At the end of the Bogotá book fair, a reader in her seventies wanted to know my opinion about the news we had just received: an unpublished novel by García Márquez will be published next year.

This is

En agosto nos vemos

, a manuscript that many of us had already heard about: García Márquez spent several years thinking about the story, and even read some pages of an early incarnation in a very rare public appearance, but he did not manage to finish it. before his memory was ravaged by illness.

This novel was one of the last attempts he made to overcome his own limitations;

but, although he managed to finish his memoirs and a short novel in the last years of his life, the final form of

See You In August

he kept escaping.

Writing fiction, and especially that very demanding form of fiction that is a fairly complex novel, is impossible without memory.

Well, the reader at the fair was of the opinion that the novel should not be published.

If García Márquez never published it, if he didn't finish it because he didn't know how to do it, do we have the right to know about it?

Isn't that violating the will of the writer?

This reader had been outraged by the serial imbecilities recently committed by English-language publishers against the books of people like Roald Dahl or Agatha Christie or poor Ian Fleming, and she asked me why, if we reject these attacks on the words of an author who can no longer defend them, it will seem good to us that what an author did not give to the press be published.

It seemed like an intelligent argument to me;

and the simple fact that this woman took the side of the dead authors, and therefore against the nonsense that reigns in our world, I found touching,

and I would have gladly agreed with him.

But in this case I couldn't do it: because the news about the publication of

See you in August

had filled me with intimate joy, and it would have been hypocritical to say anything else.

Yes, I am grateful that this novel is published.

Although it is incomplete, although García Márquez has not been able to finish it, although he has not given authorization for it to come to light.

I told the reader that precisely because of all these deficiencies it was up to us, the readers of García Márquez, to know how to read a similar book: to know while we read that it is not definitive, and therefore does not belong to the same order of things where the novels that García Márquez published in life exist.

In other words, it is up to us to adjust the reading glasses;

but it would never seem preferable to me to be deprived of contact with the unfinished work of a great artist.

I'm not going to talk about the affection I have for Michelangelo's draft sculptures,

Precisely because they are half done, they allow us a wonderful window that directly overlooks the workshop.

Let us confine ourselves to literature to say what I said when a novel by Hemingway appeared almost rewritten by his son, for example, or that novel by Louis-Ferdinand Céline: the lost work of an anti-Semite who, apart from being an anti-Semite, was a writer. enormous.

In all those cases I said the same thing that I say in this one: give me the book, and I'll decide how to read it.

I don't think the same is true for everyone.

But García Márquez is not everyone: he is a writer who forever transformed my way of relating to my country, and also, along with seven or eight other writers, he transformed our language, our tradition, and the culture of our Latin American continent.

