The afternoon boils in La Candelaria, in downtown Caracas, where a handful of people crowd to eat. They don't seem to mind the heat of the long black griddle of the cachapas stand (something like a cornmeal pancake), nor the dollar prices hanging on an ad for the dusty canopy of the cart. It is the current portrait of the proud Bolivarian Revolution.

Venezuela has entered the twenty-first century, no doubt. Gone are revolutionary political voluntarism (that which in his book on the twentieth century Alain Badiou compared to taking a beast by the horns) and its Cuban mirages.

The marks of his absence are felt throughout Caracas: Hugo Chávez's eyes no longer spy on the destiny of the country from above, nor does red stain bodies and minds as if it were a bloody uniform. And other emblematic projects of the Revolution, such as socialist areperas, Librerías del Sur and Bicentenario supplies, today give their space to more discreet and profitable businesses, such as restaurants, luxury hardware stores and especially still lifes (that is, imported delicatessen sales).

Venezuela went from being a Cuba with silver to a ruined Russia. Where a McDonald's closes, an import supermarket opens.

View of a meat store with its prices marked in dollars. Photo: EFE

The model of Gargantuan and irresponsible country that Chavismo built for a decade and a half now looks abandoned, half-built and half-demolished, because a sad alternative is already emerging from its bowels, like the creature of Alien.

This is the model of contemporary autocracies, whose oligarchies flourish under the blind weight of international sanctions, maintained by a client state. As a fellow writer put it during my visit to Caracas: "Venezuela went from being a Cuba with money, to a ruined Russia."

The metaphor is not fortuitous. In a imitation of perestroika, the government of Nicolás Maduro has proposed to make profitable the collapse of the country through a double doctrine of uncontrolled importation (what was called pax bodegónica, that is, to alleviate the shortage with products brought mostly from Miami) and capture of the spaces of the impoverished middle class, whose flight in recent years ceded the commercial terrain to new and more ruthless actors.

But the forms change and the spirit remains: where a McDonald's closes, an imported supermarket opens. All within the framework of a gradual de-ideologization of life, from which not even the vociferous harangues of the autocrat in Miraflores escape.

The elderly, the sick and almost 80% of the country's registered poor are coping on their own with the total collapse of the public scheme.

The Green Wave

The general mood is one of learned helplessness, of turning the page, of better talking about something else. Faith in the role of politics has been lost. And although there are many who observe the present with paradoxical relief, facing the memory of the so-called "years of hunger" between 2016 and 2018, it is difficult to know if things are really better.

Far from the slogan that swarms on social networks ("Venezuela fixed itself"), the immediate context of the country shows a brutal economic adjustment.

The elderly, the sick and almost 80% of the country's registered poor (ENCOVI 2022) face on their own the total collapse of the public scheme (hours without light, days without water, years without internet) and the micro-privatizations that are offered as the only solution: international medical insurance, purchase of water tanks, private satellite services.

