president of the United States, Joe Biden, has assured that the arrest is “totally illegal”.

His case has caused a wave of outrage and solidarity among Western governments, human rights organizations and the media around the world, who have demanded the Kremlin for his release.

Also, among Russian independent journalists.

Dozens of them, such as the Nobel Peace Prize winner Dmitri Muratov, have signed a letter criticizing Russian espionage services and their attacks on press freedom in which they demand Gershkovich's release.

Arsenal fans unfurl a banner in support of Evan Gershkovich at a match at London's Emirates Stadium on Friday.JOHN SIBLEY (Action Images via Reuters)

15 years in prison for reporting on the invasion

Just days after Russia invaded Ukraine, 14 months ago, the autocratic government of Vladimir Putin passed a law that threatens up to 15 years in prison for anyone who publishes information about the invasion that the authorities consider false and threatens charges against those who call war to what the Kremlin calls a "special military operation."

And to this it has been adding other rules to make it difficult to report on the war in Ukraine.

About twenty journalists remained in prison in Russia in December 2022, according to data from the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

Russia is ranked 155 out of 180 in the Reporters Without Borders press freedom index.

The Eurasian country, where not a few cases of journalists attacked and assassinated have been recorded and in which the Kremlin has spent years harassing the free press and moving so that like-minded businessmen take control, one after another, of the non-state media, is traditionally at the bottom of the scale.

Many foreign correspondents - mainly Anglo-Saxons - left Russia with those repressive laws in the early stages of the invasion and some others suspended their activities in the country for weeks.

But most of the remaining international reporters have continued to define the war for what it is, albeit with even less access to official information and with the knowledge that access to independent sources puts them at risk if they are not taken. appropriate measures to protect them.

The reality is that the authoritarian drift against the free press has been focused on Russian informants for years.

Like the case of Maria Ponomarenko, sentenced to six years in prison by a Siberian court for writing a comment on social networks about the Russian attack that killed hundreds of people who were taking refuge in the Mariupol Drama Theater, in Ukraine.

Or that of Ivan Safronov, sentenced last year to 22 years in prison on charges of high treason that human rights organizations have defined as false.

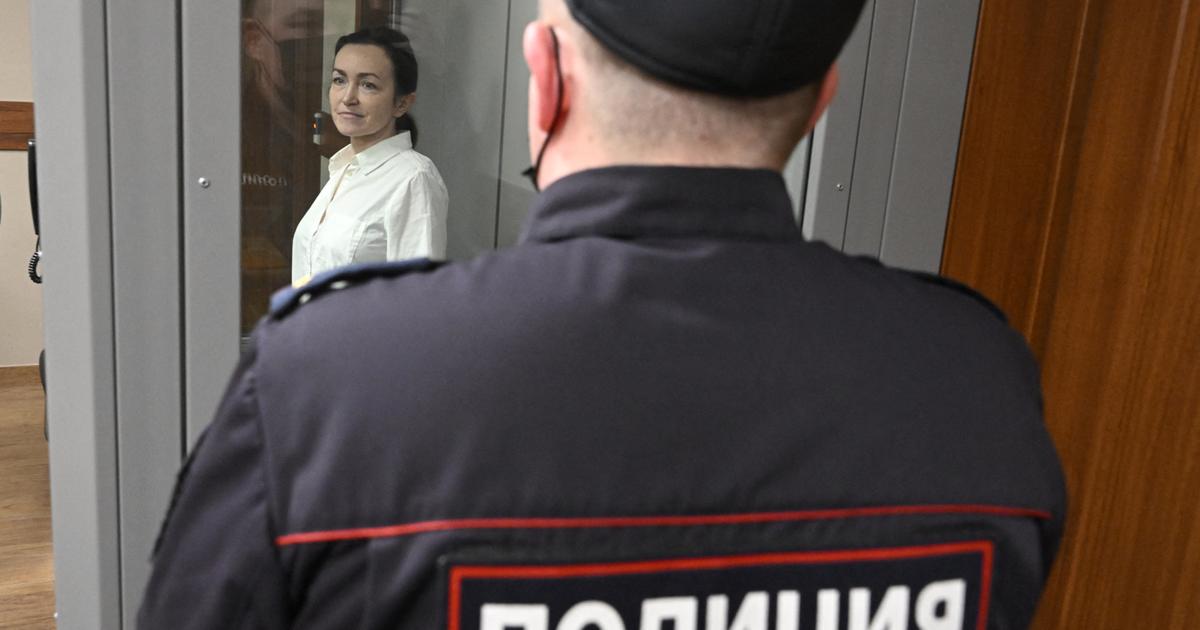

Russian journalist Maria Ponomarenko at a court hearing.amnesty international

“Only Russian citizens can be arrested for treason, while espionage charges are reserved for foreigners,” says Ksenia Mironova, a journalist for the independent

Dozh

outlet and Safronov's partner.

In an op-ed in

The Moscow Times,

Mironova notes that the Russian authorities can find a way to imprison anyone, although being charged with espionage or treason is "a particularly hard pill to swallow."

The Russian authorities have long made an elastic interpretation of the laws.

Espionage cases are often handled undercover, but it can mean anything from collecting information (public or not) for a foreign organization that the Kremlin believes threatens its security to actually working as a spy.

The repression has also worsened so far this year.

OVD info, a human rights organization that fights against political persecution, has counted 10 cases of accusation of espionage and treason in the month of March alone;

among them that of the journalist Gershkovich.

The organization's lawyers explain that the number of people sentenced to prison for war-related charges is increasing, although the figures are not specific, since many trials are secret.

The International Press Institute (IPI) has documented more than 600 threats or violations of press freedom in Russia since the start of the war, including more than 300 cases in which journalists and media outlets have faced fines, publication bans or other administrative measures for reporting on the war, according to an IPI report.

Since the start of the invasion of Ukraine, more than 260 publications have been closed, blocked or canceled in Russia, according to reports in

Novaya Gazeta

, the independent daily run by Nobel laureate Muratov whose license was revoked by Russian authorities last year.

What happened with Gershkovich shows two legs of the reality of Russia.

On the one hand, it is the umpteenth attack on press freedom, a warning to Russian and foreign journalists that no one is safe.

On the other, it is yet another example of the Kremlin's habitual use of a hostage-taking policy to put pressure on groups, entities or governments and, on many occasions, exchange them for their own nationals, analyst Tatiana Stanovaya points out in a commentary.

As in the case of the American basketball player Brittney Griner, who was arrested for possessing cannabis oil and was exchanged for the Russian arms dealer Viktor Bout.

The arrest of

The Wall Street Journal

correspondent came as a shock to many Russian colleagues, acknowledges Anna L., who reports on Russia on a Telegram news channel and prefers to hide her last name for fear of reprisals.

The journalist is still in the Eurasian country, from where many of her colleagues have left due to persecution by the authorities.

The Russian-language

online

outlet Meduza, founded in Latvia and one of the best-known inside Russia, was declared an “undesirable organization” two months ago, making it difficult for it to access sources, readers and donors.

One after another, independent media outlets, large and small, have had to close or relocate their newsrooms abroad.

Or dissolve "in the most anonymous way possible" in the virtual space of Telegram, says the journalist, where the Russian citizens fleeing from the propaganda diet broadcast by the Kremlin-based media are reported.

Few believed that the Russian government would act in this way, with a charge as serious as espionage, against someone from a foreign milieu.

Follow all the international information on

and

, or in

our weekly newsletter

.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/76L5X4IKAWC2ED6MX6LOFYLCBI.jpg)