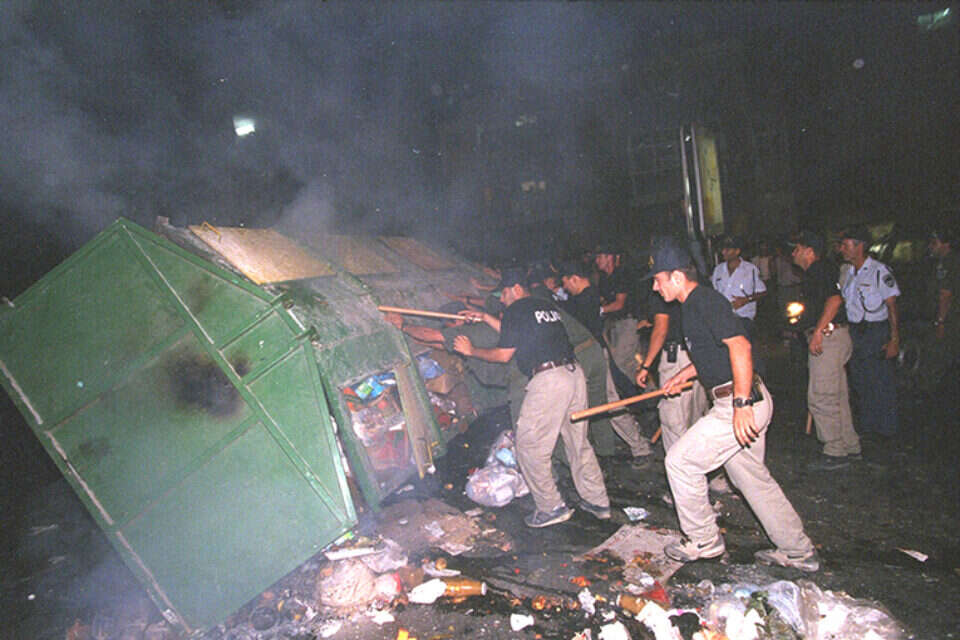

The Bar-Ilan Road riots in Jerusalem three decades ago polarized Israeli society and occupied it for years. Thousands of ultra-Orthodox Jews who demanded that the road be closed on Saturdays demonstrated there week after week, often with severe violence. They were confronted by groups of secular Jews from all over the country, who deliberately drove along the road on Shabbat, and even beat the ultra-Orthodox. The High Court of Justice took up the issue after Meretz and Labor members petitioned against the intention of then-Transportation Minister Rabbi Yitzhak Levy of the National Religious Party, to close the street for a few hours every Shabbat. They demanded a complete opening of it.

But then a great wonder occurred: the High Court, in an almost unprecedented manner, decided not to rule on the dispute. When we return today to the same decision made by then-Supreme Court President Aharon Barak, the jaw drops in astonishment. After all, this is someone who believed that "there is no action to which the law does not apply," but he actually instructed the government to appoint a balanced public committee to recommend to judges how to act.

Imagine the High Court ordering a referendum, or establishing a "public committee," as Barak did at Bar-Ilan. How wise and humble were there then, and how far over the years Barak and the High Court of Justice have distanced themselves from that wisdom, and to what degrees their arrogance has risen

Barak then used terminology that fits like a glove into the events of the legal reform. "In the public discourse in Israel," he explained, "Bar-Ilan Street has ceased to be just a street. It has become a social concept. It reflects a deep political divide between ultra-Orthodox and secular Jews. This is not just a dispute over freedom of movement... Saturday on Bar-Ilan Street. This is mainly a serious dispute over the relationship between religion and state in Israel; A fierce dispute over Israel's character as a Jewish or democratic state... This dispute was brought before the court, and we decided to transfer it to the public for decision."

Aaron Barak. Right decision, photo: Michelle Dot Com

The person who rescued this rare ruling of the High Court of Justice from the depths of time is the historian, educator and teacher Zvi Tzameret, who for decades enlisted himself in the task of bringing the people closer together, and was even appointed by the then Minister of Transport to head the same public committee. Tzameret passed away a few months ago, but before his death he managed to complete his autobiography (published by Yedioth Books). Some of the pages there deal with this forgotten and relevant affair.

Travel to Kiddush on Shabbat

Imagine the High Court of Justice, which decides following petitions on the issue of recruiting yeshiva students or on the issue of reform – not to decide on these polarizing issues, and to transfer them to "public decision." Imagine Esther Hayut and her colleagues instructing them to hold a referendum, or to establish a "balanced public committee," as Barak did in the Bar-Ilan affair. How wise, modest and humble were Barak's decision at the time, and how far over the years Barak and the High Court of Justice have distanced themselves from that wisdom, and to what degrees their arrogance has soared.