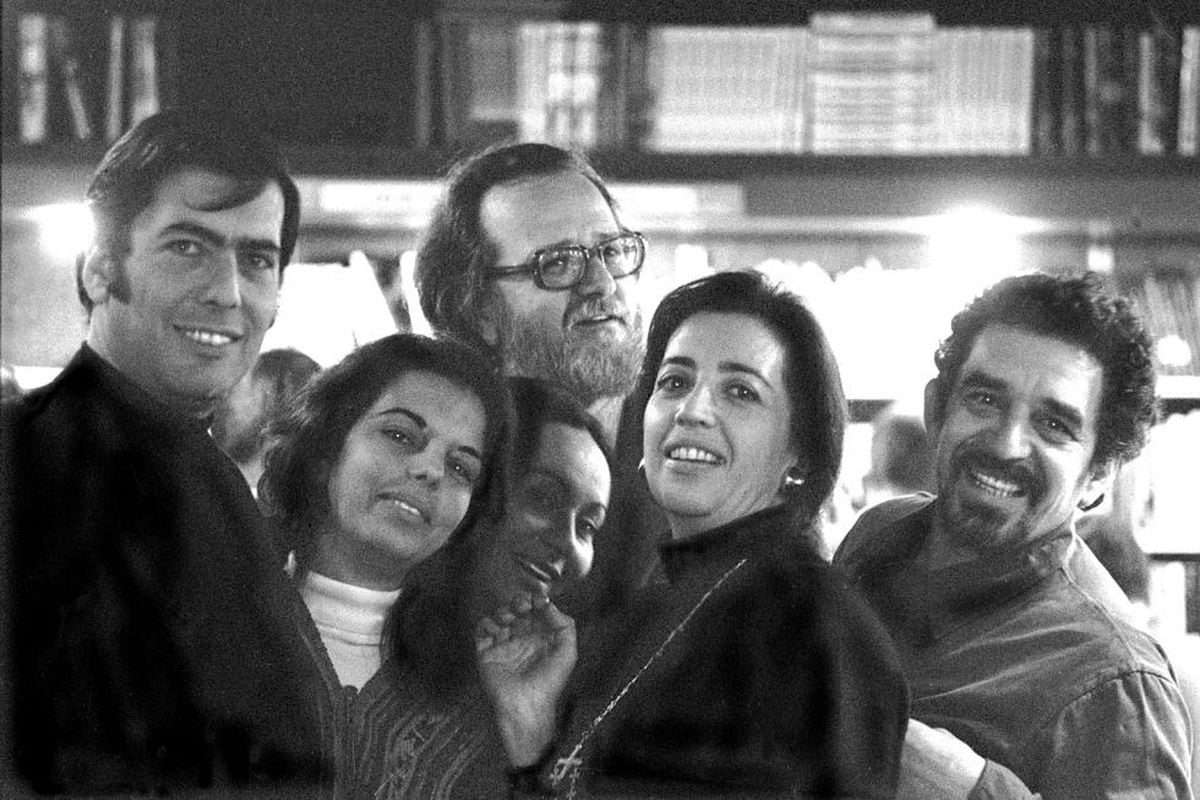

I've been thinking about that frequently these days, because all of that was more or less sixty years ago: what we now call the Latin American boom began more or less then.

But when, exactly?

Some say that it was with the publication of

La ciudad y los perros

, the novel by a very young Peruvian, who had received the Biblioteca Breve prize in the last weeks of 1962.

Others, that it was with the extraordinary coincidence in the space of a few months of

The Century of Enlightenment

,

The Death of Artemio Cruz

and

Hopscotch

, which appeared in mid-1963. Literary historians have written ad nauseam about this phenomenon, but they still cannot agree on the precise moment when what exploded broke out.

And what was that?

What was it that started?

Certainly not Latin American fiction, which had produced a handful of outstanding works in the first quarter of the century and had been inventing marvels since at least the 1940s: when Borges published

Ficciones

and

El Aleph

.

Miracles from the 1950s include

La vida breve

, by Juan Carlos Onetti, and

Pedro Páramo

, by Juan Rulfo;

By the time that very young Peruvian received the prize of yore, the stories of

Bestiario

and novels

The Most Transparent Region

and

The Colonel Has No One to Write to Him had already appeared

.

So it is not that the universe was created where before there was only a dark void, as so many clueless readers of those years believed.

And yet, by early 1963, people were realizing that something was happening for the first time, or that something was transforming in such a noticeable way that it was hard not to give in to the impression of the foundations.

I am the son of that transformation.

And those books are part of the mental landscape of any of you, readers of my language, and we talk about them as we talk about the classics, because that's what they are without a doubt.

What's more: those writers and those novels have become such daily presences, and we have become so used to their company, that it is easy to forget the profound revolution that they constituted then.

I have said a thousand times that I would give anything to read

One Hundred Years of Solitude

again for the first time: this has to be the greatest frustration of every dedicated reader, for it is really the only impossible desire: you never rediscover what you already know. has discovered.

Actually, my biggest wish would be to read

One Hundred Years of Solitude.

for the first time, but also doing it in 1967, in the world where the novel appeared to everyone's surprise, in the world that turned the novel upside down and where its title began to pass from mouth to mouth with the speed of slander.

Perhaps all of this that I have written is nothing more than an elaborate way of thanking the future publication of

See You in August

: thanking that I, who have grown as a reader and novelist in the world where these names have published their books, allow me to continue having the immense pleasure –or the privileged discovery– of his unknown books.

I was barely a child when Cortázar died and an adolescent when Borges died, but the death of Fuentes and that of García Márquez surprised me with full awareness of the emptiness that will open before us when the last of the generation, Vargas Llosa, is no longer around. .

A writer dies twice: when he dies and when we stop reading him.

And I don't want the writers I care about to continue dying after death.

Juan Gabriel Vásquez

is a writer

Subscribe here

to the EL PAÍS newsletter on Colombia and receive all the latest information on the country.

Subscribe to continue reading

Read without limits

Keep reading

I'm already a subscriber