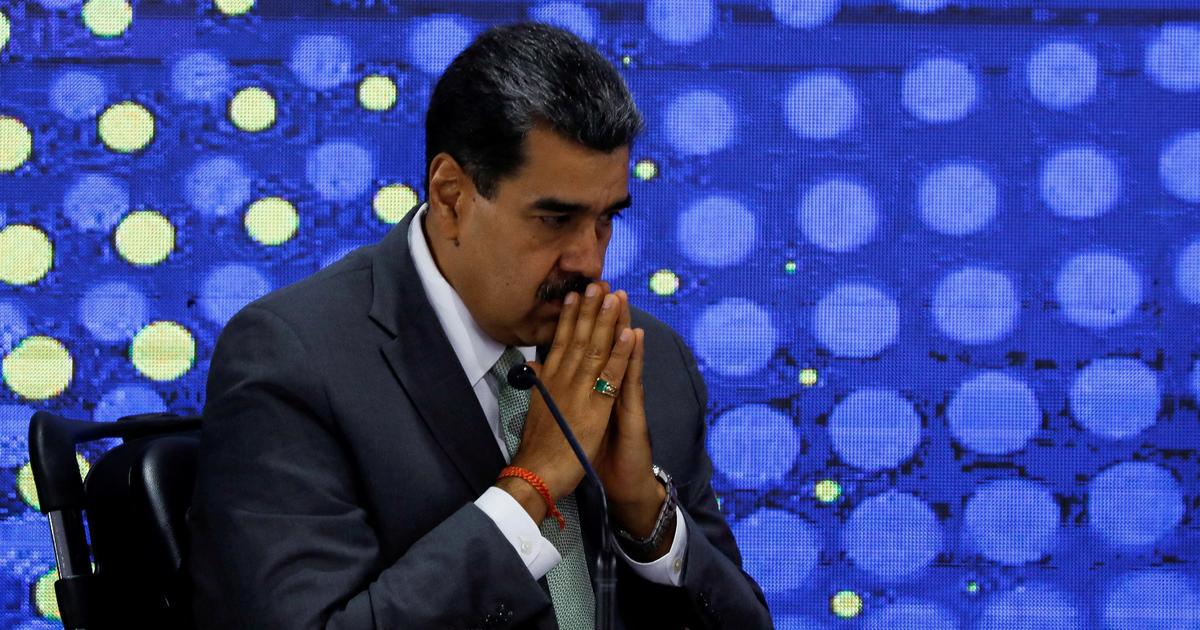

Nicolás Maduro and his wife Cilia Flores at the Labor Day celebrations in Caracas. Photo: AP

Even so, in his Labor Day speech, last May Day, Maduro asks to "resist" with a minimum wage of 5 dollars per month (130 Bolivars) to an interannual inflation that is around 500% (Venezuelan Observatory of Finance), and in exchange promises bonuses calculated in dollars: 20 for the "war bonus" and 40 for the food ticket, laughable figures in a country whose basic food basket was around 480 dollars in February (Cendas-FVM). The crowd, outraged in front of the podium, opposes, boos him. Nothing happens. The silver thread that linked the impoverished masses to the Revolution has become thinner than ever.

In everyday life, meanwhile, the pragmatism of the dollar prevails, circulating daily alongside the local currency of two different monetary cones, indistinguishable from each other to such an extent that people recognize the notes in progress by looking at the date of issue of each.

The old million-dollar bill is worth one; those of five hundred thousand, zero with fifty. The exchange control and its law of illicit exchange, which prohibited the purchase and sale of foreign currency, are a thing of the distant past: the official rate of the dollar, which oscillates 25 bolivars, is announced daily through the Central Bank and is replicated on posters and blackboards next to the cash registers of supermarkets and bakeries.

All products are offered in dollars, although a patriotic modesty leads to hide that name with euphemisms such as "reference", "ref." or the sign that seems appropriate. The Bolivar, in its third reincarnation and with fourteen zeros less than it had in 2000, serves only as a substitute for the cents of the dollar.

Demonstration for better wages, in Caracas (Venezuela). It was in January of this year. Photo: EFE

Bank cards offer a few bolivars on loan, that is, a trip by metro or bus. The same goes for traditional, medical and funeral insurance, which covers at most a few hundred dollars.

Vintage country

In this context, consumption is governed by rather suspect rules. In the same street you can see desolate businesses and the announcement of new ventures, despite the fact that credit is almost non-existent in Venezuela: bank cards offer a few bolivars on loan, that is, a trip by metro or bus. The same goes for traditional, medical and funeral insurance, which covers at most a few hundred dollars.

The price dynamics, however, still wounded by past hyperinflationary spirals – the peak was in 2018 with 130,060% year-on-year (IMF-WB) – is more in line with the precepts of the free market of certain flamboyant "libertarians" that swarm in social networks than with the old designs of the developmentalism of the twentieth century.

Perhaps that is why the nineteenth-century eagerness of Chavismo, its jingoistic ruralism and its determination to refound the independence process have become a kind of agonizing trademark. His faded puppets in murals and avenues, his solemn busts in front of a recent baseball stadium, all this already emanates the nostalgic whiff of vintage, of the obsolete and obsolete.

In the shadows, however, the old trenches of our civil war by surrender make peace: the defenders of the public and those of the private shake hands, while the militancy of both sides pretends to be distracted.

Blatant privatizations and discreet state interventions are possible in twenty-first century Venezuela, as long as the bugle of the parties is silenced and the new owners of the country are not questioned.

That is what the government itself will take care of when it suits it, because as the saying goes, among firefighters they do not step on the hose, and the new Creole oligarchy, born in the heat of the revolutionary anvil, has no time to lose: a country hungry for consumption lines up in front of its cash register and the money in its anxious hands begins to dwindle again.

The author

Gabriel Payares (40) has a degree in Letters, a master's degree in Latin American Literature and Creative Writing.

Born in London where his parents were doing their doctorates, he grew up in Caracas, where he lived until he emigrated to Buenos Aires in 2014.

Winner of several literary awards, author of the books Cuando bajaron las aguas and Hotel, he published in Argentina Lo irreparable (Corregidor), a exquisite volume of stories.

See also