The High Court of Justice demanded that the Tzameret Committee not be satisfied with the question of whether or not to close Bar-Ilan Street to traffic on Saturdays. He also instructed her to deal with "the expected social dynamics [throughout the country] and its impact on secular-religious relations in Jerusalem... (and) access long-term solutions."

The High Court of Justice. One can only imagine other decisions, photo: Oren Ben Hakon

Tzameret and his colleagues consulted with dozens of public figures, rabbis and academic experts. They proposed a detailed package of measures to soften the secular-ultra-Orthodox conflict, and regarding the road, they recommended closing it on Saturdays, but only during prayer hours, while operating three public taxi lines in the city. Neither side came out with all their lust in their hands. The committee's decisions were carrots and sticks for both the ultra-Orthodox and secular publics.

Tzameret reveals in his book that the person who proposed the compromise was Rabbi Shar Yashuv Cohen, the representative of the national-religious public on the committee, and the person who gave it the majority was another representative of the national-religious public, Rabbi Prof. Daniel Sperber. The High Court of Justice adopted the recommendations by a majority of four to three, and there too the only religious judge on the panel, Zvi Tal, ruled in their favor.

Behind the scenes, the Sephardic Chief Rabbi at the time, Rabbi Eliyahu Bakshi Doron, gave impetus to the compromise, urging the leadership not to surrender to ultra-Orthodox extremists, and even clarified: "I ask that those who travel to their mother on Friday nights to make Kiddush continue to do so." An equally significant conversation took place after the decision on the compromise with the spiritual leader of Shas, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, who blessed the "peace of the house that was achieved," despite the desecration of the Sabbath of driving on the road that involved it. Rabbi Yosef, Tzameret relates, "said things I will never forget: 'There is no greater blasphemy than throwing stones on Shabbat. There is no greater danger to the Torah than separation among the people of Israel, and there is no greater harm on Shabbat than violence on Shabbat.'"

"Don't force a core"

If only all parties to today's disagreement were to embrace the recognition that the greatest danger is the separation of the Jewish people, their path to compromise would be easier. Tzameret almost found himself called to the flag to compromise and mediate even in the difficult rift over the legal reform, but he died about a month after it was introduced. In his book, he shares with us his sober assessment of the chances of reaching understandings with the ultra-Orthodox, whom the leaders of the protest against the reform have now marked as another goal.

"... The more I know them," he wrote, "the more optimistic I am. At the same time, it is clear to me that integrating them is not easy, because they want first and foremost to preserve their identity." Tzameret believed that the Haredim would change in terms of employment: "... More ultra-Orthodox men, not just women, will be forced to go out to work and help support their household."

He estimated that change would also come in the field of education: "I oppose forcing the ultra-Orthodox to study core studies such as civics, the Bible or history, but I believe in the possibility of persuading them to voluntarily study English, mathematics and computers, subjects that will determine the degree of their integration into the future economy."

Not surprisingly, Tzameret defined the issue of haredi recruitment into the IDF as "one of the most complex problems weighing on the Israeli public," but in light of his experience, he did not believe that a court could solve the problem: "In my opinion, it will only exacerbate it." In his book, he talks about compromise outlines that the Haredim might be able to agree to, such as "establishing separate battalions of Haredim to serve in the Home Front Command," and is convinced: "We will all have to shake off our sectoral bubble and recognize the fact that we are one Jewish-Israeli family and that our fate is one."

Tzameret's latest book is a documentation of a wonderful life journey, at the end of which the connection that is so necessary today between the Jew and the Israeli was created. It teaches that we must not give up on creating a better and more connecting future. At first, Tzameret confesses, he thought that the name "Zvi" given to him by his parents was an exile name: "I preferred 'Zvika'... I thought that a great ocean separated me from the old Jewish world..."

Only his studies of Judaism and history gave him the understanding that there is no contradiction between the old "Zvi" and the new "Zvika," and between the Jew and the Zionist. His final journey through the stations of his life, "From the Land of the Zvika to the Land of the Deer" (the title of his book), provides some recipes for compromises that are so necessary in the age of polarization and radicalization in which we live today. The people of the President's House should read them.

Wrong? We'll fix it! If you find a mistake in the article, please share with us

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/5CHLJIJ7345AINNALD43FNAAE4.jpg)