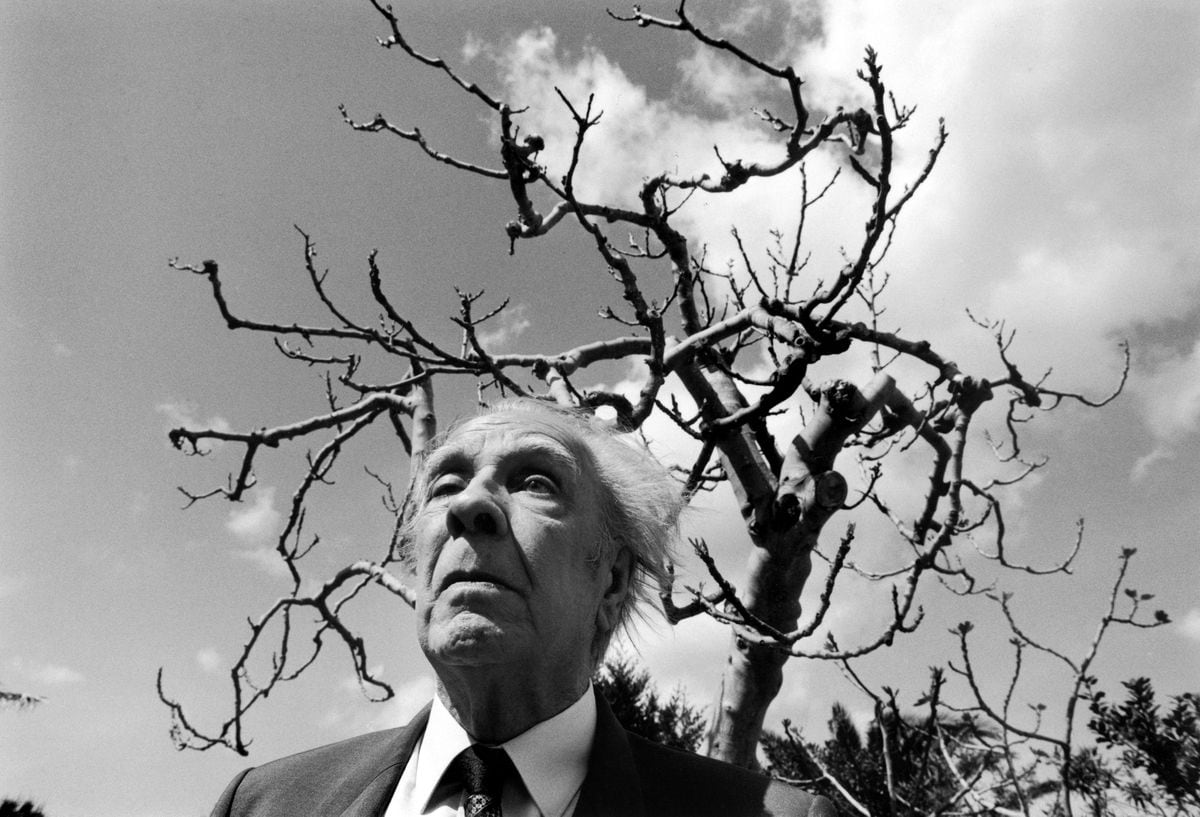

Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges in 1984, during a trip to Sicily.Ferdinando Scianna (Magnum Photos / ContactoPhoto)

In general, when people talk about memory it is to refer to forgetting rather than memory: "I have a very bad memory", "I forget everything", are exaggeratedly frequent expressions. I think it is a reality that almost everyone has assumed a kind of axiom that would go like this: "Remembering is good, forgetting is bad." However, without forgetting nothing would go well, neither our memory nor, of course, our life. We have just seen how forgetting facilitates memory and how, in general, it is essential for an effective functioning of memory. Forgetting is necessary, William James made it clear when he warned that if we remembered absolutely everything we would have as bad a time in life as if we remembered nothing.

More information

Our brain is not like a computer

I think Borges understood like no one else the curse that would be to have a memory that kept and remembered everything. In his brilliant and splendid story Funes el memorioso, Borges draws with perfect prose the portrait of a boy who, after being "turned over by a redomón", was crippled and without hope of recovery. The story becomes fascinating from the moment of the fall, because that nineteen-year-old gaucho, who "had lived like one who dreams: he looked without seeing, heard without hearing, forgot everything, almost everything", now had a prodigious, infallible memory. The fall of the horse caused him to lose consciousness, but when he regained it "the present was almost intolerable of so rich and so sharp, and also the oldest and most trivial memories." Funes, surprisingly, does not lose his memory when he is "flipped" by a horse, but oblivion and, thus, the genius of Borges turns a badly wounded boy hit in the head into a superior being, into "a maroonish and vernacular Zarathustra" with an overwhelmingly accurate memory. (...)

Funes remembers everything, forgets nothing. He can't forget anything. "What he thought once could no longer be erased." Funes is a human being captive to an implacable memory that cannot be forgotten. "I didn't just remember every leaf on every tree on every mountain, but every time I had perceived or imagined it. (...) He continually discerned the advances of corruption, cavities, fatigue." (...)

Such a human being, immersed in his own vertigo, tied to details, incapable of general ideas, incapable of thinking, because "to think is to forget differences, it is to generalize, to abstract", a superman, a Zarathustra, is born in the mind of Borges influenced, no doubt, by the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche, one of the philosophers reread by the Argentine writer; specifically, from the passage of the work On the usefulness and harm of history for life, where the German philosopher declares the vital need for oblivion with these words: "Imagine the extreme case of a man who had been completely dispossessed of the strength to forget, someone who was condemned to see everywhere a becoming. Such a man would no longer be able to believe in his own existence, for he would see all things flow separately into movable points. It would thus be lost in this current of becoming. Like that consistent disciple of Heraclitus, he will scarcely dare to lift a finger. And it is that in every action there is forgetfulness, in the same way that the life of every organism not only needs light but also darkness. (...) It is possible to live almost without memories, and even to live happily, (...) but it is impossible to live without forgetting."

We need to forget. Although we complain about forgetting, life, as Nietzsche emphasized, is not possible without forgetting. Forgetting is much more necessary than we imagine. Memory scientists don't hesitate to claim that forgetting is exactly what our memory needs to function optimally. In his best-known and most influential work Les maladies de la mémoire (The Diseases of Memory), the French psychologist Théodule Ribot (1839-1916) stressed the value and necessity of forgetting. In his own words: "(...) One condition of memory is forgetfulness. Without the total forgetfulness of a prodigious number of states of consciousness and the momentary forgetfulness of another great number, we cannot remember. Forgetting, except in certain cases, is therefore not a disease of memory, but a condition of his health and life."

Life teaches us that there are many reasons that lead us to want to forget and intentionally put into practice actions (mental or behavioral) to "hide" or "expel" from our memory information, knowledge or specific memories. And it is that a world or a life without forgetfulness would not be desirable. The most convincing proof is found in the testimonies of people who, although it surprises us, cannot or do not know how to forget.

The Soviet neuropsychologist Alexander R. Luria had the opportunity to study for more than thirty years the exceptional gifts of memory of Solomon V. Shereshevsky, "a strange being", in the words of Luria himself, who, after failing in music and journalism, became a professional mnemonist, verifying then, strange as it may seem, that I didn't know how to forget.

Shereshevsky found himself in his work as a mnemonist with the terrible problem of not being able to forget the information of the previous sessions and found anguished that this information interfered and prevented him from remembering clearly that of the present moment. What to do to prevent those situations in which he felt flooded with useless memories?, What could he do to forget them?, How to learn to remove from his memory the images with the information he no longer needed? Shereshevsky saw the need to learn "the art of forgetting", for which he resorted to various mental strategies that led him to manipulate images, erase them, cover them mentally, separate himself from them ... but even so he could not get rid of them. (...)

Shereshevsky was desperate, he needed to forget in order to work. Not being able to forget became his biggest and "most painful" problem. Until one day, in a spontaneous way, he found the solution, whose nature was incomprehensible both to Luria and to him, who narrated his experience: "On April 23 I had three sessions in a row. I was physically tired and thinking about how to carry out the fourth session. I was afraid that the paintings of the previous three would appear to me. It was a terrible problem for me. Would he or would he not see the first frame? I'm afraid it will happen. I want it not to appear. And I thought: the painting no longer appears and I know the reason: I don't want it to appear! Therefore, if I do not want to, it does not appear... It's all about making him aware of it."

Surprisingly, that method worked and Luria argued that the forgetting had probably been produced by "its inhibition, completed by autosuggestion". The words of Shereshevsky himself are very revealing in this regard: "I felt liberated immediately. The certainty that I was safe from mistakes gave me greater security. He spoke fluently, I could afford to pause, I knew that, according to my wish, the image would not appear and I was perfectly fine."

José María Ruiz Vargas (Doña, Mencía, Córdoba, 1946) is Professor of Psychology of Memory at the Autonomous University of Madrid. This excerpt is a preview of Memory and Life. We are what we remember, from the publishing house Debate, which is published on June 1.

Sign up for the weekly Ideas newsletter here.